Référence électronique

Vorobieva E., Rumyantseva P., (2020), « Body and power: does contemporary russian tattooing retain its protest potencial? », La Peaulogie 8, mis en ligne le 07 mars 2022, [En ligne] URL : https://lapeaulogie.fr/russian-protest-tattoing

Body and power: does contemporary russian tattooing retain its protest potencial? The dynamics of the development of the protest tattooing in a prison and in a “big” societies of the Soviet Union and Russion Federation.

-

Description

Ekaterina VOROBIEVA

Ph.D. in Sociology, Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration under the President of the Russian Federation, Liberal Arts Faculty, lecturer.Polina RUMYANTSEVA

3rd year bachelor, Faculty of Liberal Arts of Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration under the President of the Russian Federation.Résumé

L’article se concentre sur les dynamiques de la mise en avant de protestations à travers le tatouage, dans une prison russe, dans les « grandes » sociétés de l’Union Soviétique (URSS) et de la Fédération de Russie aux XXème et XXIème siècles. Il est démontré que la fonction de protestation du tatouage est étroitement liée à la situation politique, économique et culturelle d’un pays. Dans les prisons de l’URSS, le tatouage exposant une protestation est apparu à la fin des années 1930, les objets de la manifestation étant Karl Marx, le communisme, le PCUS, les chefs de parti de Lénine à Staline. Dans la « grande » société de l’URSS, ce type de tatouage apparaît peu de temps avant l’effondrement de l’URSS et est étroitement associé à la protestation contre le désespoir du système communiste dans le pays. Après l’effondrement de l’URSS en 1991, dans les prisons et au sein de la « grande » société de la Fédération de Russie, le motif de protestation diminue progressivement dans les tatouages. Ces derniers se commercialisent, deviennent à la mode et s’intègrent à la culture du marché de masse. Cependant, certains passionnés de tatouage continuent toujours à donner un sens de protestation à leurs tatouages.

Mots-clés

Tatouage, Tatouage contemporain comme motif de protestation, Tatouages de prisons russes, Tatouages dans la «grande» société russe

Abstract

The article focuses on the dynamics of the protest motive in tattooing in a Russian prison and in a « big » societies of the USSR and the Russian Federation in 20th and 21th centuries. It is shown that the protest function of tattooing is closely related to the political, economic and cultural situation in the country. In the Soviet Union, a protest motive in prison tattooing arose by the end of 1930s. Objects of the protest were Karl Marx, communism, the CPSU, party leaders from Lenin to Yeltsin. In the “Soviet big” society of the USSR, tattooing appears shortly before the collapse of the USSR and is closely associated with a protest against the hopelessness of the communist system in the country. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, in the Russian Federation the protest motive in prison tattooing and tattooing in a “big” society is gradually decreasing, tattooing is commercialized, becomes fashionable and fits into the culture of the mass market. However, it does not disappear completely, and some tattoo enthusiasts continue to put a protest meaning into their tattoos.

Keywords

Tattooing, Protest motive of contemporary tattooing, Russian prison tattoos, Tattoos in the Russian “big” society

The study of contemporary tattooing is problematic without identifying the stages of its development, since from the moment of its penetration into the European and North American continents at the end of the 18th century, the social composition of tattoo enthusiasts adherents, content of tattoo images and meanings which tattoo enthusiasts put into their bodily practice change. A number of North American specialists in the history of tattooing (Robert Brain, 1979, Victoria Ebin, 1979, Arnold Rubin, 1988, Jane Caplan, 2000, Steve Gilbert, 2000) offer a systematic periodization of the process. Six main stages of the tattooing development are distinguished: (1) the colonist/pioneer era (1760‑1870); (2) the circus/carnival era (1880‑1920); (3) the working‑class era (1920‑1950); (4) the rebel era (1950‑1970); (5) the new‑age era (1970‑1990); (6) and the supermarket era (from 1990 to the present). A generalized description of the stages is presented in the study of Michael Atkinson. Despite the proposed periodization of tattooing focuses on the development of the process in the North America, it, according to Margo DeMello (2000), the largest American historian of tattooing, reasonably reflects the nature of the development of tattooing on the European continent, and thus can be considered universal for the West as a whole.

These stages are not fully applicable to the history of tattooing in Russia[1]. In Russian Empire, the time frame of the “the colonist/pioneer era” shifts towards the 19th century; there was no “the working‑class era” neither in pre‑revolutionary (until February 1917) nor in post‑revolutionary Russia. “The rebel era”, which Atkinson associates with the heyday of prison protest tattooing in the West, in the USSR springs up in a prison subculture formed by 1930th, and there are two differences. Firstly, “the rebel era” in prison tattooing had not come to an end by 1970th and even with the USSR collapse in 1991. Secondly, it can be directly related to the emergence of the youth countercultures in a “big” society[2] of the USSR in 1980s (new wavers, punks, fans of the metal music, rockers, bikers, and tattooists) with their active protest against the Soviet political system that imposed significant restrictions on human rights and freedoms. In this regard, “the new‑age era” emerges in the late USSR in parallel with the “the rebel era” and ‑ as the prison protest tattooing ‑ also has protest roots. As for the stage of the “supermarket era” which, according to Atkinson, replaced “the new‑age era” in the West in 1990, Russian realities also have some differences at this point. Foremost, due to the later establishment of the capitalist system and the market economy in post‑socialist Russia compared to the West, the first legal commercial tattoo parlor opened in the Russian Federation (hereinafter RF) in Moscow only in 1995, and the spread of tattoo industry throughout RF took place at the end of the 1990s ‑ 2000s. On the other hand, due to the development of a market economy in the 1990s and regular commercialization of many activities, “the supermarket era”, with its ideology of prestigious consumption, by the end of 1990s gradually split the tattoo community into two camps. Representatives of the first group sought to integrate tattoo culture into art and fashion domains within the dominant culture. Realizing that tattoos still challenge the appearance norms and stereotypes of bodily beauty that dominated in a public mind[3], they tried not to advertise their tattoo practices, placing tattoo images on those parts of the body that could have been hidden under clothing. Representatives of the second group sought to maintain the subcultural boundaries of tattoo community and the value of defiance, placing tattoos on visible parts of the body: hands, neck, face. Thus, two ideologies were simultaneously established in tattoo culture: the ideology of prestigious consumption and the ideology of confrontation.

When focusing on the protest motive in tattooing, we will firstly suggest an explanatory model of a protest origins of contemporary tattooing, and then relying on an explanatory model will analyze the prison tattooing, and tattooing in “big” societies of the late USSR (closed society) and the Russian Federation (open society[4]).

Explanatory model of protest tattooing

When speaking of the protest aspects of contemporary tattooing, we should clearly realize that at all times and in all societies, human behavior, including bodily self‑presentation, has always been governed by society and its institutions. And that culture of any society, producing a spectrum of norms in all spheres of human life, always imposed restrictions on the free self‑determination of a person in accordance with his own ideas and values, thereby demonstrating its power over the individual. And as Michel Foucault remarked at one time, wherever there is a power, there is certainly a resistance…

Of course, Foucault’ statement is not mainly applicable to societies of modernity and postmodernity, ‑ in traditional, “primitive” societies, concepts of “personality”, “Me”, simply did not exist, and the power of custom was not questioned, since collective self‑awareness prevailed. Even if isolated cases of disobedience took place and certain norms were violated, they were brutally suppressed[5]. In two main totalitarian states of the 20th century, Nazi and communist, we see a similar picture of violence, but the mass opposition is gradually growing into the social space. As for modern and postmodern societies, which proclaimed the values of personal independence and individuality, they appear to be not as democratic as it is declared. Under the conditions of the capitalist system, social institutions perform the same function of overseeing and regulating human behavior, including bodily behavior, as a custom in premodern societies did.

As Mary Douglas argues, institutions govern not only human behavior, but above all, they govern human thinking by imposing their own conceptual frameworks. Therefore, identifying how institutions exercise control over our consciousness is the first step in resistance to these narratives in order to gain intellectual independence, and then freedom of social behavior. In this regard, if we want to explain modern tattooing as an action of resistance, we must first of all analyze how tattoo enthusiasts assess the power of the narratives of social institutions and what narratives they form themselves, which we assume determine their protest tattoo practices. We will demonstrate how correct our hypothesis is, later in the analysis of our empirical research conducted, and now we should present those specific cultural narratives that function in modern societies and seek to govern human behavior.

When we talk about the management of human behavior in modern societies that can trigger a backlash, we must consider several factors. First, despite the secularization of modern societies, more than 2,000 years of Christianity on the Eurasian continent did not pass without a trace, and Christian maxims continue functioning in the public consciousness as culture universals[6]. These universals have an impact not only on the spiritual life of modern man, but also on his bodily behavior. Here we meet the main postulate: according to the formula of Apostle Paul, the human body “is the temple of the Holy Spirit living in you which you have from God.”[7] Consequently, the body is not a property of its owner and from this follows the maxim of bodily purity, according to which any bodily modification is declared a sin. Orthodoxy in this case pursues a tougher policy in comparison with Catholicism and Protestantism, and in the RF is not so rare that tattooed people are expelled from an Orthodox church[8]. Thus, the Russian Orthodox Church acts as one of the main social institutions that ban tattoo practices, and thus acts as one of the main institutions which tattoo enthusiasts may reject.

Second, modern capitalism gave rise to the type of culture that, according to Max Horkheimer and Teodor Adorno, is a commercial industry with the goal of engaging individuals in the consumption process and subordinating them to their purposes. Culture industry seeks to quantify and typify the whole variety of social and subordinate the individual personality in all its manifestations to its control. Autonomy of personality, according to Adorno and Horkheimer (2001, 100), personal identity, in the modern world is problematic: the whole world is passed through the filter of the cultural industry. Culture industry operates via institutions of fashion and beauty, which form the standards of appearance that consumers must meet. Fashionable bodily modifications are being imposed on consumers through advertisements and articles in glamorous magazines: semipermanent and permanent cosmetic and surgical procedures like botox and hyaluron injections, circular facelift, reshaping of the nose or lips, breast implants, liposuction, and other invasive surgeries. Tattooing of the last decade, both in the West and in the Russian Federation, is trying to integrate into this global beauty industry, but this integration cannot be called successful. Since one of the main values of modern tattoo culture is emphasizing individuality, its ideology is difficult to integrate into the controlled production process of standardized images that the beauty industry imposes on consumers. Thus, tattoo enthusiasts place themselves outside the dominant culture, challenging its norms of bodily representation.

Third, if a tattooed person opposes his bodily appearance to the cultural norms of corporeality prevailing in society, it is logical to assume that he has a special inclination towards non‑conformism, independence and inner freedom, which allow him to critically assess other cultural narratives and produce his own patterns. These narratives are associated not only with the imposed standards of corporeality, but also with the lifestyles promoted by the culture industry, which are also a part of the aesthetics of modern societies. According to Dmitry Ivanov, a prominent Russian researcher in political sociology, an aesthetic form and cultural logic of today’s capitalism finds its justification in the ideology of glamour. Ivanov writes: “The essence of glamour is luxury, the meaning of which is not in expensive items per se, but in exclusive consumption that goes beyond functionality, therefore, luxury is equally represented, for example, by a mobile phone inlaid with precious stones (which can cost ten times more than a regular mobile phone, but it does not provide ten times better communication at all), a first‑class air passenger (who travels the same distance and at the same speed as an economy‑class passenger, costs twice as much), or advice from a business consultant (containing what taught in any business school, but costing several times more)” (Ivanov, 2015, 6). If the total power of the glamour ideology is realized and evaluated critically, it shapes the process of formation the individuals’ conscious need for autonomy, reflective and controlled construction of an identity that does not fall under any of the systemically sanctioned patterns. This leads to lifestyles that confront and challenge dominant consumerism and corporate market power (Kozinets, 2002; Murray Ozanne, 1991). In part, this can also explain the increased interest in tattooing as one of the elements of an alternative practice of individuals’ constructing identities through unconventional bodily representation. Thus, tattooing can be understood as a manifestation of freedom of thinking and action.

Fourth. So far, we spoke of the power of social institutions that govern human behavior. However, power is associated not only with the normativeness of social institutions. According to Michel Foucault, power does not have a strict centralization and is dispersed throughout the whole social body. It is not some kind of institution or structure, not some a specific power that someone would be endowed with: “it is the name given to the complicated strategic situation in a concrete society” (Foucault, 1978, 193).

Thus, we are talking about “bio‑politics”, about the political background of the construction of bodily behavior, and this point will become central to subsequent sociological theories of “gender bodies” that proclaimed that “the private” was actually “the political”.

As a political reaction of individuals to power technologies that determine their behavior and subordinate them to specific goals or forces through objectification of the subject, Foucault proposes a strategy of “technologies of the self, which permit individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality” (Foucault, 1988, 18). Since “hermeneutics of the subject”, according to Foucault, is the knowledge of the soul, mind and body as a single complex, working with the body is an important part of “knowing oneself”, the tradition of which, as Foucault showed, dates back to ancient Greece. It is through such creativity that a man’s power is revealed. Developing Foucault‘ concept of the “technology of the self”, Nick Crossley suggested the concept of “reflexive bodily techniques” (Crossley, 2001, 2006), which he divides into three zones: primary, intermediate and marginal. Crossley locates tattooing between the intermediate and marginal zones. The latter includes extreme bodily practices that can act as a strategy for the resistance social norms (Crossley, 2005, 26). As Mary Koshut claims, “since a human body is an object of manipulations the act of tattooing allows the possibility of owning the body, in addition to living within it” (Kosut, 2015, 33).

Summing up, we can argue that the protest aspect of tattooing is inspired by the power of influential social institutions and of social as such that seek to control human behavior, and the tattoo enthusiasts’ symmetrical response to an attempt to subjugate them is to cultivate unconventional bodily practice that leades to creative identity formation and self‑knowledge.

Protest tattooing in a russian prison

Systematic studies of prison tattooing in pre‑revolutionary Russia have not been conducted. The first professional study of prisoners’ tattoos in the USSR was carryed out by Michael Gernet in 1924‑1925. Gernet examined tattooes of 197 prisoners, and interviewed 37 of them. His conclusion was the following: “Often religious and indiscreet drawings coexist on the same body side by side. […] On the other hand, tattoos such as, for example, very common anchors and hearts, burning with flame or pierced by arrows and daggers, either say nothing, or they indicate only minute moods, temporary hobbies”[9]. Gernet pointed out that prisoners themselves often explained their tattooing in prison with boredom or imitation, never with resistance, and we can find no tattoo images with protest plots in his album.

How can we explain the fact that in 1920‑1930s prison tattoos were in no way connected with the protest theme and protest tattooing appeared in the USSR only at the end of the 1930s?

First and the main. Protest prison tattoos could have arised only within the protest prison subculture, which appeared to be a symmetrical response to the tightening of the entire penitentiary system of the USSR within the framework of the “Great Terror”[10] initiated by Joseph Stalin in 1937‑1938[11].

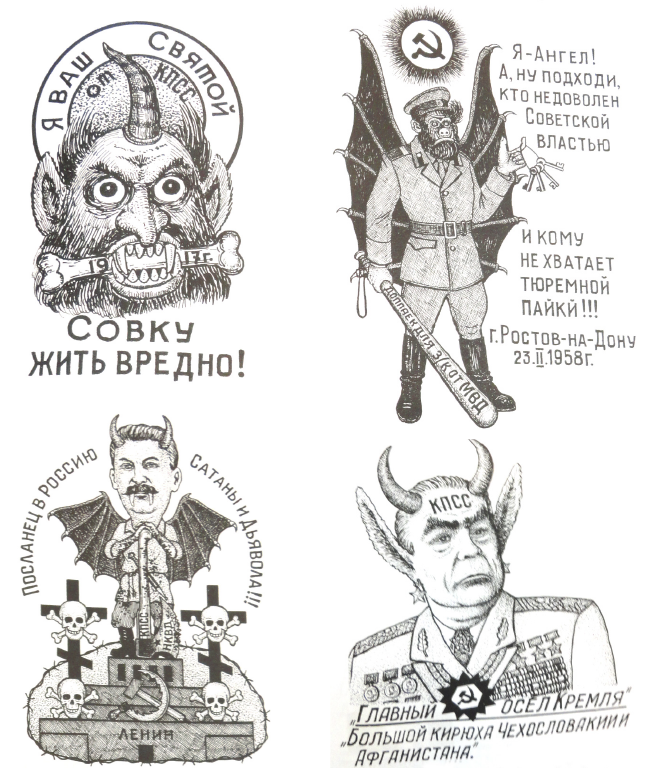

Fig. 1.

Top left image (60s of the 20th century): on the halo above the devil’s head it is written “I am your Saint from the Communist Party”, and under the head – It’s harmful to live for a scoop!” (A “scoop” is the slang name of the Soviet Union).

Top right image (1958): the inscription is: “I’m an Angel! Come on, whoever is dissatisfied with the Soviet regime and who lacks a prison ration!!! Rostov‑on‑Don.” On the baton there is the inscription: “extra rations for the indigenous inhabitants of the prison from the Ministry of Internal Affairs.”

Bottom left image (1991): the inscription around the head of Stalin standing on the Lenin’s mausoleum says: “Envoy to Russia of Satan and the devil.”

Bottom right image (1970s) the inscription sayes “The main donkey of the Kremlin. Great bibber of Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan.”

Images are taken from: Baldayev D.S. Tatuirovki zaklyuchennykh. (Tattoos of Prisoners: Album. St. Petersburg: Limbus Press, 2001). (In Russian).

As Andrei Oleinik, a well‑known researcher in the Russian prison subculture, argues, a prison and a “big” society are in a state of congruence. “They are congruent not because the prison world is derived from the surrounding society, but because they are both derived from the same model of power relations” (Oleinik, 2001, 36). In this regard, the emergence of a prison subculture with a strict hierarchy of thieves’ statuses, norms of behavior, jargon, tattoos “by rank” and a system of severe sanctions which criminals imposed on those who violated established criminal norms coincided in time with the tightening of the repressive regime in the “big” society of the USSR from the late 1930s. A distinctive feature of the prison subculture as a “total institution” was solidarity within the criminal community and the hostility of its members to everything beyond. Since the repressive Soviet state was declared the main enemy, which limited the physical freedom of prisoners, many of whom were convicted under political articles, the main objects prison tattooing challenged were the communist ideology and the totalitarian regime of the USSR, which were embodied by its creators and guides: Karl Marx, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and its political leaders – from Lenin to Yeltsin (Fig. 1: Top left image, bottom left and right images). Since by 1950s tattoos in prisons were officially banned by the prison authorities and if they were found, they were forcibly cut off with the skin, their application itself was a kind of challenge to the prison administration which appeared to be the next object of confrontation (Fig. 1: Top right image).

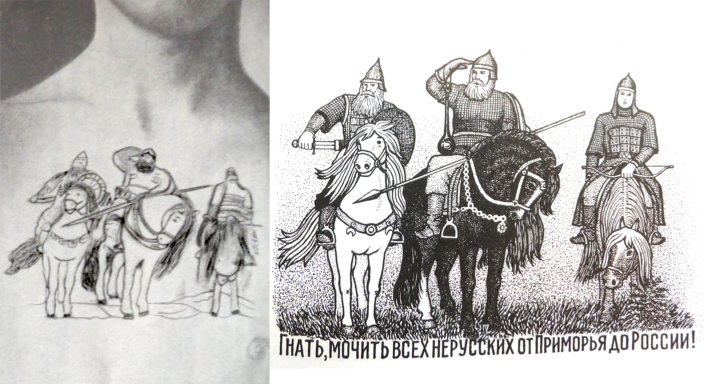

Second. Since most of the Union republics of the USSR were included in its composition mainly by violent methods, in most of them this gave an impetus to the development of nationalism, which divided society by nationality: “ours” and “aliens”. This explains the fact that the protest prison tattoo was also aimed at abandoning other nationalities: Ukrainians, Armenians, Uzbeks, etc. (Fig. 2).

The dynamics of prison tattoos from simple amusement to the ideological protest are especially visible when comparing two identical plots, one of which was tattooed in 1920th and the other – in 1951 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Left image (the 1920th). We see just a reproduction of Vasiliy Vasnetsov’s famous painting “Three Bogatyrs”. Three Bogatyrs are the heroes in Russian folklore.

Right image (1951), The Image is taken from: Baldayev D.S. Tatuirovki zaklyuchennykh (Tattoos of Prisoners: Album. St. Petersburg: Limbus Press, 2001). (In Russian). We see the same image, but the inscription notifies: “TO Drive out, TO rot all non‑Russians from littoral OF russian FAR EAST to Russia!” The Image is taken from: Gernet M.N. Tatuirovka zaklyuchonnykh gor. Moskvy. (Tattoo of prisoners in Moscow // The Underworld of Moscow: a collection of articles: A.M. Aronovich, N.N. Gedeonov, M.N. Gernet [et al.]: With photographs, figures and diagrams / edited and with a foreword by prof. M.N. Gernet. Moscow, Law and life, 1924.). (In Russian).

Images are taken from: Baldayev D.S. Tatuirovki zaklyuchennykh. (Tattoos of Prisoners: Album. St. Petersburg: Limbus Press, 2001). (In Russian).

Top left image (60s of the 20th century): on the halo above the devil’s head it is written “I am your Saint from the Communist Party”, and under the head – It’s harmful to live for a scoop!” (A “scoop” is the slang name of the Soviet Union).

And the third, psychological explanation. Since by 1940‑1950s tattoos in prisons were officially banned by the prison authorities and if they were found, they were forcibly cut off with the skin, their application itself was a kind of challenge to the prison administration. According to Michel Atkinson, who analyzed prison tattoos in western prisons, the bodies of the criminals could not have been physically released, literally, due to the fact that they were imprisoned in the walls of penitentiary institutions, “but they could receive a symbolic release through tattoos” (Atkinson, 2003). This symbolic release can be interpreted as a kind of psychological compensation for bodily lack of freedom through the freedom of personal manipulation of one’s own body, even if it is fraught with hazard of punishment. In the case we meet tattoo images addressed to prison administration (Fig. 1, Top right image).

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991 and the liberalization of the political regime in the RF, prison conditions have softened. Accordingly, protest plots of prison tattoos have become rarer. A small number of sociological and socio‑anthropological studies of prison tattooing in the RF of 1990‑2000th [12], however, protest tattooing was either not emphasized at all, or was considered along with other types of tattooing without any conceptualization; the studies themselves were purely descriptive. Thus, prison protest tattooing 1990‑2000th fell out of the research field, and we have a big gap in this area.

The main source of information about the prison subculture of the 2000s is the research of Andrei Oleinik we mentioned earlier[13], a few television stories and forums of former prisoners who were released in the 2000s. The main conclusion that can be drawn from these sources is that by the early 2000s a prison subculture experienced the influence of a market economy and prison tattooing was commercialized: “out of rank” tattoos were applied for money. During Putin’s rule, the protest motive waned – mainly in the “red belt”[14] prisons. The commercialization of protest motives in prison tattoos reaches its climax in a recent project by O. Navalny, who made drawing of protest tattoos on skin and clothes a business project that has got popular both in Russia and in the West.

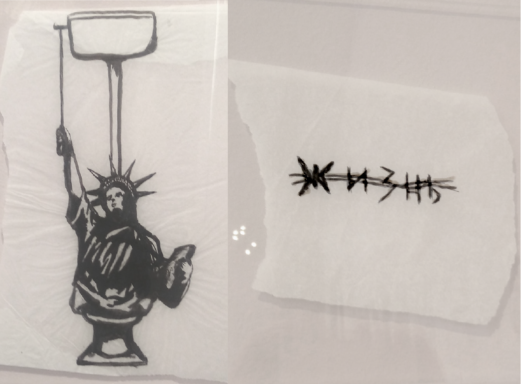

On Fig. 3, the left image can be interpreted as a ascertainig of the destruction of civil liberties in Putin’s Russia, and the right image ‑ as a symbol of the fact that the hole life in a society of the Russian Federation is shrouded in barbed wire.

However, the assertion that modern Russian protest tattooing in peasons has completely turned into a farce would be a mistake. In prisons of the “black belt” it still exists, although the tone of the images has softened. Due to the liberalization of the political regime in 1990‑2000s and a significant reduction in prisoners convicted of political articles, tattoos with the images of political leaders are less common and are not as sarcastic, mocking in nature as in the USSR. But nationalist tattoos, calling for the expulsion or destruction of the alians and Gentiles, are much more common than in 1930‑1990s.

Fig 3. Sketches of prison tattoos by Oleg Navalny. Tattoos from Russian Prison.

URL: https://www.instagram.com/got_chif/?utm_source=ig_embed (date of the application 20.11.2019).

Left image: The American Statue of Liberty flushes itself down the toilet.

Right image: the inscription “life” is crossed out by barbed wire. Photo by E. Vorobieva.Protest tattooing in “big” societies of the ussr and the russian federation

The source of our analysis of the protest tattooing in the “big” society of the late USSR (1985‑1991) is 20 unstructured interviews which have been taken in the mid‑1980s in Moscow and Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) by Michael Buster, one of the first tattooists in late USSR, from representatives of tattoo counterculture of that period[15]. These representatives of the first generation of tattooists were 18‑25 y.o. and came either from the families of workers, or from the families of the creative intelligentsia (writers, artists, musicians, etc.) Some of them had a higher education, some dropped out, some were limited to school education and had no desire to enter the universities. None of them had a special art education. The clients of tattooists were predominantly representatives of the countercultures that arose during this period and belonged to the same social groups as the tattoo artists did.

The sources of our analysis of the protest tattooing in the “big” society of the Russian Federation (2010‑2019) are 40 semi‑structured in‑depth interviews with the second generation of tattoo artists and tattoo clients 18‑40 y.o.conducted by Ekaterina Vorobieva in 2010‑2012 (hereinafter Research 1), and 38 semi‑structured in‑depth interviews with the third generation of tattoo artists and tattoo clients 18‑35 y.o. conducted by Ekaterina Vorobieva and Polina Roumyantseva in 2019 (hereinafter Research 2). In both researches, the panel was formed by the “typical representative” method: it included tattooists who worked in well‑known tattoo parlors or worked with clients at home, and each tattooist recommended two of his clients with the most expressive tattoos he had done. The social background of the second and the third generations of tattooists was the same as that of the first one. But in the second generation of tattoo artists, about a third had a secondary or higher art education, and in the third generation, more than a half graduated from art universities. In both studies, three social strata were represented in the sample of tattoo clients: college and university students, mid‑level specialists, and top managers or owners of their own businesses. Both series of interviews were conducted according to the same guide. The Research 1 aimed to get the most complete picture of what the tattoo culture of this period was, what were the main reasons for joining it, what were the subjective motives for tattooing and how the tattoo biographies of tattooists and tattoo collectors developed. The client interview guide consisted of 8 thematic blocks, with tattoo artists ‑ of 10. The same was the Research 2. Both researches identified 16 subjective motives for tattooing: imitation; protest; shocking; psychological relaxation; search for a circle of friends; fixing belonging to a group; aesthetic motive; psychological defense; improving self‑esteem; psychological intimidation; demonstration of social status; fixation of affection; overcoming yourself via overcoming pain; fixing significant events; self‑expression / self‑knowledge; and professional implementation (for tattoo artists). Since the article concentrates on the protest tattooing, we will limit ourselves to analyzing the protest tattooing motive and the corresponding tattoos.

Protest tattooing in “big” society of the USSR

As Michael Buster argues, tattooing in the “big” Soviet society of the USSR of the mid‑1980s ideologically closely came into contact with the countercultures of new wavers, punks, metal music fans, rockers, break dancers and bikers that arose during that period. Adherents of tattoo counterculture, on the one hand, shared a common ideology of counterculture protest against the imposed communist ideology and the restriction of civil liberties: what people can openly talk about, what kind of life they should lead, what music to listen to, what clothes to wear, etc. On the one hand, they opposed their personal freedom and independence to the total regulation of all spheres of life, demonstrating with their way of life and outward appearance a protest against the “closed” society of the USSR with its main enemies: the capitalist West in general and Western culture in particular, and the imperatives, what a Soviet person should be and look like. They refused working for the state, and aimed money as black marketeers who sold Western clothes, Western music CDs and other Western goods illegally imported into the USSR. As Buster notes, in this way a person removed himself from society, deliberately choosing the status of a marginal. Representatives of countercultures closely communicated with each other, avoiding “strangers”, the names of tattoo artists and their addresses were kept in secret, access to a tattoo master was possible only on the recommendation. On the other hand, tattoo counterculture adherents sought to contrast their practice with prison tattoo culture with its special symbolism (tattoos of stars of “thieves in law”, rings indicating the “rank” of a criminal, etc.). Two main motivations for tattooing took place: a protest against the Soviet state and ist ideology of a “closed” society and fixing belonging to a counterculture group.

Protest tattooing in “big” society of the Russian Federation

The late USSR, since its collapce of the communist ideology and “planned economy” by 1991 terned to he West experience, and was replaced by a capitalist ideology and market economy. The USSR was renamed the Russian Federation. Western culture freely crossed the opened borders of the “big” “open” society of the Russian Federation, and, in particular, Western tattoo magazines, professional tattoo machines and paints became available to everybody; tattooing professionalized and took on an artistic focus. Tattoo artists left the sphere of the “shadow economy”, the first legal tattoo parlors start opening. The social composition of the tattooed gradually changed: From the mid‑1990 those are not only the representatives of protest countercultures, but for the most part people who had successfully integrated into the new social reality: students of the universities, managers, employees of commertial firms and other social groups. Some tattoo styles are becoming the most popular: “old school”. “Polynesian”, “biomechanics”. Those who deliberately opposed their tattoos to the mainstream tattoo styles chose images that, in their opinion, directly reflected their protest mentality: skulls and bones, devils, and other devilish symbolism which the representatives of the late USSR countercultures exploited.

In the Research 1 (2010) and 2 (2019) in RF, we analytically distinguished two stages of getting used to tattoos: the stage of debut and the stage of involvement[16]. In debut the main object of protest is parents‘ prohibition of tattooing. At the stage of involvement, tattooing is associated with objection to (a) the standartisation of bodily beauty imposed by the fashion industry, the glamour standards of femininity/masculinity; (b) imposing standardization of life values; (c) religious norms promoting a particular bodily canon, and the Russian Ortodox Church ideology; (d) social and political systems, which strive to control and manage people’s lives. A person wants to be the Self, not the object of manipulation of the state and sociai institutions. The main value tattoo enthusiasts defended was the value of personal freedom and independence, which was expressed in the feminist formula “my body is my own business”. This situation was identified both in the Research 1 and the Research 2. However, when comparing the sudjective motives for tattooing in both researches we can conclude that in general the later generation of tattooed people had less pronounced protest and in most cases their protest mood was not associated with tattooing.

Before proceeding to the analysis of researches’ results, we need to make two preliminary remarks. First. Tattooing, like any social action, is driven by thinking[17] ‑ and we only consider those cases when tattooing is a conscious rather than an affective action. And if we analyze the protest motive in tattooing action, then we need first of all to show how exactly the protest thinking of tattoo enthusiasts works, what kind of narratives they produce in relation to those social institutions and social arrangements, the power of which causes their rejection. The analysis of the tattoo images themselves is secondary for us in relation to the analysis of the statements. Second. If the critical assessment of the narratives of the dominant culture by tattoo enthusiasts is voiced quite specifically, this does not mean that the tattoo images themselves necessarily consist of symbols that directly indicate the object of opposition. Plots of tattoos can be quite neutral (flowers, portraits of loved ones, children, pets, and much more), but the very fact that tattooing defies social norms is regarded by some of the tattooed as a protest practice. In ower following we will demonstrate the critical narratives of the respondents and, in some cases, illustrate them with examples of specific images. Third. The motivation for tattooing among tattoo enthusiasts of the past two decades is much more complex than that of tattoo enthusiasts of previous generations. We can not identify a single case when only one motive took place. In all cases, we are dealing with complex individual motivational cards, which are the aggregate of 16 motives that we have listed earlier. Some motives are more significant, others are less, and, what is important, the hierarchy of motives changes for a tattoo enthusiast through their lifespan. I.e. if the protest motive had dominated at the beginning of the tattoo enthusiast’s tattoo activity, then in the future it will not necessarily retain his leading position and may be pushed aside by motives that are more relevant at the moment. This third point is very important for understanding the semantic field in which the protest motive being a subject of our consideration exists.

An assessment of fashion and glamour standards

As we argued in the theoretical part of the article, fashion and the ideology of glamour can be those objects that may cause rejection of tattoo enthusiasts and which their protest can be directed to. In both researches, we asked respondents to describe their attitudes towards fashion and the ideology of glamour. In the Research 1, the overwhelming majority of respondents noted that they were not interested in fashion. To differentiate their serious pursuits from fashion, tattoo enthusiasts distance themselves from trendy social worlds as much as possible. Their assessment of the ideology of glamour as “prestigious consumption” of standards of beauty imposed by advertising and media (face oval, nose and lips shape, body proportions, etc.), and body look (wearing certain brands of clothing), ranged from moderately dismissive (“it exists, and good luck to it”) to disgusting (“It’s terrible, sickeningly!”). Glamour standarts were characterized as “cheap show‑offs”, and sometimes a radical position was expressed: “glamour must die”. Therefore, it seems logical that the majority of respondents agreed that tattoo culture shapes its own “bodily canon”, an alternative to the glamorous one which makes people “like a carbon copy”.

Research 2 (2019) explored a larger number of respondents expressed no interest in fashion, and the majority demonstrated the same attitude to glamourous standards as the respondents in the Research 1.

“Plump lips, voluminous breasts come in fashion, and women, trying to follow the standards of beauty, are trying to somehow adapt themselves to these standards. And this is no longer their personal and conscious choice. This is a pressure from fashion, men, because men are trying to dictate to women how they should look.” – Anastasia, 20 years old.

The minority of the respondents noted that both tattooing and glamour had already become a part of the popular culture, and therefore there was no contradiction between them. It was also argued that glamour exploits a tattoo as one of its tools by posting photos of tattooed celebrities on the pages of glossy magazines. And since the trend of gradual integration of tattoo culture into the fashion industry is evident, we can state the division of the tattooed into those who continue attributing their tattoos as an unconventional bodily practice, and those who regretfully, but understand the fragility of this alternative.

An assessment of the standardization of life values

As we stated earlier, glamourous standards extend not only to how a person should look like, but also to what values he should be committed to. Therefore, in both researches, we asked respondents to answer whether a standardization of life values took place in the RF society, and if so, what is their attitude to it. In the Research 1 (2010), all the respondents answered in the affirmative and expressed their hostility towards this. They noted that it was especially noticeable in television commercials. One of the illustrations was the respondent’s story about bringing contracted military service to the standard of success. A young man gives a girl large bouquet of roses, invites her to an expencive bar, they drink expencive cocktails, and when she askes: “Well, yes, but why are you like that?”, his answer is: “I can afford it!”. And then the slogan: “Contract service in the internal troops!”

“That is, it’s such an attitude that the contract service is for you to have money, to go to a disco and get drunk with vodka in the evening … That is, the main thing in the life is money, to buy a good apartment, a cottage and a fur coat for your wife, diamonds, to drive an expensive car in an expensive suit yourself, to drink not a cheap vodka, but an expensive cognac – that’s all, this is a success, this is happiness.” – Artem, 23 years old.

Fig. 4. Tattoos performed by Den Kouznetsov

“I believe that each person should choose his own way of life. Someone, perhaps, wants to be a hermit, go to some island and live there in conjunction with nature, he will not need any money and privileges of our modern society. Another person wants to live luxuriously. The third person wants to live a quiet and calm life in some modest district. For everyone, what is considered correct is right. I believe that one cannot set standards for anyone.” – Anastasia, 19 years old.

Opinions were expressed, that modern people are so different, have so different starting and financial capabilities and live in so different living conditions that to bring them to a single standard of life is utopia, doomed to failure. Tattooing of this type of tattoo consumers does not carry a protest charge, but acts only as a demonstration of an individual lifestyle. Here we can often find tattoos symbolizing adherence to the values of love and affection: family portraits, portraits of beloved dogs and cats, images of the tattoo wearers themselves surrounded by symbols close to their hearts (toys, landscapes, houses in which they grew up etc.). Some examples are demonstrated in Fig. 4.

An assessment of religion and the russian orthodox church

As we argued earlier, the Russian Orthodox Church is one of the main institutions that seeks to control the physical appearance of people and imposes an outright ban on tattoos. Therefore, we asked respondents about their own religiosity and about their attitude to religion and the Russian Orthodox Church. In the Research 1, when answering the question “Do you consider yourself a religious person?”, the majority of respondents said “no, I’m not a religious person”, one third – » yes, but I don’t fast and don’t participate in religious sacraments”, and the minimum number said “yes, I keep fasting and participate in religious ordinances”. At the same time, out of one third of respondents who considered themselves religious but didn‘t participate in religious sacraments, divorced the concepts of “faith” and “religion” and insisted on the concept of a “personal God” that was not specifically related to the church:

“I think that not only a believer can come to the church. For me the church is both a place of accumulation of positive energy and a place where certain channels open. And a person should gain positive energy, where he can ask for advice, and maybe he will get it, but it is so intimate where you have to say no to all your negative emotions: indignation, anger, hatred, outbursts of aggression, etc.” – Maria, 27 years old.

Fig.5. The left image is performed by tattooist Dmitry Martyushev, 2010th.

The author of the right image can’t be identified, photo is taken from http://joyreactor.cc/post/2171676

Most respondents to a greater or lesser extent demonstrated awareness of the main provisions of church dogma and agreed that there is a ban on tattooing in Orthodoxy. Respondents’ reaction to this fact ranged from doomed (“well, we have such a religion, what can we do?”) to openly hostile (“that’s why I hate it”).

Since, as mentioned earlier, tattoo enthusiasts tend to critically assess the ideological narratives of modern society, in relation to church dogmas, the act of tattooing is not just a challenge to the church’s norm of bodily purity, but a rejection of the Orthodox Church as a suppressive social institution. The overwhelming majority of respondents showed an unambiguous negative assessment of the Orthodox Church, describing it as an “institution of people management”, “super business”, “pumping money out of the population”, “pathos” and “falsehood”.

“Well, they’ll build a temple, well, there will be a priest – the priest is now a modern manager, he receives a percentage of the parish. Accordingly, he is trying to promote religion as actively as possible, plus the Russian Orthodox Church has a whole department that is engaged in the popularization of Orthodoxy. And accordingly, the larger the parish, the temple, the more they buy everything, the more the priest receives money. That is, he is an interested person in order to have a big parish, so that there is more money… I believe that now it is a business plus it is actively used by the authorities in order to be able to calm people in time, as in the Middle Ages.” – Artem, 23 years old.

All the respondents spoke about the fact that the current state uses the Russian Orthodox Church to control the population. Most noted that in the society the pressure from the church on public consciousness is strong. In contrast to the previously discussed negative attitude towards fashion, glamor and standardization of life values and their hardly traceable connection with the plots of tattoos, the negative perception of the church and its hierarchs is often directly reflected in tattoo images. (Fig. 5). In the left image, we see a plot that reflects the perception of the church as a business enterprise. The watch on the priest’s hand refers to a recent scandal when Patriarch Alexy came to the press conference wearing a watch decorated with diamonds and its coast was $ 50,000. In the right image we see a portrait of a clergyman wearing an Orthodox miter, with a skull instead of a face. Despite the skull historically has many meanings, in Christian iconography it symbolizes the Old Testament Adam and is often placed under the figure of Christ, and the hole composition symbolizes the victory over death. However, in this case, the intonation of the image is such that it allows us to interpret the plot as having the opposite meaning: the priest personifies death, or the religion is dead.

In the Research 2, an assessment of the activity of the Russian Orthodox Church was equally negative.

“Now more churches are being built than schools, so conclusions can be drawn… I used to live on Babushkinskaya[18], we had … a small park there, but they also decided to chop off some of the land for the chapel…. In general, I am in favor of removing all churches, all mosques, all objects of a cult from cities in general. Whatever their cultural value. I would remove all this and build parks there, public space… And in general, you can’t go in with your own candles. You should buy them in a church … The church is a commercial structure.” – Eugene, 35 y.o. Opinions were expressed that religion negatively influenced and influences science, progress, medicine. “That is, in our country people still go to the church for cancer treatment and pray. It is terrible.” – Nikita, 26 years old.

An assessment of the political and the social system

As skin represents the meeting place of the the individual and social environment, a protest aspect of tattoos explores complicated relationship between self and power of society. So the respondents were asked about political and civil freedoms in the RF. In the Research 1 (2010), the overwhelming majority of respondents noted that a personal choice of political course and free expression of one’s political sympathies do not exist in RF society, and civil freedom is only political slogans. A minority described the current political system as a dictatorship or noted that civil freedom is partial – i.e. exists only within the limits allowed by the authorities. Unlike prison tattoos, which plots directly express the protest mood of their owners, in a “big” society of the RF, the content of tattoo images mentioned above (close people, animals, flowers or just beautiful ornaments) does not always reflect the attitude of the tattoo enthusiast towards the suppressive essence of the RF state, but, as we stated earlier, the very fact of tattooing serves as a kind of negation and psychological compensation for political lack of freedom. But in some cases it does, and here we see two main interpretations of this theme. In the first case, the current political regime is interpreted as monarchical, and in Fig. 6 on the top left image, we see the face of Vladimir Putin wearing the Monomakh hat, worn by Russian princes and tsars since the Middle Ages. In the second case, the current political regime is treated as criminal and death‑causing. In Fig. 6 on the top right image, we see a portrait of Vladimir Putin with a skull instead of a face, and on his head ‑ a spider web, which refers to prison symbolics, and its threads represent the twigs of the prison bars. In Fig. 6 on the bottom image, we see the inscription» Putin is a thief”, which quite clearly says what the owner of the tattoo thinks about the current president.

Fig.6. Let image: Photo by Anatoliy Maltsev, 2010th.

Center image is performed by tattooist Oleg Shelepenko, 2010th.

Right image: Photo by Arina Morozova, 2010th.

“…in connection with the recent events with the rallies that were held this summer for fair elections of deputies, we can see that the state spits on the freedom of choice of our patrials, but there is no alternative. We can see an almost totalitarian system of governance and a reluctance to listen to the opinion of the citizens.” – Anastasia, 20 years old.

Some respondents argued that the country is moving towards 1937[19].

“Sooner or later, the hand of the state will touch everyone. Sooner or later, they will come to each family, to everyone. And if we follow the path that the bloody gebnya[20] is trying to advance, this will turn into the 1937.” – Pavel, 30 years old.

“I felt this very vividly during my studies at the institute, when we were being removed from classes so that we had to go and campaign for some ruling party, that we were obliged to stand with flags on the Red Square… I looked at the situation, at the psychological climate of the state organizations, at the people who worked there, at the atmosphere there…. That is, you can be yourself, but if you stand out, oppose the main shell of this system, then be prepared for the fact that this shell will wrinkle you actively.” – Anna, 22 years old.

“I could answer more specifically if I was interested in what is happening in politics. And so I feel it more on an intuitive level, on the level of prices increase, on the level of communication between people, on the ever growing conflict, restraint, on financial condition.” – Andrei, 38 years old.

Tattoos that ridicule the political regime of the last decade have the same message as the tattoos we talked about above, and use resembling stories.

The negative attitude to the current political situation turned out to be more radical on the one hand than in the Research 1 (2010), on the other hand, more doomed. Most of the respondents admitted that they did not feel pressure from the authorities on their consciousness, because they deliberately do not watch TV and by all means distance themselves from clashes with the authorities. At the same time, some respondents noted that although they did not feel the pressure of the authorities directly, they deeply experienced the injustice of the current political situation. In this case a tattoo acts just as an inner free self‑expesssion of its owner and as a way to psychologically distance oneself from civil bondage.

Fig. 7. Photos are taken from https://tattoo‑photo.ru

An assessment of the protest nature of contemporary tattooing

We now come to the final part of our analysis. We asked the respondents to answer whether, in their opinion, tattooing was a protest practice and to what extent, in general, modern Russian tattoo culture is connected with protest against all those institutions and social arrangements discussed above. In the Research 1 (2010), the minimum of respondents directly related the tattoo to the protest, indicating the protest motive as the main one. One respondent admitted that for him, a tattoo was primarily a political protest, which was also expressed in the content of his tattoos. In particular, Marilyn Monroe in the image of an American statue of liberty with a gun in her hand, and the inscriptions “DESTROY”, “REVOLUTION”, and “FUCK THE SYSTEM” were tattooed on his arm. In this case, “the system” correspondes not to a concrete political regime, communist, socialist or capitalist, but to political power as such. “Revolution” in this context is positioned as an anarchist action aimed at the destruction of the state as the main source of suppression of individual freedom. Marilyn Monroe in the image of an American statue of liberty symbolizes sexual and civil freedoms as the highest values which the bearer of this tattoo is committed to.

Some protest tattoos use the image of boxing gloves, which reflect the need for combat any manifestation of power and affirmation one’s own independence. (Fig 7, left image). Some tattoos use anarchist symbolics. (Fig. 7, central and right images). At the same time, anarchy is interpreted by its adherents in different ways. Some comprehend anarchy as the “mother of order” as it was seen by the first Russian ideologues of anarchism of the 19th‑20th centuries, Peter Kropotkin and Mikhail Bakunin. Some bearers of anarchist tattoos interpret “anarchy” as a synonym for chaos.

A small part of the respondents noted that the protest motive was not basic for them, but appeard to be very significant:

“If you live in society, then society imposes on you what your homeland is. If you live alone, regardless of society, if you are a hermit, abstract yourself from all this, then it’s completely different. I have, to some extent, a completely ascetic way of life, a cave and some kind of blanket would be enough for me. I give up comfort only in order to understand what comfort is. Now everything is available, but you are selling your time, your life, your freedom.” – Sergey, 36 years old.

Immersion in the space of tattoo culture, according to respondents, in this situation is considered as a way of avoiding the prevailing social reality, and this position is characteristic of those respondents who more than others emphasize the subcultural, non‑conformist status of tattoo culture.

The opinions of the rest of the respondents divided equally. Half of them claimed that for many people a tattoo was namely a protest, but for them it wasn’t.

“I just do not think the tattoo is any sign. I know many traditional, fairly conservative people who have tattoos. It seems to me that the tattoo in the modern sense has already turned into something like that … you can’t say that it is the hallmark of a protesting person in many cases, yes, but not necessarily.” – Victoria, 20 years old.

Respondents emphasized that for them the tattoo was more a decoration, self‑expression, an attempt to find themselves. In the latter two cases, tattoos often reflect the gender representation of their wearers. In male tattoos, two themes are exploited: the male as a warrior, a winner and the male as a father of the family, its protector. Women’s tattoos are dominated by representations of two legitimate types of femininity, enshrined in modern culture. The first type is, relatively speaking, a beautiful soft domestic cat, the second type is, relatively speaking, a beautiful independent bitch. The first type of femininity is symbolized by tender flowers, butterflies, kittens, angel wings, etc. The second type is symbolized by aggressive panthers, lionesses, tigresses, etc.)[21] Respondents argued that now it is difficult to call a tattoo a protest, since tattoos are becoming common.

These standards are formed not only under the influence of the peer reference groups, but also due to the presentation of tattooed celebrities in glossy magazines, which act as role models for their fans. For example, sometimes tattoo artists are faced with approximately the same customer request: “I want a tattoo like Angelina Jolie’s” or “I want a tattoo like Brad Pitt’s”. In these cases, tattooing doesn‘ work as challenge to the society, requiring special courage.

“A sign of courage in general is to do what you think is necessary, despite the fact that everything says that it is not necessary to do this way. Despite the consequences, not knowing what will happen next, take a step in which you may not be 100% sure, but something tells you that you need to do so, and you do it. Overcoming some difficult obstacles is courage.” – Maria, 27 years old.

Tattoo, in the opinion of thees respondents, does not correspond to this level. Here we meet again the value of personal freedom, whitch is of no nessesity to be reflected in a tattoo practice.

Half of the respondents indicated that the protest motive at an involvement stage, we indicated earlier, did not appear as dominant, but was present on their motivational map. They associated tattoo more with a rejection of the imposed living standards and the bodily image of a modern person than with the opposition to political regime that controls the social actions of individuals. The protest in this case was realized through the assertion of one’s bodily freedom, and the tattoo appeard to be “a piece of something of my own that no one can pick out anymore.”

“Of course, it is trivially, but this is a departure from the gray mass. At a certain age, my hair is colored red, and that’s all, a happy person, that is, I stood out from the crowd. And you can stand out only for yourself: some people make tattoos and do not even let them be shooted so that no one sees them. They do it, but they do not replicate in any way. This is the step that almost anyone can take, and if you ask yourself the right questions, then this is of course the degree of internal freedom.” – Dmitry, 28 years old.

In the Research 2 (2019), virtually none of the respondents associated a tattoo with a conscious protest. One third of the respondents noted that the protest motive has nothing to do with their tattooing. The remaining respondents confessed that even if a protest motive in their tattooing took place, it was unconscious. The objects of protest in many respects coincided with those indicated by the respondents of the Research 1: traditional culture values, conservatism of the society, imposed standards of appearance and life values, religious dogmas, snobbery of employers who do not hire tattooed employees. But sone respondents argued that tattooing would always be associated with a conscious protest, because the society will never fully accept it.

Majority of respondents argued that if you really want to protest, then you need to go to a political meeting. But, in their opinion, it does not make sense, since it is known in advance that all participants in the meeting will be taken to the police, and it will be difficult to get out of there.

One respondent convinced that a person should always protest against something:

This statement is accessibly in the context of the overseeing and governing nature of the state system, social institutions and culture industry. And this is that rare case when the symbology of tattoo images directly reflects the protest mood of its owner: aggressive scalps and devils on the arms, neck and head.

Summing up the assessment by tattoo enthusiasts of modern tattooing as a protest practice, we can conclude that, in general, the tattoo culture in the Russian Federation of the last decade as a whole is losing its protest orientation, and the protest message of individual tattoo enthusiasts is rather a rarity than a stable trend.

Conclusion

“Power” and “resistance” are really closely related notions that form a concept that has significant explanatory possibilities of why contemporary tattooing does not lose its protest potential. This is especially evident in a case of a prison tattooing, in a situation where the power and the object of power reside in a single closed physical space and hourly interact face to face. But if the concept of “power” has a predominantly sociological dimension, this, as Durkheim would say, is a “social fact” that has a coercive effect on individuals, then the concept of “resistance”, in addition to the sociological one, also has a psychological dimension. If power as a social fact exists constantly always and everywhere, then resistance is subject to significant fluctuations, since it is closely related to the mobility of the human psyche. A person can make an external or internal revolution and follow a protest path all his life. And a person may be disappointed, tired, submit or just distance himself from the social situation, realizing the senselessness of a protest behavior.

This is clearly seen in the attenuation of the protest motive in prison tattooing, and especially in tattooing in a “big” society.

On the other hand, modern tattooing does not carry the ideology of protest in itself. People involved in the practice of tattooing do give it certain senses. These meanings are formed under the influence of the economic, political, social, and cultural factors.

Therefore, the weakening of the protest motive in contemporary Russian tattooing can be explained by two main interconnected factors: (1) persons’ feeling of hopelessness to change something in the country and increasing political and social apathy and indifference; (2) tattoo culture of the last decade is losing its subcultural status, becoming a part of the fashion and beauty industries, integrating into the general cultural space of habitual bodily practices, perceived by the recipients of tattoo culture as something ordinary and therefore few reflexive.

But there are still tattoo enthusiasts out there who position their tattoos as resistance.

Références bibliographiques

Alferov Y.A., (1994), Penitentsiarnaya sotsiologiya: audiovizual‘naya diagnostika: (tatuirovki, zhargon, zhesty). (In Russian).

— Alferov Y.A., Penitentiary Sociology: Audiovisual Diagnosis: (Tattoos, jargon, gestures). Textbook. In 2 parts. Resp. in-t for advanced training of employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation. Domodedovo.

Atkinson M., (2003), Tattooed: the sociogenesis of a body art, London: University of Toronto Press Incorporated, 30-49.

Baldayev D.S., (2001), Tatuirovki zaklyuchennykh. (In Russian).

— Baldayev D.S., Tattoos of Prisoners: Album, St. Petersburg: Limbus Press.

Brain R., (1979), The Decorated Body, New York: Harper and Row.

Buster M., (2009), Hooligani 80. (In Russian).

— Buster M., Hooligans 80, Moscow: ANOK “T.C.I.” (In Russian).

Caplan J., (2001), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press.

Crossley N., (2001), The Social Body: Habit, Identity and Desire, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Crossley N., (2005), Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques: On Body Modification and Maintenance // Body & Society, 11/1.

Crossley N., (2006), Reflexive embodiment in contemporary society, Berkshire: Open University Press.

DeMello M., (2000), Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community, Durham: NC, Duke University Press.

Dubyagin Y.P., Dubyagina O.P., Smirnov G.F., (2003), Kul’t Tatu. Kriminal’naya i khudozhestvennaya tatuirovka. (In Russian).

— Dubyagin Y.P., Dubyagina O.P., Smirnov G.F., Tattoo Cult. Criminal and art tattoo, Moscow: Jurisprudence.

Douglas M., (1986), How Institutions Think. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Ebin V., (1979), The Body Decorated, London: Thames and Hudson.

Foucault M., (1978), The History of Sexuality Volume 1: An Introduction, New York: Pantheon.

Foucault M., (1988), Technologies of the Self in: “Technologies of the Self. A seminar with Michel Foucault” edited by Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patric H. Hutton. London: Tavistock Publications Ltd, 18.

Gernet M.N., (1924), Tatuirovka zaklyuchonnykh gor. Moskvy. (In Russian).

— Gernet M.N. Tattoo of prisoners in Moscow // The criminal world of Moscow: a collection of articles: A.M. Aronovich, N.N. Gedeonov, M.N. Gernet [et al.]: With photographs, figures and diagrams / edited and with a foreword by prof. M.N. Gernet. Moscow: Law and life.

Gilbert S., (2000), Tattoo History: A Sourcebook, San Francisco: Juno Publishing.

Goffman E., (1961), Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. New York: Anchor Books Doubleday & Company, Inc. Garden City.

Horkheimer M., Adorno T., (2001), Dialectic of Enlightenment, Stanford: Stanford University Press, California, 100.

Ivanov D., (2015), Glam capitalism. Mir brendov, trendov I tresha. (In Russian).

— Ivanov D. Glam Capitalism. The world of brands, trends and trash, SPb., Strata.

Kozinets R.V., (2002), “Can Consumers Escape the Market? Emancipatory Illuminations from Burning Man //“, Journal of Consumer Research, 29/1, 20-38.

Kosut M., (2015), Tattoos and Body Modification. In: James D. Wright (editor-in-chief ), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, 24, Oxford: Elsevier, 32-38.

Murray J.B., Ozanne J.L., (1991), The critical imagination: Emancipatory interests in consumer research // Journal of Consumer Research, 18/2, 129-144.

Oleinik A.N., (2001), Tyuremnaya subkul’tura v Rossii: ot povsednevnoy zhizni do gosudarstvennoy vlasti. (In Russian).

— Oleinik A.N. Prison subculture in Russia: from everyday life to state power, Moscow: INFRA-M.

Popper K.R., (1966), The open society and its enemies, London and Henley, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Rubin A., (1988), Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body, Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History.

Styopin V.S., (2010), Kul’tura. (In Russian).

— Styopin V.S. Culture // New Encyclopedia of Philosophy. M.: Mysl, Vol. 2, 344.

Tattoos from Russian Prison. URL: https://www.instagram.com/got_chif/?utm_source=ig_embed (date of the application 20.11.2019).

Vorobieva E.S., (2018), Tatuirovaniye kak ob’yekt sotsiologicheskogo issledovaniya. Teoretiko metodologicheskiye aspekty. (In Russian).

— Vorobieva E.S., (2018), Tattooing as an object of the sociological research. Theoretical and methodological aspects. The dissertation for the degree of Candidate in Sociology. Moscow: Institute of Sociology of the Federal Center of Theoretical and Applied Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 157-214). URL: https://www.isras.ru/files/File/Dissert/Vorobeva_dissert.pdf (date of the application 20.11.2019).

Vorobieva E.S., (2018), O ch’om rasskazyvayet tatuirovannoye telo: genderniye aspekti v opyte vizual’noy sotsiologii. (In Russian).

— Vorobieva E.S. What a tattooed body talks about: gender aspect in the experience of visual sociology. INTER, Vol. 10, N0 16, 70-80). URL: https://www.inter-fnisc.ru/index.php/inter/article/view/5843/5668 (date of the application 20.09.2020).

Yunge M., Binner R., Bordyugov G., (2008), Vertikal’ bol’shogo terrora. (In Russian).

— Yunge M., Binner R., Bordyugov G. Vertical of the Great Terror. Moscow: New Chronograph.

[1].↑ In the article, when we speak of “Russia” we use this word as an “umbrella” term, relying upon the tradition of Russian scientific historical literature, in which it is customary to use the following names of the Russian state since the 18th century to the present: “Russian Empire” (November 1721 ‑ September 1917), “Russian Republic” (September 1917 ‑ January 1918), “Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic”, RSFSR (January 1918 ‑ December 1922), “the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics”, USSR (December 1922 ‑ December 1991), and “the Russian Federation”, RF (since December 25, 1991). In each specific case, we tried to clarify what time period is involved.

[2].↑ When using the term “a big society”, we follow Erving Goffman’s concept of a social space of modern societies. Hoffman divides the entire social space into a “basic social arrangement” and “total institutions”. In particular, he writes: “A basic social arrangement in modem society is that the individual tends to sleep, play, and work in different places, with different co‑participants, under different authorities, and without an over‑all rational plan. The central feature of total institutions can be described as a breakdown of the barriers ordinarily separating these three spheres of life.” Prisons serve as a clear example of a total institution “where a large number of like‑situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life.” Goffman E. Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. New York: Anchor Books Doubleday & Company, Inc. Garden City, 1961, 12-14. The term “a big society” can be applied to both socialist (in the USSR) and capitalist (in the Russian Federation) political regimes.

[3].↑ Recent Russian sociological polls show that public consciousness preserves the perception of tattooing as deviant behavior, and the assessment of tattoos as ugliness of the body dominates. To this day, a tattooed woman can still hear a “prostitute” in her address, and employers may unlawfully refuse a tattooed job applicant.

[3].↑ Recent Russian sociological polls show that public consciousness preserves the perception of tattooing as deviant behavior, and the assessment of tattoos as ugliness of the body dominates. To this day, a tattooed woman can still hear a “prostitute” in her address, and employers may unlawfully refuse a tattooed job applicant.

[4].↑ Here we use the terminology of Karl Popper and follow his concept of two tipes of society. Popper K.R. The open society and its enemies. London and Henley, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966.

[5].↑ For example, among the ancient Incas, a simple change in hairstyle was punishable by death.

[6].↑ Using the term “culture universals”, we follow a prominent Russian philosopher of science Vyacheslav Styopin, who defines them as forms of rational thinking inherent in certain societies and as schematisms that determine human perception of the world, his understanding and experience. Styopin distinguishes two large and interconnected blocks of culture universals. The first block refers to the categories that fix the most general, attributive characteristics of objects included in human activity. Their attributive characteristics are recorded in the categories: “space”, “time”, “movement”, “thing”, “attitude”, “quantity”, “quality”, “measure”, “content”, “causality”, “chance”, “necessity”, etc. The second block of culture universals, which our article shapes, refers to “special types of categories through which the definitions of a person as a subject of activity, the structure of his communication, his relationship to other people and society as a whole, to the goals and values of social life are expressed: “man”, “society”, “consciousness”, “good”, “evil”, “beauty”, “faith”, “hope”, “duty”, “conscience”, “justice”, “freedom”, etc. These categories in the most general form fix the historically accumulated experience of the individual’s inclusion into the system of social relations and communications”. Styopin V.S. Kul‘tura//Novaya filosofskaya entsiklopediya. M.: Mysl‘, 2010, T. 2, 344. (Styopin V.S. Culture // New encyclopedia of Philosophy. M.: Mysl, 2010, Vol. 2, 344). (In Russian). The term “culture universals” is close to Durkheim’s “collective ideas”, but we consider it to be more accurate in the context of our discourse.

[7].↑ 1Cor. 6:19.

[8].↑ In the sosiety of the USSR, Russian Orthodox chirch didn’t play any sugnificant role, the outward appearance of the “Soviet patrial” was carried out by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union via political governing apparatus at the enterprises and widespread distribution of special brochures such as “The external appearance of a Soviet woman” or “The external appearance of a Soviet man”. In schools, this issue was discussed at the lessons of “the political information”.

[9].↑ Gernet M.N. Tatuirovka zaklyuchonnykh gor. Moskvy. (Tattoo of prisoners in Moscow // The Underworld of Moscow: a collection of articles: A.M. Aronovich, N.N. Gedeonov, M.N. Gernet [et al.]: With photographs, figures and diagrams / edited and with a foreword by prof. M.N. Gernet. Moscow, Law and life, 1924). (In Russian).

[10].↑ “Great Terror” is a term of modern historiography that characterizes the period of the most massive political repressions in the USSR in 1937‑1938. The tightening of repressions affected not only criminals, but also members of other social groups, from peasants to officials, who were suspected of anti‑Soviet activities. “Great Terror” was also tied with the strengthening of the “vertical of authorities”.

[11].↑ German historians Mark Junge and Rolf Binner associate the beginning of the “Great Terror” primarily with the preparation of the Soviet Union for a war with Nazi Germany. See: Yunge M., Binner R., Bordyugov G. Vertikal’ bol’shogo terrora. Moscva, Novyy khronograf, 2008. (Yunge M., Binner R., Bordyugov G. Vertical of the Great Terror. Moscow, New Chronograph, 2008). (In Russian).

[12].↑ Alferov Y.A. Penitentsiarnaya sotsiologiya: audiovizual‘naya diagnostika: (tatuirovki, zhargon, zhesty). (Alferov Y.A. Penitentiary Sociology: Audiovisual Diagnosis: (Tattoos, jargon, gestures). Textbook. In 2 parts. Resp. in‑t for advanced training of employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation. Domodedovo, 1994). (In Russian). Dubyagin Y.P. Dubyagina O.P., Smirnov G.F. Kul’t Tatu. Kriminal’naya i khudozhestvennaya tatuirovka. (Dubyagin Y.P., Dubyagina O.P., Smirnov G.F. Cult Tattoo. Crime and art tattoo. Moscow: Jurisprudence). (In Russian).

[13].↑ Oleinik A.N. Tyuremnaya subkul‘tura v Rossii: ot povsednevnoy zhizni do gosudarstvennoy vlasti. (Oleinik A.N. Prison subculture in Russia: from everyday life to state power. Moscow: INFRA‑M, 2001). (In Russian).

[14].↑ In the prisons of the “red belt” prisoners interact with the prison administration. In the prisons of the “black belt” they do not.

[15].↑ Buster M. Hooligani‑80. (Hooligans‑80, Moscow, ANOK “T.C.I.”, 2009). (In Russian). Buster has never been a professional researcher, but since he was directly within the countercultural movement, his interviews provide more for understanding Soviet tattoo culture than professional anthropological and sociological researches.

[16].↑ Debut is a stage of forming the initial motivation that tattoo enthusiasts get and which prompts them to their first “tattoo experiment”, and the involvement is a stage of forming a more reflective attitude to their tattoo practices and the expansion of the motivational sphere that detakes place in the process of accumulating the practical experience of tattooing. The formation of motivation for tattooing is analyzed in detail in the Candidate of Sociology dissertation by E.S. Vorobieva. (Tattooing as an object of the sociological research. Theoretical and methodological aspects. Moscow, Institute of Sociology of the Federal Center of Theoretical and Applied Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2018, 157‑214). (In Russian). URL: https://www.isras.ru/files/File/Dissert/Vorobeva_dissert.pdf (date of the application 20.11.2019).

[17].↑ We analyze tattooing as goal‑rational or value‑based rational action in Max Weber’s terminology. Affective tattooing also takes place, but in this case, we have no serious grounds to evaluate such tattooing as protest, since the later respondents’ rationalization of their tattoo practices significantly reduces the validity of the conclusions.

[18].↑ Babushkinskaya is a district in Moscow.

[19].↑ 1937 is the year of the peak of Stalinist repressions, mass landings in prisons and shootings down without trial.

[20].↑ Gebnya is the slang name of the Committee of the State Security (CGB) in the USSR.

[21].↑ For more details see: Vorobieva E.S. O ch’om rasskazyvayet tatuirovannoye telo: genderniye aspekti v opyte vizual’noy sotsiologii. (Vorobieva E.S. What the tattooed body talks about: gender aspect in the experience of visual sociology. INTER, 2018, 10/16, 70‑80). (In Russian) URL https://www.inter-fnisc.ru/index.php/inter/article/view/5843/5668 (Date of the application 20/09/2020).