Référence électronique

Rolle V., (2025), « Tattoo in Museums. Conditions and Limitations of Access to Cultural Institutions », La Peaulogie 12, mis en ligne le 14 février 2025, [En ligne] URL : https://lapeaulogie.fr/tattoo-museums

Maître de conférences, Nantes Université, Centre nantais de sociologie (CENS – UMR 6025).

Référence électronique

Rolle V., (2025), « Tattoo in Museums. Conditions and Limitations of Access to Cultural Institutions », La Peaulogie 12, mis en ligne le 14 février 2025, [En ligne] URL : https://lapeaulogie.fr/tattoo-museums

Abstract

The scientific literature on tattoo has adopted the terminology used in the world of tattooing to qualify the practice, and although analyses of the professional side of tattooing have improved since regulations came into effect, research on its social acknowledgement as an art form outside the tattoo world is rare. Broad cultural shifts have played a part in bringing tattoo into the museum space, which has given certain tattooists a new platform to exhibit their work. To gain a deeper understanding of this recent access, the present paper will address the changes in cultural consumption and cultural policies that, since the 1980s, have partially blurred the cultural boundaries. It will then examine the dual movement that has developed as a result of these blurred lines: artistic appropriation of formerly marginalized or devalued working-class practices such as tattooing, and the call for artistic recognition from “art outsiders”. From this perspective, it will show how cultural hierarchies are producing social domination despite being reshaped.

Keywords

Tattoo, Popular culture, Access to museums, Cultural shifts, Cultural hierarchies

Résumé

La littérature scientifique a adopté la terminologie utilisée dans le monde du tatouage pour qualifier la pratique. Bien que les analyses sur le pan professionnel du tatouage se soient développées depuis l’entrée en vigueur d’une réglementation des studios, les recherches sur la reconnaissance sociale du tatouage en tant que forme d’art restent rares. En l’occurrence, des changements culturels plus larges semblent avoir joué un rôle dans l’introduction du tatouage au musée, offrant à des tatoueurs un nouvel espace d’exposition. Pour mieux comprendre cet accès récent, le présent article explore d’abord les changements relatifs à la consommation et aux politiques culturelles qui ont, depuis les années 1980, partiellement estompé les frontières culturelles. Il examine ensuite le double mouvement qui s’est développé dans le sillage de ce brouillage : l’appropriation artistique de pratiques populaires autrefois marginalisées ou dévalorisées comme le tatouage et la quête de reconnaissance artistique d’« outsiders de l’art ». Dans cette perspective, la conclusion interroge la manière dont les hiérarchies culturelles continuent à produire de la domination malgré leur recomposition.

Mots-clés

Tatouage, Cultures populaires, Accès aux musées, Transformations culturelles, Hiérarchies culturelles

Since Clinton Sanders’ pioneering study on contemporary tattooing in 1989, the literature has adopted the terminology used in the “tattoo world” to qualify the practice as an “art form” and its practitioners as “tattoo artists”. With the growing enthusiasm for tattooing since the mid‑1990s, research has focused on the socio‑historical processes popularising the practice (Caplan, 2000 ; DeMello, 2000), and generated and extended knowledge on the unprecedented feminization and the gendered consumption of this body modification (Atkinson 2002 ; Gill, Henwood & McLean, 2005). The mass media have helped to build an image of “middle‑class individuals with fine art tattoos” (DeMello, 1995), but despite this representation, it remains a predominantly popular practice that has never been entirely disassociated from its working‑class and deviant roots. This points to a dichotomy between mainstream users who need to morally justify getting a tattoo (Irwin, 2001) and the “artistic value” of the inked images invoking a “positive form of deviance” (Irwin, 2003) among “tattoo collectors” (Vail, 1999). In any case, praise for the “artistry” of professional tattooists seems to contribute to the legitimization of the now customized body modification.

According to Mary Kosut (2013), in recent decades the profession has become segmented through an “inner artification” process that increasingly distinguishes academy‑trained middle‑class “tattoo artists” and working‑class self‑taught “old‑timers”; the former are more likely to seek artistic recognition, especially since tattooing has become an alternative career to the crowded fine arts market they initially aspired to join. They also relate to tattoo aesthetics in different ways. Although the stratification of tattooing is clearly shaped by generational and educational gaps, it is also based on a commitment to an alternative lifestyle (Rolle, 2016). Such involvement acts as dominant and informal selective criteria for entering a market that is still informally organized and also partially regulated (the government policies in place only cover sanitary matters)[1]. Since the mid‑2000s, more and more academically trained professionals (in applied or visual arts) have been joining the profession, but they have not significantly challenged the current structure and its functioning. And despite promoting iconographic innovations that appeal to new customers who were previously uninterested in tattooing, they have not yet overturned the prevailing aesthetic in the tattoo world. The differentiation between a “tattoo artist”, a “good tattooist” and a “bad tattooist” mainly acts as a distinction between professionals in a highly competitive market in which skill enhancement supersedes art production to satisfy client wishes, the majority of which are for figurative and popular worldwide designs (Rolle, 2013).

In Western countries, analysis of professional tattooing has improved since regulation processes were put in place, yet art historians[2] are just beginning to address the subject of the social acknowledgement of tattoo as an art form outside the world of tattoo. Through adopting and championing the indigenous terminology in this sphere, academics have become instrumental in extending the discourse and deepening the understanding of the field. Tattooing is becoming a legitimate research field in a context of considerable growth, media exposure and institutional exhibition, all of which promote tattoo as an “art form”. Nevertheless, it remains associated with a lowbrow body modification by the intellectual fractions of higher and liberal professions who regard the practice with disdain (Rolle, 2016). This begs the question of whether “artification” (Heinich & Shapiro, 2012) of the tattoo is indigenous or whether it has taken place externally. In France, broad cultural shifts have contributed to bringing the tattoo into the museum space, a move which has allowed the work of certain tattooists” to be exhibited. In order to understand this access, the first section of this paper will address changes in cultural consumption and cultural policies that, since the 1980s, have partially blurred the highbrow‑lowbrow boundaries established in the 19th century (Levine, 1988). Formerly marginalized or devalued working‑class practices have thus been popularized and moved up the social hierarchy to be exhibited in established cultural institutions. The second section will discuss this access with reference to tattoo. Indeed, the fuzzy definition of culture has created a dual movement: appropriation by contemporary artists, and claims for artistic recognition by tattooists and new supportive intermediaries, the logic and impacts of which must be analysed. To this end, the conclusion will show that cultural hierarchies, albeit reshaped, are still producing social domination.

From the end of the 19th century, sociological studies – such as Thorstein Veblen’s model of “conspicuous consumption” and Georg Simmel’s fashion theory – assume that consumption trends follow a top‑down movement. What people buy and use sends a social membership signal and serves a dual distinction process: it helps to set the upper classes apart from the lower social classes, and distinguishes individuals from their peers. This understanding also underlies Pierre Bourdieu’s 1970s theory of social stratification based on cultural taste, that states while social distinction is played out between the upper and lower classes, it mainly happens on a smaller scale within each social class that is itself further subdivided into various “class fractions”, some of which dominate others. Individuals from the lower‑class fractions tend to show “cultural goodwill” by modelling their practices and lifestyle on the prevailing taste patterns of the higher class fractions. In a nutshell, the ruling class fractions compete to impose their cultural perceptions and appreciations, thus enabling them to distinguish themselves from others, derive benefit from this distinction, and in turn create desirable social norms. Working‑class lifestyles are need‑driven (lack of cultural and economic capital), thus creating a “taste of necessity”, which in turn translates into “autonomous” tastes and lifestyles that are separate and therefore primarily outside of these “games of distinction” (Bourdieu, 1996 [1979]). This theoretical framework has since been criticized, in particular for its “miserabilist” or “populist” view about the working classes that for Gérard Mauger (2013), sometimes reflects the ambiguous relationship academics have with that social entity[3]. Nonetheless, it is a model that is still relevant today and has been widely remodelled.

Social structure transformations in Western societies, in addition to shifts in modes of exposure to culture, have fostered less compartmentalized consumptions between “refined” and “plebeian” products. Along with the rise of mass education, the expansion of the tertiary sector led to greater upward social mobility in France during the “Glorious Thirties” following the Second World War (Fridman & Ollivier, 2004). The development of mass communication, from television to cyberspace, has no longer allowed the upper classes to live in almost cultural self‑reliance (Pasquier, 2005a). These changes have increased the simultaneous consumption of highbrow and lowbrow goods. However, they have not led to the cultural relativism predicted by postmodernism. Cultural hierarchies have not vanished. Social distinctions are reshaped by diversified and unequally valued patterns of consumption and the ways in which the same activity or product is being consumed. The idea that “omnivore” tastes would be a high‑status prerogative is contradicted by recent studies in France as well as in the UK (Coulangeon & Duval, 2013). Although fee‑paying high cultural practices remain scarce among working‑class people with low levels of education and income, cultural consumption extends to a broad range of interests in this social category. But this eclecticism usually differs in its content from upper and middle‑classes, except in the case of the ascending trajectory in which the same cultural activity may be practiced in a “universe of meaning” that remains close to the individual’s original social class (Siblot et al., 2015). Thus, practices that transcend classes do not necessarily reflect a common way of life for all members unless working‑class people fully acculturate to their new social class.

The same practices are used by different social groups and this hampers the quantitative analysis of cultural consumption, nevertheless, distinction games and taste hierarchies have not disappeared when observed on a qualitative level. Subtler than before, cultural inequalities operate on multiple levels aside from wealth: social origin, education, occupation, gender, ethnicity, age and sociability. Therefore, it cannot be said that “high culture” (opera, theatre, literature) does not still epitomize respectability, however, it has lost its ability to embody a single and dominant model of consumption. As a consequence, popular culture has become more widely celebrated and is consumed shame‑free. However, this shift reflects not only how the changes in symbolic goods are received but also how they are politically framed.

In France, cultural policies have significantly supported culture (in particular museums and heritage institutions, fine and performing arts) since the creation of the Ministry of Culture in 1959. In 1981, there was a second phase of institutionalization when the socialists came to power, which was characterized by an interconnected process of professionalization and the broadening of cultural action (Dubois, 2009 [1999]). The will to reconcile economy and culture, echoing a wider movement promoting culture as an economic sector, has led to a “managerial turn” (private model applied to public sector)[4]. New employment policies have resulted in substantial budget growth and the professionalization of cultural management. The increase in specialized training has nevertheless failed to unify the profession whose outlines reproduce the fuzzy definition of culture. The empirically proven unsuccessful effects of “cultural democratization” on consumption, linked to elite culture proselytization during the first institutionalization phase of cultural action, has been joined by a relativist principle of “cultural democracy” that exists alongside it. Cultural policy has thus extended the market to alternative, popular, regional, and traditional cultural productions that were previously marginalized or excluded from the framework and from now on are regularly incorporated in social inclusion policies.

These transformations have led to the spread of an “entrepreneurial culture” (Poulard, 2007), particularly within big museums and institutions who appoint managers or senior officials instead of scientific curators. This new management mindset is on the rise and uses marketing tools to target new audiences through cultural mediation and rehabilitated cultural forms, the results of which have so far been less successful than hoped according to Vincent Dubois (2009 [1999]). Using quantitative attendance assessments to legitimize the allocation of financial resources, it helps to promote project‑based work in museums, is often adopted for missions that exceed the museum’s original cultural scope, and is a managerial shift that has given rise to more temporary exhibitions. In this context, museums call on independent curators to work with museum staff (Poulard, 2007). Nowadays, half of curating positions are filled by freelancers, of which three‑quarters combine curating with another core function such as artist, art director, art teacher, art school director, gallery owner or employee, art critic, etc. Most have upper‑middle class backgrounds and are highly educated and cultivated (Jeanpierre & Sofio, 2009). It can be assumed that there are more freelancers curating in sectors that are less legitimized than fine arts, and that their social and professional profiles vary, for example, journalists and collectors with specialist knowledge in a narrow field of expertise that is not covered by the museum’s standard cultural scope.

The fact that culture is a broad and elusive category of public action enables the diversification of products, subsidized practices, professionals, and targeted (but not necessarily reached) publics. As a result, there no longer seems to be a hierarchy between “insider” and “outsider” art and “highbrow” and “lowbrow” culture. The so‑called “relativism”, “neutral expertise” and “social diversity” advocated for have not depoliticized cultural action, observes Vincent Dubois, but rather obscured power games behind more complex interrelationships between a larger set of cultural actors. It is therefore necessary to clarify the differentiated effects of cultural circulation patterns, given that they usually take two main forms: first, when established artists borrow images from popular culture to produce art, and second, the well‑studied pattern of cultural circulation linked to rehabilitation processes. The former, Pop Art, was the first collectively organized and institutionally recognized movement explicitly playing with commercial and lowbrow products. As shown by Joni Cherbo (1997), it reactivated the recurring question of “what is art?” or, more precisely, reshuffled who was entitled to label and value art. The market and a new wealthy upper‑middle class fraction associated with gallery owners had challenged the previously unilateral power of museums and art critics. For the latter, artistic recognition of a cultural practice requires an active process of promotion. Howard Becker (1988 [1982]) notes that “artist‑craftsmen” become distinguished from “ordinary craftsmen” by attempting to place all or part of their work (produced according to beauty and artistic standards rather than utility and virtuoso skill) in “minor art worlds” they contribute to setting up or in established art worlds through the support of gatekeepers.

Recently, more attention has been given to the role of the wide range of symbolic transformations and cultural actors involved in the transition of non‑art to art. A process of “artification” (Heinich & Shapiro, 2012) is fostered by changes in content and production criteria (aesthetic purposes), new identification modes (artistic labelling), access to institutionalized spaces (exhibitions in museums, galleries), public dissemination exposure (publishing books, trade magazines, media) and comments (critique, scientific study). These pragmatic approaches underline that the same activity can be performed at the artistic and ordinary level, thereby creating spaces of production and visibility in which practice and meaning coexist alongside one another. However, this literature does not take into account how these processes simultaneously reproduce and rework social and cultural hierarchies[5]. With this in mind, the next point examines that dual movement of circulation – artistic appropriation and claims for artistic recognition – in the case of tattooing, and more generally, the logic underlying these movements, and the shifts they reflect in the organization of the artistic field and the tattoo world.

Tattooing only started being used by contemporary artists from the late 1960s onwards, when the range of artistic medium expanded and there was a coincident reaction challenging the early 20th century minimalist aesthetic – which had become the dominant norm – in contrast to the logic of ornament (Golsenne, 2013). These uses are rarely studied, remaining one‑offs and episodic, however, they have one thing in common: they play with the dishonourable and elective power of body marking which in turn acts as a boundary between the self (the individual), the alike (the community) and the others (the society)[6]. From the 1990s onwards, some artists have, implicitly or explicitly, brought into play the working‑class grassroots of tattooing to call cultural hierarchies into question. Jean‑Luc Verna – a French artist who is part of the punk movement and has an art school background – poses naked for a series of photos inspired by fine art painting and sculpture, and rock or punk live performance. One such example is Crucifixion (2011), which is the artist’s interpretation of Goya’s Christ Crucified (1780) and the Queen singer Freddie Mercury being cheered by the audience at Wembley stadium in 1986. The erudite and popular collide, with a collective memory and his personal trajectory often being displayed in such a way that it also troubles gender. His work as a painter and performer is more broadly aimed at challenging the cultural, heterosexual and social norms linked to the religious legacy he inherited from his upper‑class family and broke away from. His tattoos embody this state of mind and, without being claimed as an artistic medium, contribute to his performances and the construction of his artistic persona.

For Belgian plastic and visual artist Wim Delvoye, tattooing does not relate to a personal lifestyle but to a medium that transgresses artistic boundaries. Famous for Cloaca, an excrement‑producing machine replicating the human digestive tract (a work he later duplicated in several versions), he is on an endless quest to push the limits of art, which he pursues through the transgression of cultural hierarchies: the bourgeois set against the working class, luxury against mass production, sober against decorative, and cleanliness against dirtiness. Waste and ornament are thus treated on the same footing because they breach the minimalist aesthetic associating beauty with purity, without breaking from the non‑utilitarian definition of art that has defined it since the 19th century. In this manner, Delvoye opened Art Farm (2003‑2010) in China. It was a place where live piglets would be inked with traditional tattoo designs – usually referring to popular or alternative cultures (such as skulls, Madonnas, and Japanese patterns), cultural industry icons (like Walt Disney characters) or commercial and luxury brands (such as Harley Davidson and Louis Vuitton) –, grow up under the scrutiny of cameras and die of old age before being tanned or stuffed and sent back to their buyers. In 2008, the artist went one step further and sold a human back. Tim Steiner’s back (see Delvoye’s Tattoo Works on his website) was almost entirely tattooed by tattoo artist Matt Lindsey (subcontracted for the project) and then sold to a German art collector for €150,000. The sale agreement stipulates that the then 32‑year‑old Swiss musician must display his tattoo three times a year in galleries or museums, and also provides for the removal of the skin after death to allow the circulation of the piece on the art market (Rolle, 2020)[7].

However, non‑utilitarianism does not go with an ethic of selflessness. Wim Delvoye states that the artistic value of an object depends on its sale on the art market and public recognition. Apart from the actual making of the piece of art, that he usually delegates to highly skilled craftspersons, he always seeks out innovative ways of negotiating the financial value of his artwork on the market. In the past, this has consisted of printing convertible bonds to propel Cloaca on the stock market, creating a company limited by shares for Art Farm, or having recourse to the law authorizing prostitution (e.g. a corporeal service delivery) in Switzerland to allow the sale and display of Tim. Delvoye challenges as much as he overtly (some would say cynically) uses an art field logic. He rejects the romantic notion of the lone and accursed artist and has built a thriving company creating branded art products – in this respect, see the imitation of the Walt Disney corporate signature. Indeed, it is no longer the virtuoso skills demonstrated in the artwork that make the artist but his power, as a labelled artist, to promote the goods he conceptualises as artworks (Moulin, 1997) – in this particular case, the mixing of high technology or decorative and physical popular arts with trivial daily and bodily matters. This transubstantiation, a belief that the artist compares to religious faith, is triggered by the simultaneous complicity and competition connecting cultural and economic actors on the art market, as well as the judiciary power embodied by the attorneys:

“In fact, I thought that the real artisan in Tim’s case wasn’t the tattooist, me and someone else, but rather the lawyers. Thanks to them I could sell that work. And it’s by means of this sale that Tim has become a piece of art for the media and thus the public.” (Bruno, 2014, 128)[8]

Similar to Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst or Ai Wei Wei, Wim Delvoye’s case testifies to the progressive shift from the “vocational regime”, which prevailed over the “academic regime” in the 19th century, towards an “entrepreneurial regime” in current contemporary art (Borja & Sofio, 2009). Embracing the neoliberal principles of a new capitalist state, he still conforms to the “ideology of a continuous overtaking” (Moulin, 1997) leading to the perpetual question of what is art and who is entitled to label art. In this regard, the use of lowbrow appears to be legitimate as it is associated, by the artist and by art critic Pierre Streckx (2007), with a “basic aesthetic”, referring not to a “primitive” otherness but to popular culture. Lowbrow products would have a stronger emotional appeal, be instantly understandable and more “democratic” than highbrow products which could potentially be seen as harder to access aesthetically[9]. Identified with “folk art”, tattoo is seen as simplistic, and even if it is praised in a context that lauds “cultural democracy”, this characterization has far from broken with hierarchies of cultural legitimacy. Furthermore, tattoo remains assigned to museums of “cultures and civilizations” created in the aftermath of the crisis that hit “ethnological museums” during the 1990s. In that context, parts of the Musée de l’Homme collections were transferred to new institutions (the Quai Branly Museum in Paris and the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations in Marseille) in a bid to promote “dialogue between cultures and civilizations”, through an aesthetic rather than a strictly scientific lens. Political authorities struggling with France’s colonial past pushed for this move (Mazé, Poulard & Ventura, 2013).

In this respect, the temporary Tatoueurs, tatoués exhibition hosted at the Quai Branly Museum inaugurated in 2006 by former French president and strong supporter of “primary arts” Jacques Chirac seems exemplary. Lasting for an exceptional 530 days (from 6 May 2014 to 18 October 2015), the exhibition was directed by freelance curators Anne Richard and Julien Deflisques (known as Anne & Julien). Its purpose was very similar to that of their previous exhibitions “Hey! Modern art & pop culture”, held in 2011 and 2013 at the Halle Saint Pierre (a former covered market and now a museum of “raw”, “outsider” and “naive arts”). The aim was to give artistic merit to alternative scenes by bringing together lowbrow arts (underground comics, pop surrealism), outsider arts, and also street art and tattoo[10]. Up until then, tattoo had been labelled as an “immemorial” custom of body modification, and tattooing was restricted to an anthropological lens. In France, the private museum Dapper, specialized in African, Caribbean and diaspora cultures and arts, was the first to juxtapose tattoo as a collective rite of passage in traditional societies and a new form of self‑expression in postmodern societies (Signes du corps, 23 September 2004 to 3 April 2005).

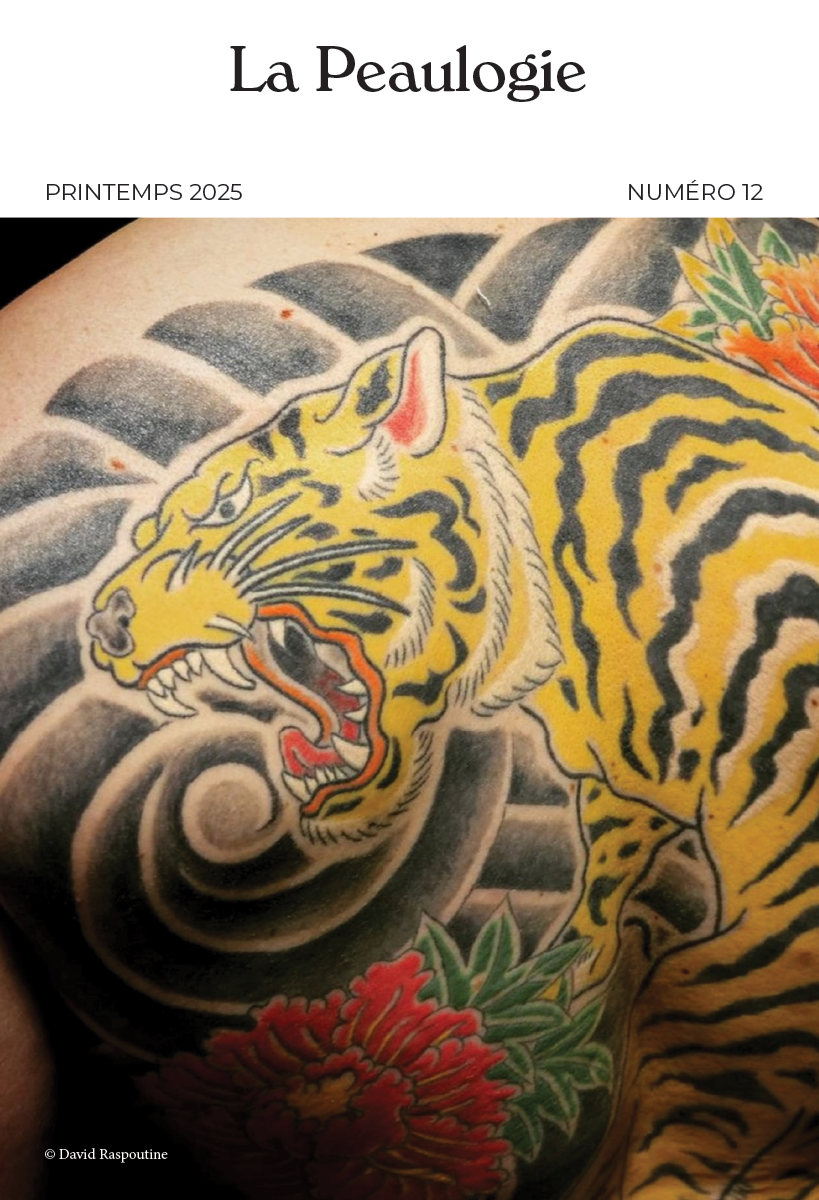

In any event, that tattooing only gets a rightful place in institutions dealing with various forms of less legitimate “primitive” cultural matters implies a sense of simplicity (early stages of human creation) and instinctiveness (creation out of cultivated knowledge). Trying to defy these preconceptions leads to a distancing from an ethnological approach. Even if the latter still underlies the display of tattoo in museums, the rhetoric focuses on the aesthetic powerfulness of tattoo art. The curators’ discourse echoes the Quai Branly Museum’s “polyphonic rhetoric” (Ventura, 2013) that became implemented and stabilized from the very start, dissociating art from science to better underline a pure aesthetic appreciation that would be fully accessible only to enlightened amateurs. Anne & Julien are certainly introducing themselves as “field journalists” and first‑hand observers of the transition of tattoo from “handicraft” to “artistic gesture”[11]. “Bookish knowledge” is thus compared with “real‑life experience” and authorizes the curators to speak up for a community they claim to belong to and share in their lifestyle. As a matter of fact, insiders (“great tattoo artists”) fully support their “mission”: to explain the truth about the artistic history of tattoo, which they root in the 19th century. During the 20th century, they produced various “artistic movements”. Tattoo styles defined by successive groups’ appropriation of the practice over time may then be ignored in favour of “pictorial schools” (the so‑called traditional, realistic, Japanese, tribal or abstractionist)[12].

Daily newspapers acknowledge the disjunction drawn by the invited curators. However, depending on the particular editorial policy, media coverage emphasizes either the “artification” of tattoo or its anthropological nature. In the article “Les tatoués au musée” (Le Monde, 27 July 2013), Stéphanie Lemoine observes the “rise of a new generation [of tattooists] less concerned about technical ability than self‑expression”. According to tattoo experts, true “artists” are a minority among what is still a “folk art”. Other national newspapers focus on the “several thousand‑year” history of a “universal” practice. Taking a postmodernist stance, Véronique Prat (“L’art à fleur de peau”, Le Figaro Magazine, 2 May 2014) talks about the personal meaning of body modification in relation to social dislocation, while Stéphanie Estournet (“Les tatoués, encre au musée”, Libération, 6 June 2014) describes with irony a “scientific” exhibition showing a lack of “pop spirit”.

The academic world both rejects and reinforces this divide, calling for tattooing to be examined as a “social marker” as well as a “graphic practice and a plastic art with its founding fathers, masters, “schools”, technical revolutions, and so on.” (Foreword to the workshops Le tatouage au prisme des sciences sociales et de l’histoire de l’art, 26‑27 September 2013). In that respect, the roles are clearly assigned and delineated by disciplinary boundaries of legitimacy. In the field of anthropology, which has a dominant position because of its long‑standing research tradition (Rolle & Galliot, 2022), there is the analysis of cross‑cultural distribution, production, circulation and appropriation of technical tools, images and uses of the practice. For art history, a field in which tattoo appears to be a challenging investigative subject due to its cultural vulgarity: examination of the crossover from a craft to an art form and the study of the figures, schools and period that had a strong imprint on the formation and succession of aesthetics. For sociology: specialized in social settings, the contemporary study of the social and cultural rehabilitation of the practice, its appropriation by a recomposed population and the professionalization of the field. In that prospect, barristers have only recently entered the debate to clarify the legal and fiscal status which applies to tattoo artists and their artworks based on present legal frameworks.

Stéphane Martin (former senior civil servant at the French Ministry of Culture and instrumental in the creation of the primary art museum Musée du Quai Branly where he was subsequently appointed director) there is more to the financing and hosting of a tattoo exhibition than this “second life as art” (linked to “renewed aesthetics”, “artistic movements” and “renowned artists”). He legitimates that tattoo comes under the museum’s umbrella through its popularity (20% of 25‑34 years old are tattooed nowadays according to a media poll), which is spread over various social spheres (fashion, design, advertisement, museums), and has the status of an ancestral custom (crossing cultures and times). Throughout the exhibition, the visitor is immersed in a historical and anthropological approach covering past and present uses of tattoo in Western, Asian and Oceania countries, with the artistic dimension provided by the commissioned tattooists’ work. Indeed, the creation ex nihilo of paintings on linen canvas, on the one hand, and of synthetic volumes reproducing body parts (torso, arms, legs), on the other, ensures the dissociation of the practice from a corporeal matter which always threatens to reduce it to a service industry[13].

There are three categories of tattooists that have accessed the museum space: historical tattoo figures (“pioneers” or “heroes of modern times”), undisputed skilled professionals in various tattoo styles (“masters of the art”) and innovators of new iconographic conventions (“visionary” tattooists). For example, tattoo flash designed by Sailor Jerry, a former US Navy conscript, is no longer just a reference offering standardized patterns to customers in tattoo studios. Such highly sought‑after collectables in the tattoo world – where commodities have not been systematically archived because of the practice’s daily, popular, hedonistic and dissenting roots – have become rare pieces of art when displayed in a museum. Their value is also based on their influence over generations of tattooists.

Similarly, contemporary tattooists who are copied by their peers appear as prominent figures by actively working towards the elevation of tattoo to art, and by embodying the attributes that give an artist their singularity (a particular trajectory, behaviour and lifestyle). This is the case of Paul Booth, an American second‑generation tattooist with art school experience (Kosut, 2013) and specialized in “dark” works. Booth’s “biomechanical” tattoo style and his applied technique of subtly shaded lines are inspired by Hans Ruedi Gyger’s airbrush paintings and “transhuman” artwork (Gyger designed the creature from Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien).

Lastly, a new generation of tattooists are entering the scene. Graduates of fine or applied art schools, they have joined the ranks of renowned practitioners, albeit to varied degrees of admiration because they challenge the prevailing figurative conventions of the most praised aesthetics in the tattoo domain. Yann Black (a French tattooist classically trained in illustration and animation) was the first recognized tattooist to deconstruct the elementary principles such as clear continuous lines, steady shading, sophisticated and realistic designs. Displayed in museums, his tattoo work is at the forefront of an “avant‑garde” movement. In the tattoo market he risks being labelled a “scribbler” (a bad drawer) as opposed to a “scratcher” (a bad tattoo machine handler), but he is also exposed to the stigma of the tattooist thinking of themselves as an “artist” as opposed to behaving like a “good tattooist” (by satisfying customers’ wishes with customized patterns) or a “tattoo artist” (by composing original designs) (Rolle, 2013).

Art boundaries have always been subject to negotiation, as shown by Michael Baxandall (1985 [1972]) with the case of Renaissance painters beginning to sign works and using arithmetic and geometrical rules to be attached to “liberal arts” instead of “applied arts”. Of course, such transition requires broader conditions of possibility. For instance, the recent entry of various popular cultures in established institutions responds to shifts that have occurred in the cultural field. The economic and ideological shift (art as “creative economy” oriented towards “cultural diversity”) in cultural policies from the 1980s onwards largely ushered in practices such as the exhibition of tattoo in museums. But it also triggered new managerial and entrepreneurial practices that gave rise to uncertainty and increased precariousness in cultural funding (increased dependence on private or own resources) and employment (growth of outsourcing to freelance workers). Furthermore, the access of popular practices to museums, far from levelling cultural hierarchies, remains restricted to institutions who are dominated in the art field. The legitimacy to propel the vulgar into cultural institutions thus entails distinguishing the prosaic from the refined. In turn, this strengthens the elevation of inner artistic and moral segmentation in the world giving new advantages to those who are already the most privileged. This small “elite” finally reproduces on the “plebeian” professional segments the cultural and social domination they used to decry because they are torn between preservation of the countercultural values defining its autonomy and claims for social respectability through their recognition as an art form that must take place in dominant social spaces, that is, in established cultural, mass media and academic institutions.

For this exhibition, the selected tattooists reflected distinctions in the tattoo market. As with industrial design (Dubuisson & Hennion, 1995), commercial success appears to be a prerequisite for gaining aesthetic complexity and freedom. “Tattoo artists” are thus able to collect new honours by entering museums. However, there is no guarantee that the most aesthetically skilful work will be displayed, as the selection process is complex, multifaceted and still needs to be thoroughly analysed. First, recognition depends on customers, peers and also influential intermediaries (specialized media, tattoo convention organizers) in the tattoo world. Second, matches are based on social and aesthetic affinities between the most highly praised tattooists and the cultural gatekeepers, whose social profiles have changed with recent shifts. The mechanisms of elective pairings bring into play qualities at the relational (ability to evolve in networks), cultural (artistic knowledge, aesthetic tastes), professional (skills, rules and work environment control) and broader social (commitment to moral values and to a lifestyle) level through familial socialization, educational training, professional career path and a larger social trajectory.

Indeed, the most socially skilled tattooists seem to have easier access to established reputation and museums. Gallery access is beyond the scope of this paper but the following point is worth noting: after launching their own gallery to temporarily sell work by “outsider pop artists” Anne & Julien developed partnerships, first with the online platform ArtJaws that is now exclusively specialised in digital art, and then with the Parisian gallery Arts Factory dedicated to graphic arts. The brand Hey! is organizing a special exhibition and sale at the Halle Saint‑Pierre’s Galerie du bas. In this sector, there are very few prominent figures who simultaneously produce, curate, comment on, promote and sell artworks, which reinforces the power of the few appointed “tattoo artists” in the service industry whose core activity is still tattooing. This accentuates the distinction between the renowned practitioners with long waiting lists and high street practitioners who rely on more day‑to‑day bookings. This contributes to the perception that the former as opposed to the latter are driven more by aesthetic than financial considerations, even though both make their living from the marketization of tattoo. In the end, the practitioners and intermediary actors who derive the most benefit from their position as multi‑positional players are leading successful companies with both financial profits and symbolic rewards in a “minor art world” (Becker, 1988 [1982]) in its initial stages of creation, which ultimately explains their domination in the field.

I wish to warmly thank Catherine Davies for her valuable English proofreading work.

Atkinson M., (2002), “Pretty in ink: Conformity, Resistance, and Negotiation in Women’s Tattooing”, Sex Roles, 47/5/6, 219-235.

Atkinson M., (2003), Tattooed. The Sociogenesis of a Body Art, Toronto: University of Toronto Press Inc.

Baxandall M., (1985), L’œil du Quattrocento. L’usage de la peinture dans l’Italie de la Renaissance (Traduit de l’américain par Yvette Delsaut), Paris : Gallimard.

Baxandall M., (1972), Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Becker H. S., (1988), Les mondes de l’art, (traduit de l’américain par Jeanne Bouniort), Paris : Flammarion.

Becker H. S., (1982), Art Worlds, Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Borja S., Sofio S., (2009), « Productions artistiques et logiques économiques : quand l’art entre en régime entrepreneurial », Regards Sociologiques, 37/38, 23-43.

Bourdieu P., (1996) [1979], La Distinction : critique sociale du jugement, Paris : Minuit.

Bourdieu P., (1984), Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (English translation by Richard Nice), Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bruno C., (2014), « Entretien avec Wim Delvoye. “Le seul portrait que je sais faire d’un être humain, c’est Cloaca” », Psychanalyse, 29/1, 117-129.

Caplan J. (dir.), (2000), Written on the Body. The Tattoo in European and American History. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

Cherbo Joni M., (1997), “Pop Art: Ugly Duckling to Swan”, in : Vera L. Zolberg, Joni M. Cherbo (dir.), Outsider art. Contesting boundaries in contemporary culture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 85-97.

Coulangeon P., Duval J. (dir.), (2013), Trente ans après La Distinction, de Pierre Bourdieu, Paris : La Découverte.

Darras E., (2012), « Un lieu de mémoire culturelle : le tuning », Sociologie de l’art, 21/3, 85-109.

DeMello M., (1995), “’Not Just for Bikers Anymore’: Popular Representation of American Tattooing”, The Journal of Popular Culture, 29/3, 37-52.

DeMello M., (2000), Bodies of Inscription. A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community, Durham: Duke University Press.

De Saint-Martin M., (2013), « La tentative de construction de l’espace social, d’“Anatomie du goût” à La Distinction. Quelques repères pour l’histoire d’une recherche », in : Ph. Coulangeon, J. Duval (dir.), Trente ans après La Distinction, de Pierre Bourdieu. Paris : La Découverte, 29-44.

Dubois V., (2009) [1999], La politique culturelle. Genèse d’une catégorie d’intervention publique, Paris : Belin.

Dubuisson S., Hennion A., (1995), « Le design industriel, entre création, technique et marché », Sociologie de l’art, 8, 9-30.

Fridman V., Ollivier M., (2004), « Goût, pratiques culturelles et inégalités sociales : branchés et exclus », Sociologie et Sociétés, 36/1, 3-11.

Friedman A., (2016), “Spectacle over Scholarship: Three Museum Tattoo Exhibits”, tattoohistorian.com, [Online], https://tattoohistorian.com/2016/10/20/spectacle-over-scholarship-three-museum-tattoo-exhibits/#more-544

Garcia M.-C., (2015), « La légitimation artistique de la danse hip-hop et du cirque contemporain, un effet de l’institutionnalisation de pratiques culturelles populaires », Informations sociales, 190/4, 92-99.

Gill R., Henwood K., McLean C., (2005), “Body Projects and the Regulation of Normative Masculinity”, Body & Society, 11/1, 37-62.

Golsenne T., (2013), « De l’infamie à l’élection. Le tatouage dans l’art contemporain », Journées d’études Le tatouage au prisme des sciences sociales et de l’histoire de l’art, INHA, Paris, 26-27 septembre 2013.

Heinich N., Shapiro R. (dir.), (2012), De l’artification. Enquêtes sur le passage à l’art, Paris : Editions de l’EHESS.

Irwin K., (2001), “Legitimating the First Tattoo: Moral Passage through Informal Interaction”, Symbolic Interaction, 24/1, 49-73.

Irwin K., (2003), “Saints and Sinners. Elite Tattoo Collectors and Tattooists as Positive and Negative Deviants”, Sociological Spectrum, 23, 27-57.

Jeanpierre L., Sofio S., (2009), Les commissaires d’exposition en France. Portrait social, rapport d’enquête remis à l’association Commissaires d’exposition associés.

Kosut M., (2006), “Mad Artists and Tattooed Perverts: Deviant Discourse and the Social construction of Cultural Categories”, Deviant Behavior, 27/1, 73-95.

Kosut M., (2013), “The Artification of Tattoo: Transformations Within a Cultural Field”, Cultural Sociology, 8/2, 142-158.

Lee Maroto M., (2011), “Professionalizing Body Art: A Marginalized Occupational Group’s Use of Informal and Formal Strategies of Control, Work and Occupations, 38/1, 101-138.

Lebois A., (2014), « Droit d’auteur et corps humain : le corps comme support d’une œuvre de l’esprit », in : C. Bernault, (dir.), Mélanges en l’honneur du professeur André Lucas. Paris : LexisNexis, 519-532.

Levine L. W., (2010), Culture d’en haut, culture d’en bas. L’émergence des hiérarchies culturelles aux Etats-Unis (Traduit de l’américain par Marianne Woollven et Olivier Vanhée), Paris : La Découverte.

Levine L. W. (1988), Highbrow/Lowbrow. The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Mauger G., (2013), « Bourdieu et les classes populaires. L’ambivalence des cultures dominées », in : Ph. Coulangeon & J. Duval (dir.), Trente ans après La Distinction, de Pierre Bourdieu, Paris : La Découverte, 243-254.

Mazé C., Poulard F., Ventura C., (2013), « Démantèlement, reconversions, créations. Contribution à l’analyse du changement institutionnel », in : C. Mazé, F. Poulard, C. Ventura (dir.), Les musées d’ethnologie. Culture, politique et changement institutionnel. Paris : Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 9-34.

Pasquier D., (2005a), « Penser la culture comme activité sociale », in : E. Maigret & E. Macé (dir.), Penser les médiacultures, Paris : Armand Colin/INA, 60-69.

Pasquier D., (2005b), « La “culture populaire” à l’épreuve des débats sociologiques », Hermès, 42/2, 60-69.

Poulard F., (2007), « Diriger les musées et administrer la culture ». Sociétés contemporaines, 66/2, 61-78.

Rolle V., (2011), « “Professionnels” et “artistes” sans l’être. La réglementation du métier de tatoueur », in : A. Ducret (dir.), A quoi servent les artistes ?, Zurich : Seismo, 61-83.

Rolle V., (2013), L’art de tatouer, Paris : Editions de la Maison des sciences de l’Homme.

Rolle V., (2016), « Les corps professionnels en jeu. Quand le tatouage révèle les hiérarchies des univers enquêté et enquêteur », Genèses. Sciences sociales et histoire, 104, 115-132.

Rolle V., (2020), « Le tatouage occidental : des marges vers la professionnalisation », in : M. Jaoul & D. Tharaud, Le tatouage & les modifications corporelles saisis par le droit, Montpellier/Limoges/Toulouse : Éditions l’Épitoge, 17-31.

Rolle V., Galliot S., (2020), “Body Modification”, The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, John Wiley & Sons, [Online], https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781118924396

Sanders C., (1989), Customizing the Body. The Art and Culture of Tattooing, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Siblot Y., Cartier M., Coutant I., Masclet O., Renahy N., (2015), Sociologie des classes populaires contemporaines, Paris : Armand Colin.

Vail D. A., (1999), “Tattoos Are Like Potato Chips… You can’t have just one: The Process of Becoming and Being a Collector”, Deviant Behavior, 20, 253-273.

Ventura Ch., (2013), « Les “polyphonies” du musée du quai Branly ou l’art d’acclimater les discours », in : C. Mazé, F. Poulard, C. Ventura (dir.), Les Musées d’ethnologie. Culture, politique et changement institutionnel. Paris : Editions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 71-100.

Anne & Julien, (2011), Hey ! Modern art & pop culture (Catalogue de l’exposition au Musée de la Halle Sant Pierre, Paris), Roubaix : Ankama Editions.

Breerette G., (2005), « Je cherche à donner une cotation à l’art », Le Monde, 25 août [online], http://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2005/08/25/wim-delvoye-je-cherche-a-donner-une-cotation-a-l-art_682535_3246.html

Estournet S., (2014), « Les tatoués, encre au musée », Libération, 6 juin [online], http://next.liberation.fr/arts/2014/06/06/les-tatoues-encre-au-musee_1035654

Gros de Beler A., (2014), Tatoueurs, tatoués, catalogue d’exposition, Paris : Musée du Quai Branly – Actes Sud.

Lemoine S., (2013), « Les tatoués au musée », Le Monde, 27 juillet, 3.

Musée du Quai Branly, (2014), « Tatoueurs, tatoués », Connaissance des arts. Hors-série, 624.

Perlein G., François R., (2010), Wim Delvoye, (Catalogue de l’exposition au Musée d’art moderne et d’art contemporain de Nice), Paris : Skira Flammarion.

Pierrat J., (2008), « Editorial ». Tatouage magazine, 65.

Prat V., (2014), « L’art à fleur de peau », Le Figaro Magazine, 2 mai, 66.

Richard D. D., Antonin Ch., (2013), Hey ! Modern art & pop culture (50 minutes). Les Instinctifs & C’est au Quatre, [online], https://vimeo.com/heylefilm

Sang Bleu, Antille E., (2008), Le Pavillon du Palais de Tokyo, (Catalogue d’exposition, SNEL) Belgique : Sand Bleu & Le Pavillon – Laboratoire de création du Palais de Tokyo.

Streckz P., (2007), Le devenir-cochon de Wim Delvoye, Bruxelles : Editions de la Lettre Volée.

Wolinski N., (2001), « Peintures sur soi », Beaux-Arts magazine, 203, 70-77.

[1].↑. For Michelle Lee Maroto (2011), even though industry insiders are generally against imposed professionalization, the lack of a trade union to defend the interests of the tattoo profession and its practitioners can be explained by the fact that inking practitioners identify as artists. In the French case, on the other hand, such self‑identification has been the driving force behind union struggles against the drastic regulation of tattoo studios. For example, the national tattoo artist trade union seeks the lower tax rate of 5.5% usually reserved for artists instead of the current 20% applied to service providers (Rolle, 2011).

[2].↑. See the contributions of Sarra Mezhoud and Alix Nyssen on this issue.

[3].↑. Monique de Saint‑Martin (2013), who worked closely with Pierre Bourdieu, highlights how the lack of survey respondents from working class categories hinders the provision of a refined statistical representation of popular tastes and lifestyles.

[4].↑. Vincent Dubois states that unlike the United States (followed by the UK), subsidization has not been fundamentally challenged in the French model. However, it is a shift that blurs the public‑private boundaries and at the same time pushes towards a greater partnership.

[5].↑. For Dominique Pasquier (2005b), Cultural Studies missed the opportunity to analyse the social influence of popular culture by overemphasising its oppositional purpose and autonomy, while Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of legitimacy neglected the bottom‑up diffusion of practices.

[6].↑. Besides the speech given by art historian Thomas Golsenne at the first French symposium on tattooing in 2013, various examples can be found in the artists‑in‑residence catalogue from the Pavillon (research laboratory) of the Parisian Palais de Tokyo, directed by Sang Bleu & Emmanuelle Antille (2008), as well as the article by art critic Natacha Wolinski published in a 2001 edition of Beaux Arts magazine. The author of the present paper ultimately chose to discuss the case of Jean‑Luc Verna.

[7].↑. As stated in a recent paper (Rolle, 2020), it is somewhat reminiscent of the French comedy Le tatoué (Denys de la Patellière, 1968) depicting the greed of a gallery owner (played by Louis de Funès) for a Modigliani work adorning the back of a penniless legionary (played by Jean Gabin). At the time, this seemed unlikely enough for a comedic plot. Audrey Dubois (2014) stresses that such an option is excluded by French case‑law dating from the beginning of the 1970s. “An individual may only choose to donate his body to science (and not to art), the “recipient” must use it for scientific or medical purposes as prescribed by law” (p. 528). The highly controversial and still internationally touring exhibition “Body Worlds” by German anatomist Gunter von Hagens has played on this ambiguity since the first exhibition in the mid‑1990s.

[8].↑. Translation of all quotations (from French to English) are the authors own. The list of Wim Delvoye interviews is too long to be cited here, but the interested reader may refer in particular to the article dated 25 August 2005 in French newspaper Le Monde.

[9].↑. In the book Le devenir‑cochon de Wim Delvoye, Pierre Streckx (2007) praises the artist for his ability to mix “the order of beauty from above with the horrors down below” in such a way that it produces the “vanguard of experimental art”. The subtlety of the artwork would thereupon only be discerned by an eclectic and informed eye. The texts published in the exhibition catalogue Wim Delvoy (2010) of the Nice Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MAMAC) relegate tattooing into a similar pigeonhole despite the respective political and postmodernist lens adopted on the practice.

[10].↑. In the introduction of the documentary Hey! Movie about Anne & Julien’s occupations between 2011 and 2012 (exhibition, art journal and alternative circus festival set up under the trademark Hey! and registered in 2009), Anne states: “We refuse the society in which we live. Let us be perfectly clear. We have all positioned ourselves intimately about it. It occurs that there are other people like us using different mediums expressing exactly the same thing. A love of singularity, a celebration of singularity, a prideness (sic) of living underground on the fringe, a way to perpetuate this statement but also a desire to communicate the respect due to those outsiders, because all of them in fact are warriors.” (Damien D. Richard & Christophe Antonin, 2013.) Besides that film, the following analysis is based on various oral and written data, notably: the talk given by freelance curators at the first French scientific symposium on tattoo organized in September 2013 by anthropologist Sébastien Galliot (scientific advisor of Tatoueurs, tatoués on Pacific and Oceanian tattoo), the Quai Branly accompanying exhibition catalogue (2014) and the special edition of the magazine Connaissance des arts (2014) as well as the media coverage of the event.

[11].↑. They both used to be columnists for various national and specialized mass media on an area of expertise covering counter‑cultural movements. Julien Deflisques notably worked as music programmer for nationwide radio France Inter.

[12].↑. In Anna Friedman’s (2016) critical points of view about the exhibition, the museum privileged a “blockbuster show” about popular culture “to get people in the door” over a scholar‑informed curatorial exhibition focusing “on design over content”. It was also sometimes grossly inaccurate about the history of Western tattoo.

[13].↑. The curators recycle the Guy le tatooer’s idea to tattoo silicone arms. Framed as a painting, the item intends to “champion the idea to represent the tattooist’s work in a different way” in the tattoo studio with the hope of stimulating “tattoo projects that the artist would love to complete” (Exhibition catalogue, Hey! Modern art & pop culture, 2011, 104).