Référence électronique

Chemmachery J., (2020), « The Mark of the Beast as Trace of History. Animalistic Tattoos in Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White (2002) and Kamila Shamsie’ Burnt Shadows (2009). », La Peaulogie 4, mis en ligne le 5 mai 2020, [En ligne] URL : https://lapeaulogie.fr/the-mark-of-the-beast-as-trace-of-history

The Mark of the Beast as Trace of History. Animalistic Tattoos in Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White (2002) and Kamila Shamsie’ Burnt Shadows (2009).

-

Description

Jaine CHEMMACHERY

Maître de conférences en études anglaises, laboratoire TransCrit, Université Paris 8 (EA1569).

Abstract

This article brings together two contemporary novels, Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White (2002) and Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows (2009). While the two novels deal with different topics, they share interesting common motifs. First, both engage with history. Secondly, both these novels highlight the presence of animal-related designs on their heroines’ skin. In Faber’s novel, Sugar, a prostitute, has marks on her skin which are reminiscent of tiger stripes. At the beginning of Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows, the heroine, Hiroko, is in Nagasaki with her German lover when the nuclear bomb strikes the area. As she recovers from the shock, the heroine, who was wearing a kimono with patterns representing cranes on it, finds herself branded with the very bird motifs onto her back. One may wonder what the branding of such designs stands for. Are such traces a way to suggest the violent impact of history on people, especially on these female characters? What differences may be drawn when it comes to assessing the effect of the “trace” in each case? The animal tattoos in both these novels may be seen as traces of history; yet the latter do not impact the heroines in similar ways.

Keywords

Postcolonialism, Neo-Victorian, tattoo, corporeality, history, trace, fiction

This article brings together two contemporary novels, one Neo-Victorian novel reconstructing Victorian characters and Victorian London from a contemporary perspective, and a novel which could be associated with Postcolonial studies as it tackles the story of a Japanese woman travelling from Japan to India and later to the US and discusses the impact of historical events upon her life trajectory, from World War Two to 9/11. While the two novels deal with different topics, they share common motifs. First, both engage with history. Indeed, The Crimson Petal and the White (2002) by Michel Faber, following Mark Llewellyn and Ann Heilman’s contention that what is Neo-Victorian is “self-consciously engaged with the act of (re)interpretation, (re)discovery and (re)vision concerning the Victorians” (Heilmann and Llewlellyn 2010, 4), engages with the history of Victorian England[1]. On the other hand, Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows (2009), by spanning 50 years and four geographical zones – Japan, the Indian sub-continent, Afghanistan and the US – engages with global history, geopolitics and terrorism. More peculiarly, both novels state the presence of animal-related designs on their heroines’ skin. In Faber’s novel, Sugar, a prostitute, is said to have marks on her skin which are reminiscent of tiger stripes. These animalistic traces are presented as symptoms of a skin condition which is similar to psoriasis. Yet, given Sugar’s profession, one could easily associate such marks with syphilis. Moreover, while many such diseases were spread to the colonies through white colonisers[2], Sugar’s name also recalls the woes of slavery in sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean.

At the beginning of Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows, the heroine, Hiroko, is in Nagasaki with her German lover, when the nuclear bomb strikes the area. As she recovers from the shock and realises that what is left of her lover is a mere shadow on a rock, Hiroko, who was wearing a kimono with patterns representing cranes on it, finds herself branded with the very bird motifs onto her back ; visual reminders of the trauma associated with Nagasaki.

It may be useful to conjure up Derrida’s concept of the trace, as at once linked to experience and separated from it, and as something which remains in the present: “wherever there is experience, there is trace, and there is no experience without a trace […] There is a trail, retention, protention, and so relationality to otherness, to the other, or to another time, another place, something that refers to the other ; there is trace”[3] (my translation). Hiroko’s bird patterns can be seen as traces of her experience of the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki by the US. They may also be considered as scars, if one considers that a scar is “a mark […] resulting from damage” or “a mark remaining (as on the skin) after injured tissue has healed”[4]. Arguably, Sugar’s marks result from her experience of ichthyosis, the skin condition which caused such traces to appear on her body. In both novels, the traces were caused by a past phenomenon[5]. According to Elizabeth Grosz, “The body is […] a point from which to rethink the opposition between the inside and the outside, the public and the private, the self and other, and all the other binary pairs associated with mind/body opposition” (1994, 21). The marks in the novels partake of a similar dialectics of visibility/invisibility as they are subjected in both cases to a male gaze. In regard to the animalistic traces, one may wonder what the branding of such designs stands for, alongside which conception of the body[6]. In Sugar’s case, the traces look like tiger stripes. To some extent, we may say that the disease had no particular intention of making these traces meaningful. They are made meaningful; first, on the diegetic level as they are submitted to the gaze of another character who interprets them, and ultimately they are by the narrative voice, and the authorial figure. In Shamsie’s novel, the traces are the transcriptions of the patterns that were on the garment Hiroko was wearing at the time of the bombing. So they do not consist in traces which were made to look like cranes, but are images of cranes printed upon the character’s skin, which in that respect likens them more to tattoos. Indeed, even if the tattoo was not “intentionally […] placed on the skin” (Merriam Webster’s definition) of Hiroko by history, it certainly was by Shamsie. Readers are thus made to interpret the patterns as being linked to animality, therefore to make sense of them as such. I will consider these patterns primarily as traces, and then as tattoos, using the term in its etymological meaning, i. e. “pigment design in skin”[7], because of the fact that their presence in the novels is linked to the authors’ intention of having us read them as reminiscent of cranes or tiger stripes. The animal traces, in both novels may be seen as traces of history, even if they do not impact the heroines in the same way. In Faber’s novel, the tiger stripes may suggest both Sugar’s savagery, in the eyes of her “owner”, and a history of exploitation and transgression, itself linked to colonisation and slavery. In Shamsie’s novel, the crane patterns evoke the transgenerational transmission of history, seen both as a burden and a curse.

Sugar’s tiger marks: a history of exploitation and transgression

In The Crimson Petal And The White, the reader learns about Sugar’s skin condition only a few pages after William Rackham, the son of a famous perfume industrial, has demanded exclusive patronage of the woman to Mrs Castaway, the madam of the brothel she works in. William Rackham found information on Sugar in “More Sprees in London – Hints for Men about Town, with Advice for Greenborns” (Faber, 2002, 83), a document which lists all the prostitutes to be found in London brothels. But the name Sugar redoubles the woman’s association with a commodity. Just as sugar was a commodity to be sold and exchanged for money, and was part of a system of exploitation of native resources and human workforce in the Caribbean through the triangular trade, the woman named Sugar in the novel has been exploited since she was 13 by her own mother who turned her into a prostitute, as well as by the many men who participated in the prostitution trade. Later in the book, William’s daughter, Sophie, reminds Sugar that her father “bought” her for her (Faber, 2002, 715), confirming the idea that Sugar is a commodity, an object associated with a certain amount of money, likely to be exchanged or sold to increase one’s capital.

This and the animal marks on Sugar’s skin tend to associate her with the figure of the (sex) slave, as slaves were themselves considered as animals. DeMello states:

African slaves were shackled and muzzled like animals, beaten like animals, branded like animals, and bought and sold like animals; they had their children taken from them like animals and had their humanity and individuality ignored, just as humans do with animals. They were property just as animals were, and could be legally killed by their property owner, just as animals could (DeMello, 2012, 265).

An articulation between capitalism and colonialism can be drawn as both have rested on the exploitation of certain bodies – those of humans who were reduced to the status of animal, and those of women[8]. The concomitance between capitalism and colonialism is suggested through the tiger stripes on Sugar’s skin. Indeed, despite her name recalling the colonies, Sugar is a white prostitute. Yet, in the novel, her having sexual intercourse with William Rackham, the son of an English entrepreneur, is a way to suggest the strong links between the sexual exploitation of women and consumer culture, and more generally, the affinities between capitalism, consumerism and colonialism.

Sugar’s animality: sugar’s criminality or the taming of the animal

Her skin is like nothing he’s ever seen: on every limb, and on her hips and belly, there are… what can he call them? Tiger stripes. Swirling geometrical patterns of peeling dryness alternating with reddened flesh. They are symmetrical, as if scored on her skin by a painstaking aesthete, or an African savage (Faber, 2002, 173)[9].

The reference to the tiger, along with William’s idea that the marks may have been made by an African savage, shows that there is a subtext that is alien to Victorian England. The references to the “African savage” and to the “geometrical” and “symmetrical” patterns suggest that the marks look as if they had been intentionally made on Sugar’s skin, therefore associated with some sense of agency, be it human (the African savage) or non-human (the disease)[10]. The image of the tiger conjures up other imaginaries. It suggests Sugar’s animality – at least, her animality as is phantasised by William: “to William, the patterns are beguiling, a fitting mark of her animal nature. She smells like an animal too: or what he imagines animals smell like, for he’s no animal lover” (Faber, 2002, p. 173). While the tradition of domesticating animals had been going on in Europe since the late 18th century, the revelation of William’s lack of knowledge of how animals smell conveys an interesting Orientalist touch to his perception of Sugar. By comparing the marks on her skin to tiger stripes, William turns Sugar into an Orientalist phantasy, one “to be feared […] or to be conquered” in Edward Said’s words (Said, 2003, 301), while he himself becomes an Orientalist producing his own phantasised image of animality/femininity. By associating Sugar with animality, William also partakes of a long-standing tradition which consisted in assimilating animality with criminality[11]:

The “criminal as animal” is a metaphor through which a person considered deviant is understood in terms of what are seen as the most negative qualities of certain kinds of animals [. . . ] “Beast” and its cognates took on connotations of the devil and evil and were increasingly used to denigrate what were seen as less worthier humans. These included women, ethnicized others, and criminals (cf. Hill 1971, 40 ; Thomas 1983, 43 ; and Fudge 2004, 17) (Olson 2013, 2)[12].

Sugar’s deviancy is shown in the fact she indulges into subversive sexual intercourse. As another prostitute explains to William, “Ain’t nuffink Sugar won’t do, sir. Nuffink. It’s common knowledge, sir, that special tastes as can’t be satisfied by the ordinary girl, Sugar will satisfy” (Faber, 2002, 74). Olsen notes: “Persistent prejudices about criminals […] rely on notions of their innate deviance and incorrigibility, their animal-like characters, and their visible otherness” (Olsen, 2013, 4; emphasis added). The tiger stripes are the visible traces of Sugar’s difference. Her criminal, deviant body is thus made visible, despite being legible, through its link with animality[13]. On the contrary, William is shown by the ironic narrator to be all but absolutely normal, if not boring: “his bouncing mop of golden hair was comical, but he was otherwise not very fascinating, especially compared to this woman you’re only just getting to know. But William Rackham is destined to be the Head of Rackham Perfumeries. Head of Rackham Perfumeries!” (Faber, 2002, 45). With the repetition and the exclamative mark, the narrator draws readers’ attention to a character which under any other circumstances would not have been deemed worthy of interest, i. e. the opposite of Sugar.

Sugar’s association with an animal makes her a criminal and a creature to be tamed. William, after having sex with Sugar, is described as being “able to examine his prize more closely” (emphasis added, 173), which recalls Orientalism’s conquest valence.

The fact that Sugar’s animality is printed upon her skin thus suggests her exploitable nature. It is fascinating to see that “interlinked systems of exploitation” (DeMello, 2012, 256) of women and animals have existed for ages. According to Margo DeMello:

Historically, women and animals have been considered less intelligent than men. Tactics such as objectification and ridicule have been and continue to be used to control and exploit women and animals. Women are called names such as cow, sow, pig, dog, bitch, fox, and hen; by symbolically associating them with animals, they are trivialized (DeMello, 2012, 262).

In the novel, Sugar is not associated with any of these animals but with the tiger and William repeatedly acknowledges her acute intelligence. This aims at showing that her femininity is an alternative to respectable Victorian femininity and is associated with wildness and power. But symbolic of (sexual) power as the animal may be[14], William sees himself as the hunter likely to exhibit his trophy as the term “prize” signals.

The image of the tiger also conjures up Asia and more particularly, India, the Jewel of the Crown, and by extension, the system of exploitation of resources that went along with the establishment of the Raj in India[15]. A hint at the underlying violence of colonisation, based on the exploitation of resources, both human and material, is visible in the phrases linked with Sugar’s marks such as “reddened flesh” and “scored on her skin”[16]. It is as if the marks had been the result of a process of voluntary branding on the skin of the English working-class woman, symbolically associated here with the Indian “subaltern”[17], by the capitalist system embodied by William Rackham. Her scarred flesh “re-enacts the embodied history of abused Victorian […] women” (Orr, 2017, 111), along with that of subalterns abused by the two-headed system of capitalism/colonialism while it bears witness to this history.

Such an association between body marks, violence and suffering can be found in at least another Neo-Victorian novel, The Essex Serpent (2016) by Sarah Perry. In the novel, Cora Seaborne used to be abused by her late husband. The correlation between tattoos, violence and suffering induced by a man’s printing his mark upon the female body is clearly made:

The neckline of her dress was a little lower than she’d have liked, and showed on her collarbone an ornate scar as long as her thumb, and about as wide. It was the perfect replica of the silver leaves on the silver candlesticks that flanked the silver mirror, and which her husband had pressed into her flesh as though he were sinking his signet ring into a pool of wax. She considered painting it over, but had grown fond of it, and knew that in some circles she was enviously believed to have had a tattoo (Perry, 2016, 16; emphasis added).

The repetition of the adjective “silver” alongside the reference to the ring connote metal while the image of the wax invites us to see Cora’s skin as malleable material that can be drawn upon. Only the use of the signet ring turns wax from material that does not signify into something meaningful. The scar/tattoo in The Essex Serpent echoes Grosz’s contention that “as well as being the site of knowledge-power, the body is thus also a site of resistance, for it exerts a recalcitrance, and always entails the possibility of a counterstrategic reinscription, for it is capable of being self-marked, self-represented in alternative ways” (Grosz, 1990, 64). The way Cora grows fond of the mark, as people consider it to be a tattoo[18] – something different than what it originally was – indicates that Cora’s mark is both a trace, that is what remains from a past event, and the origin of potentially new counter stories.

Sugar’s marks may be interpreted as the literal branding upon her flesh of the historical moment of concomitance between colonialism and capitalism which are often considered as male ventures and created their own oppressed and subaltern subjects based on race and/or gender. Just as her name epitomises how the exploitation of sugar partook of the capitalist enterprise, the marks reminiscent of tigers, hence of India, confirm the ineluctable relation between London and its colonies. Given the fact that Sugar’s marks are caused by a physical condition, one may venture to say that both capitalism and colonialism are likened to a disease which cannot be easily cured. Sugar repeatedly tries to use William Rackham’s cosmetic product “Crème de jeunesse” to erase the itching marks, yet to no avail.

The images of the tiger and the reddened flesh conjure up other images of violence perpetrated upon other animals, such as the branding of cattle. Sugar’s skin condition is called “ichthyosis” which also recalls ichthys, i. e. fish in ancient Greek; in other words, other animals. The rich animal imagery in the novel, along with suggestions of violence, hints at the intricated knot between capitalism and colonialism and at how the system rests on the exploitation of subaltern and/or animal lives.

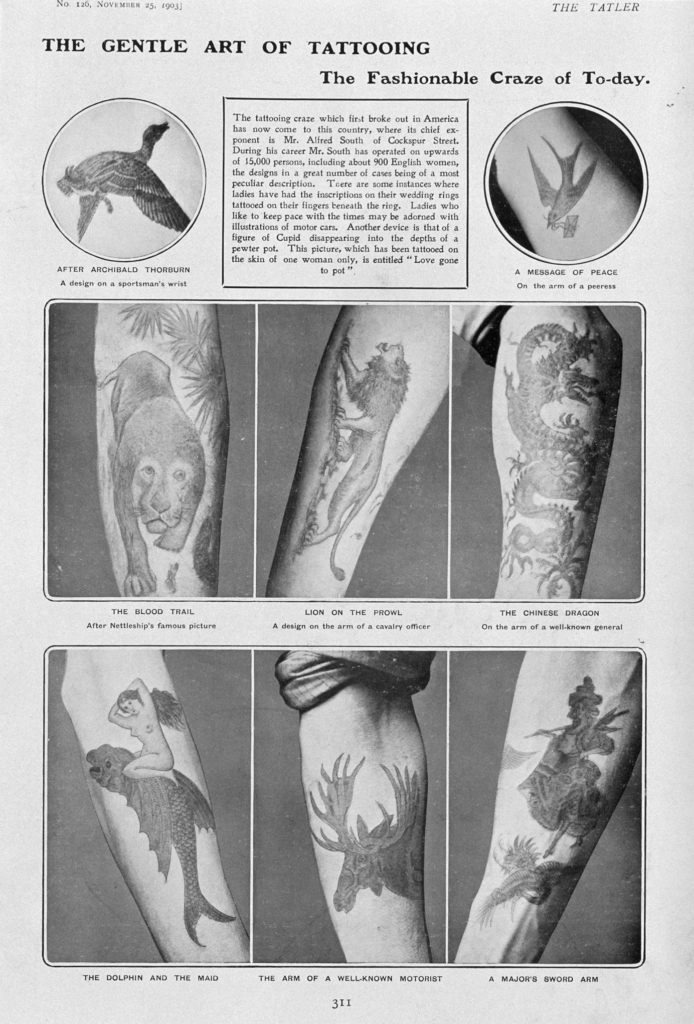

Taken from “The Gentle Art of Tattooing:The Fashionable Craze of Today”, from The Tatler and Bystander (1903).

Illustration found in James Bradley’s article “Body Commodification? Class and Tattoos in Victorian Britain” (Bradley, 2000, 149).Sens(ualis)ing the tattoo

In Shamsie’s story, the tattoo does not reveal itself at first glance. Its unveiling occurs progressively as the first chapter recalls the bombing of Nagasaki. It ends on the depiction of the heroine dressed in a kimono: “Her body from neck down a silk column, white with three black cranes swooping across her back” (Shamsie, 2009, 23). The bombing is not clearly named as it is perceived from Hiroko’s point of view even though the location and date presented as a subtitle for the first part of the novel “Nagasaki, 9 August 1945” leave no doubt to the 21st century reader as to the context in which the story unfolds. In parallel to terms confirming the event such as “fire and smoke” (Shamsie, 2009, 27), and the blatant formula “and then the world goes white” (Shamsie, 2009, 23), the writing echoes the confusion in the heroine’s mind:

Hiroko runs her fingers along her back as she climbs the stairs down which, minutes earlier, she had followed Konrad. There is feeling, then no feeling, skin and something else. Where there is skin, there is feeling. Where there is something else there is none. Shreds of what – skin or silk? She shrugs off the kimono. It falls from her shoulders, but does not touch the ground. Something keeps it attached to her (Shamsie, 2009, 26-27).

The heroine’s sense of confusion is paradoxically rendered by the recurrent use of the verb “be” which usually aims at asserting the existence of things; yet here, the verb is repeatedly used in parallel sentences which suggest the coexistence of contradictory elements. Confusion is also conveyed through the question “skin or silk?” which hints at uncertainty while the monosyllabic terms and the paronomasia highlight the fact that it is impossible to distinguish between the two types of material as skin is here assimilated to fabric[26]. Yet, the very violence of the event upon the body is underlined: “She touches the something else on her back. Her fingers can feel her back but her back cannot feel her fingers. Charred silk, seared flesh” (Shamsie, 2009, 27). The sentence “charred silk, seared flesh”, followed by “the touch of dead flesh”, gradually announces the “possibility of the tattoo”, as readers had earlier been told about the three cranes on Hiroko’s kimono.

It is only much later in the book, when Hiroko goes to Delhi to meet with the family of the man who should have become her husband, had the bombing at Nagasaki not occured, that the crane “tattoos” are unveiled. Hiroko, who used to work as a translator in Japan, falls in love with her Urdu teacher, who happens to be an employee of the Burtons, the family of her ex-lover. While Sajjad is about to have an arranged marriage, she acknowledges that the marks on her body will never enable her to marry:

She had stepped out of the shadow of the roof ’s overhang and into the harsh sunlight so there could be no mistaking the three charcoal-coloured bird-shaped burns on her back, the first below her shoulder blade, the second halfway down her spine, intersected by her bra, the third just above her waist. (Shamsie, 2009, 90-91)

Just as Faber’s text mentions the propensity of Sugar’s marks to be “diagrams for his [William’s] own fingers” (Faber, 2002, 309), Hiroko’s marks are given to Sajjad’s touch, yet in a more sensual description:

In a few quick steps he was next to her, his hands touching the space between the two lower burns, then pulling away as she shuddered. […] He touched the grotesque darkness below her shoulder blade – tentatively, fearfully – as though it were a relic of hell […] He closed his eyes and moved his hand to where the skin felt as skin should. (Shamsie, 2009, 91; emphasis added)

Later in the book, the burns on Hiroko’s back are explored by her son on a more playful note:

when he was a child he liked to sneak up behind me and tap against my back with a fork or a pencil, laughing when I carried on doing whatever I was doing, unaware. It made Sajjad so angry, but I was grateful he could approach it with such lightness. (Shamsie, 2009, 179)

The bird tattoos are motifs that are threaded throughout the story: they appear at regular instances in the novel as well as they generate tales, as the (not so) fairy tales Hiroko invents, should she once tell her son what happened at Nagasaki in August 1945:

There was the one about the girl whose dying father slithers towards her in the shape of a lizard ; she is so horrified by his grotesqueness it takes her years to understand that his final act was to come towards her, after a lifetime of walking away […] The one about the purple-backed book creatures with broken spines who immolate themselves rather than exist in a world in which everything written in them is shown to be fantasy. The woman who loses all feeling, fire entering from her back and searing her heart, so it’s possible for her to see a baby’s corpse and think only, There’s another one […] Monsters who spread their wings and land on human skin, resting there, biding their time. The army of fire demons, dropped from the sky, who kill with an embrace. […] The schoolteacher in a world where textbooks come to life ; she cannot escape from the anatomy text, its illustrations following her everywhere – bodies without skin, bodies with organs on display, bodies that reveal what happens to bodies when nothing in them works anymore (Shamsie, 2009, 177).

This rather long passage juxtaposes the many possible tales Hiroko could have told her son about the bombing at Nagasaki. The paratactic effect reflects the abundance of narratives that could emerge as an explanation for the scar tattoos on her back while the gruesome stories – implying unsettling images of distorted bodies, references to the bird tattoos as “monsters”, or words connoting death and extreme violence – precisely show that the tattoos, unpleasant as they may be to the heroine, can still be characterised by a productive power of their own. This could already be seen when Sajjad, first seeing the scar tattoos on Hiroko’s skin, said “birdback” (Shamsie, 2009, 91). Sajjad’s invention of a poetic, new noun to refer to the tattoos shows their productive power. The tattoo can thus lead its bearer to escape fixed significance or to invent new meaning. In both novels, readers are made to “feel” the tattoos in a writing connoting sensuality and materiality and to “make sense” of them. The fact that the crane tattoos move across generations in Shamsie’s novel particularly needs discussing as it may help us make even more sense of the tattoos.

The transgenerational power of the tattoos

The scar tattoos in Shamsie’s novel have a persistence that may be called “transgenerational”. It is all the more logical because in Japanese culture, the crane is a symbol of longevity; cranes were indeed said to have a life span of thousand years[27]. Even if Hiroko does not want people to believe she is haunted by her past, Shamsie’s text reveals a form of haunting. The branding in Shamsie’s novel is genetically transmitted as the recurring presence of the term “mark”, which is used to refer to Hiroko and Sajjad’s son, shows: as his mother was literally marked by the bomb, Raza comes to be seen in Pakistan as “a bomb-marked mongrel”(Shamsie, 2009, 191; 195) or the “boy marked by the bomb” (Shamsie, 2009, 207). The marking by history is thus transmitted through blood and operates as a sort of curse as the novel dwells on how history brought together the Burton and the Ashraf families throughout time and how tragic historical events have shaped the characters’ life trajectories. The word “mark” itself works as a trace that haunts Shamsie’s novel.

Kipling’s motif of the “mark of the beast” is present again, this time through the curse which has befallen the characters. But the reference to Kipling is also visible in the theme of intelligence which is one of the main topics of Kipling’s novel Kim (1901), while the characters travelling throughout the world in Shamsie’s novel are also reminiscent of the picaresque mode of Kim, yet often on a more tense and tragic note. Moreover, a direct reference to Kipling is present in the novel as one of the characters, albeit a female one, is called Kim. Kim’s father in the novel, explaining why he named his daughter so, says: “long before the CIA there had been Kipling and a boy astride a cannon” (Shamsie, 2009, 185), a direct reference to the first pages of Kipling’s novel.

Hiroko’s tattoos are all the more interesting because they seem to be alive, despite being paradoxically associated with death, at least in Hiroko’s mind. When she touches them for the first time, internal focalisation gives us access to her thoughts: “The touch of dead flesh. The smell – she has just located where the acrid smell comes from – of dead flesh” (Shamsie, 2009, 27). Hiroko is also shown to be repeatedly dreaming of them disappearing from her back and living inside her:

In the first years after Nagasaki she had dreams in which she awoke to find the tattoos gone from her skin, and knew the birds were inside her now, their beaks dripping venom into her bloodstream, their charred wings engulfing her organs.

But then her daughter died, and the dreams stopped. The birds had their prey.

They had returned through when she was pregnant with Raza – dreams angrier, more frightening than ever before […] But then Raza was born, ten-fingered and ten-toed, all limbs intact and functioning, and she had thought he’d been spared, the birds were done with her.

She had not imagined the birds could fly outwards and enter the mind of this girl, and from her mind enter Raza’s heart (Shamsie, 2009, 222).

Hiroko’s “tattoos” counter the Japanese assumption that cranes mean good luck. They convey here a sense of threat as they are endowed with a life of their own. The narrative voice in the passage associates the birds with verbs of action (“dripping venom”, “engulfing”) that are suggestive of ominousness. Their life-threatening dimension can also be seen in the fact that their influence exceeds Hiroko’s mind and body. Later, when she moves to New York, the birds prove more alive than ever: her back hurting, she interprets it as “a sign of her birds” displeasure that she should have chosen this, of all countries, as her place of refuge from a nuclear world” (Shamsie, 2009, 287). The distressful (lack of ) connection between Hiroko and her son is also blamed on the bird tattoos. It is as if the tattoos, by connecting mother and son, hindered communication between them. In one scene occurring towards the end of the novel, Hiroko and a character close to her quarrel, leading the narrative voice to comment: “The silence that followed was the silence of intimates who find themselves strangers. The dark birds were between them, their burnt feathers everywhere” (Shamsie, 2009, 362). While the connotation of the terms “dark” and “burnt” is here ostensibly negative, one wonders whether the birds, having a life of their own, do not also have an intentionality of their own that would be asynchronous with the characters’ intentions. If one considers that the birds, instead of being animals, are above all traces on Hiroko’s back, then they may be associated with things supposedly inert – mere images – yet characterised by what Jane Bennett calls “Thing‑Power”, that is “the curious ability of inanimate things to animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle” (Bennett, 2010, p. 6). Yet, the birds on Hiroko’s back do not act on their own: it is the fact they are on her skin and are linked to Nagasaki that makes them productive. Bennett’s words may be recalled again: “An actant never really acts alone. Its efficacy or agency always depends on the collaboration, cooperation, or interactive interference of many bodies and forces” (Bennett, 2010, 21). Both novels, through the scar/ tattoo motifs, ultimately complexify certain categories such as gender or race.

Complexifying history, making categories fluid

In a global history which has tended to present white people as unmarked and black people as having been marked by white people, in particular in the context of slavery, it is interesting to see Hiroko’s body as one that complexifies this history. Indeed, being a Japanese woman, her body is not one that has traditionally been seen as marked, as opposed to the bodies of black slaves or in completely different historical contexts, those of Maoris, Amazonian tribal groups, or even those of Jewish people in concentration camps. There is a subtle hint at the fact that Hiroko as a character disturbs categories in the novel: “James was oddly perturbed by this woman who he couldn’t place. Indians, Germans, the English, even Americans…he knew how to look at people and understand the contexts from which they sprang. But this Japanese woman in trousers. What on earth was she all about?” (Shamsie, 2009, 46).

Sugar’s tiger stripes and Hiroko’s tattoos can be seen as traces left by history on their bodies – respectively, the history of patriarchal violence alongside that of capitalism/colonialism, and the history of 20th-century America as a main global power. The marks on their skin also act as narratives of their selves; “a memoir in the flesh” (Beeler, 2007, 22). Still, it is interesting to see that both characters do not act the same in regard to the traces. Sugar’s marks, echoing what Putzi calls “the ineffaceable marks of the system” (Putzi, 2006, 109), will not be erased despite the heroine’s efforts to make them disappear. Hiroko’s marks are simply not to be erased. On the contrary, she seems to abide by their influence in an attitude of passive obedience; the traces on her body act as “silent marker and a site of trauma” (Beeler, 2007, 183). According to the heroine, the mark of the tattoos is what accounts for Raza’s behaviour as he, by way of the curse, cannot escape them. As was recalled earlier, Hiroko tried to protect her son from “them” by inventing fairy tales about the tattoos and Nagasaki which she never in the end told him but according to Hiroko, the birds entered her son’s head anyway. The traces left by Nagasaki on Hiroko’s body have a fatal dimension to them; their presence is not without recalling fatum in Greek tragedies. Still, in both cases, the traces simultaneously determine the characters’ identity – Sugar as a prostitute having a body that differs, and is made different, from the bodies of other women and that carries, indirectly, the history of the concomitance between capitalism and colonialism ; Hiroko as a direct victim of a traumatic historical event, the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki in August 1945.

Yet, their stories also illustrate how they escape, even resist, definite designation and circulate across fluid categories. Sugar upsets at least definitions of gender and class by being both a prostitute and a writer-to-be in Victorian England. Hiroko, by being a Japanese woman married to an Indian forced to move to Pakistan, upon arrival in New York in the years 2000 explains to a taxi driver: “I’ve lived in Pakistan since “47 […] I am Pakistani.” (Shamsie, 2009, 288). The crucial historical event which occurred in 1945 in Japan and the resulting tattoos branded on her skin have made her identity multiple and fluid, not easy to grasp. The traces on the two characters’ bodies are traces of history as well as canvasses for how they are socially positioned but also ways of inscribing the narrative of their selves-in-progress. Both novels depict a fluidity or porosity between the tattoo and the scar. As Putzi puts it, the tattoo “may initially appear to fix identity, marking it forever in the flesh, but it can also be seen as a symbol of fluid identity boundaries resisting any definitive interpretation” (Putzi, 2006, 26).

After analysing the echoes but also the differences between Sugar’s and Hiroko’s traces, it remains to be seen whether the common motif of animality can be further made sense of. Here is what can be said for the moment. Akira Mizuta Lippit argued in 2000 that the industrialisation of the West occurred alongside humans developing a cultural blindness towards animals. From this premise, Ann-Sofie Lönngren invites us to see “the convention of reading animals metaphorically and thus as “really” representing aspects of the human”(Lönngren, 2015, 16) as part of a similar process. Lönngren adds insightfully:

Although it is, as a member of the species Homo Sapiens, of course impossible to escape the anthropocentric worldview altogether, it is certainly possible to question the centrality of “the human” in the humanities, to point out the consequences of this bias, and to employ theoretical concepts and methods according to which more-than anthropocentric knowledge can be produced (Lönngren, 2015, 22).

As Faber’s novel has been characterised by George Letissier as a Neo-Victorian classic, the motif of the tiger stripes surely partakes of Neo-Victorianism’s tendency to consider the past from a present perspective and to provide a metatextual outlook on some of the ideologies or discourses that were prevalent in Victorian England, in particular on race or gender. These two texts certainly invite us to see the tattoo as not just an indication of moral character in Sugar’s case or a curse in Hiroko’s: rather than mere tropes, they become empowering images that enable us to think of how women “claim their own bodies and the experiences they represent” (Putzi, 2006, 98). But the very fact that Hiroko’s bird tattoos should be endowed with a life of their own performs maybe something of a different nature, calling scholars’ attention to the necessity to consider “animal representations as signifying “actual” animals, of different kinds and with their own potential agencies and interests” (Lönngren, 2015, 22); in other words, the crane tattoos may be an invitation to seek less to interpret animal traces as being necessarily meaningful or significant to humans and to literally follow “the “tracks” left by animals in the text” (Armstrong, 2008, 3) to help us think of alternative forms of agency and of being in the world.

Références bibliographiques

Arias R., (2014), “Traces and vestiges of the Victorian past in contemporary fiction”, In: Boehm-Schnitker N., Gruss S. (Eds.), Neo‑Victorian literature and culture: Immersions and revisitations, Londons, New-York: Routledge, 111-122.

Armstrong P., (2008), What animals mean in the fiction of modernity, Londons, New-York : Routledge.

Beeler K., (2006), Tattoos, desire and violence: Marks of resistance in literature, film and television, Jefferson, North Carolina, London: McFarland.

Bennett J., (2010), Vibrant matter, Durham: Duke University Press.

Bradley J., (2000), “Body commodification? Class and tattoos in Victorian Britain”, In: J. Caplan (ed.), Written on the body: The tattoo in European and American history, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 136-155.

Buchinger G., (2009), Burning bright: The tiger in Anglophone literature, Tectum Verlag.

Caplan J., (2000), Written on the body: The tattoo in European and American history, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Derrida J., (2014), Trace et archive, image et art. Suivi de Hommage à Jacques Derrida by Bougnoux D., Stiegler B., Bry s/Marne : INA Éditions.

DeMello M., (2012), Animals and society: An introduction to human‑animal studies, New-York : Columbia Uni Press.

Faber M., (2002), The crimson petal and the white, Edimburg, London: Cannongate.

Grosz E., (1990), “Inscriptions and body-maps: Representations of the corporeal”, In: Threadgold T., Cranny-Francis A. (Eds.), Feminine/Masculine and representation, Allen & Unwin, 62-74.

Grosz E., (1994), Volatile bodies: Towards a corporeal feminism, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Heilmann A., Llewellyn M., (2010), Neo‑Victorianism. The Victorians in the twenty‑first century, 1999‑2009, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kipling R., (1987), “The Mark of the beast”, Life’s handicap, 1891, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lippit A. M., (2000), Electric animal: Toward a rhetoric of wildlife, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1-26.

Lönngren A-S., (2015), Following the animal: Power, agency, and human‑animal transformations in modern, Northern‑European literature, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars.

Miller J., (2012), Empire and the animal body, London: Anthem Press.

Mulvey L., (1975), “Visual pleasure and narrative cinema”, In: Braudy L., Cohen M. (Eds.), Film theory and criticism: Introductory readings, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 833-844.

Olson G., (2013), Criminals as animals from Shakespeare to Lombroso, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

Orr A., (2017), “Inked in: The feminist politics of tattooing in Sarah Hall’s The Electric Michelangelo”, Neo‑Victorian Studies, 9/2, 97-125.

Perry S., (2018), The Essex serpent, 2016, New-York: Custom House.

Putzi J., (2006), Identifying marks: Race, gender, and the marked body in 19th century America, Athen: University of Georgia Press.

Said, E., 1978, Orientalism, (2003), New-York: Vintage Books.

Schell, H., (2007), “Tiger Tales”, In: Denenholz Morse D., Danahay M. A. (eds.), Victorian Animal Dreams: Representations of Animals in Victorian Literature and Culture, Hampshire: Ashgate, 229-248.

Shamsie, K., (2009), Burnt Shadows, London, Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Vergès F., (2017), Le Ventre des femmes : Capitalisme, racialisation, féminisme, Paris, A. Michel.

[1].↑ Right from the incipit, a tantalising narrator, using the “you” pronoun to speak to us, 21st century readers, reminds us that we are from different time and space than the characters of the novel: “Watch your steps. Keep your wits about you; you will need them. This city I am bringing you to [London] is vast and intricate, and you have not been here before. You may imagine, from other stories you’ve read, that you know it well, but those stories flattered you, welcoming you as a friend, treating you as if youa belonged. The truth is that you are an alien from another time and place altogether” (Faber, 2002, 3).

[2].↑ The article published by Heather Pringle, “How Europeans brought sickness to the new world” (Science, 2015). https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/06/how-europeans-brought- sickness-new-world Last retrieved on February 28th, 2020.

[3].↑ « Partout où il y a de l’expérience, il y a de la trace, et il n’y a pas d’expérience sans trace. […] Il y a du sillage, de la rétention, de la protention et donc du rapport à de l’autre, à l’autre, ou à un autre moment, un autre lieu, du renvoi à l’autre, il y a de la trace » (Derrida, 2014, 59).

[4].↑ Definition of the Merriam-Webster dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/ dictionary/scar February 28, 2020.

[5].↑ One may recall that the etymology of “trace”, a “track made by the passage of a person or thing”, comes from old French (12th century) in which it meant “mark, imprint, tracks” https:// www.etymonline.com/word/trace February 28, 2020.

[6].↑ Jane Caplan recalls that “tattooing alone has had an extended, if discontinuous history in Western culture. At the same time, it has occupied an uneasy and ambiguous status within a dominant culture in which body-marking was usually treated as punitive and stigmatic rather than honourable or decorative” (Caplan, 2000, xi).

[7].↑ https://www.etymonline.com/word/tattoo February 28, 2020.

[8].↑ Vergès F., (2017), Le Ventre des femmes : Capitalisme, racialisation, féminisme, Paris, A. Michel.

[9].↑ The narrative voice later evokes the “tiger textures on her skin like diagrams for his [William’s] own fingers” (Faber, 2002, 309), reinforcing the notion of compatibility or correlation between capitalist England and prostitution/consumerism.

[10].↑ This reminds us of the question the political theorist Jane Bennett asks in Vibrant Matter: “How would political responses to public problems change were we to take seriously the vitality of (nonhuman) bodies? By “vitality’ I mean the capacity of things […] to act as quasi agents or forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own” (Bennett, 2010, viii).

[11].↑ The way some criminals – sexual predators or terrorists – are referred to as “beasts” or “monsters” shows how vivid the metaphor still is in the 21st century.

[12].↑ In his article “Body Commodification? Class and Tattoos in Victorian Britain”, James Bradley highlights that “by the end of the nineteenth century tattoos had increasingly become associated with criminals” (Bradley, 2000, 137). Sugar’s tiger stripes thus doubly mark her as a criminal: she is tattooed and she shares a link with animality.

[13].↑ Earlier in the novel, her friend Caroline wonders if it is Sugar’s “animal serenity” (Faber, 2002, 29) that men find so attractive about her. Her animality, though imagined from a different perspective, is again what makes Sugar different from other prostitutes.

[14].↑ Tigers used to be associated in Ancient China with yin and with sexual power: “This sexual connotation [of the tiger] goes back to early Asian beliefs. […] It was adopted by the British during colonial times and gave the tiger’s pelt an air of lasciviousness and sensuality” (Buchinger, 2009, 22).

[15].↑ The tiger hunt was a fashionable sport in British India: “the practice of shooting tigers became a rite of passage that led to the almost obligatory inclusion of the description of tiger kills in the memoirs of many Englishmen in India” (Buchinger, 2009, 19-20).

[16].↑ Later in the novel, the ichthyosis patterns are said to “radiate […] like scars from a thousand flagellations, but in perfect symmetry, as though inflicted by a deranged aesthete” (Faber, 2002, 198; emphasis mine).

[17].↑ The term is used in the context of Ranajit Guha’s “Subaltern Studies”. It refers to those who have been subjected to colonialism and who still face the epistemic violence of Western thought frames. These studies aim at suggesting the possibility of having alternative historical narratives written “from below” and for the subaltern subjects, the possibility of being empowered.

[18].↑ Tattooing at the end of the 19th century was not only associated with criminals or sailors. As Bradley shows, “at some time around the late 1880s fashionable society was gripped by a tattoo craze” (Bradley, 2000, 145-146) with several texts stating that wealthy Londoners had their bodies tattooed. This explains why Cora Seaborne feels proud that some people should consider the trace of her husband’s assaulting her as a recently acquired tattoo.

[19].↑ “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split into active/male and passive/female… In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneousy looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to‑be‑looked‑at‑ness” (Mulvey, 1975, 47-48).

[20].↑ William also “imagines himself as a restless beast […] His lust suggests ever more vivid fantasies of sexual conquest and revenge. By turns, he rapes the world into submission, and cowers under its boot in piteous despair – each time more ferocious, each time more fawning” (Faber, 2002, 67). The lexical field of bestiality (“ferocious”) is associated with that of violence made to women (“sexual conquest”, “rapes”) and of slyness as well. The use of omniscient narration gives interesting information about William’s persona which readers would not have access to, were William the sole focal point.

[21].↑ Had William been more able to read the marks, he could have recognised the tiger as “a metaphor of insurrection in the British mythology of power” (Miller, 2012, 40) and possibly anticipated Sugar’s behaviour at the end of the novel. It is also possible to interpret the fact that Sugar’s marks are associated with the (Indian) tiger by William Rackham as a sign pointing to what he will later consider as her slyness (as opposed to the British lion, to which he may identify more). Similarly, in Kipling’s Jungle Books, even if the tiger is called Shere Khan – with the latter word being suggestive of domination, the tiger is not that respected by other animals, possibly because of its crippled appearance. Shere Khan was born with a lame hind leg which got him the nickname of “Lungri”, the lame one.

[22].↑ Still, even the doctor’s knowledge is questioned when the narrator adds: “He might prescribe expensive ointments which would have no more effect on the cracks in Sugar’s hands or the flaky stripes on her thighs than the cheap oil she’s already using” (Faber, 2002, 173).

[23].↑ Later in the novel, Sugar is shown to be scratching at her forearms “until her skin is the texture of grated ginger-root” (Faber, 2002, 284). The reference to ginger here again connects Sugar with exoticism.

[24].↑ “Tigers were often contrasted favorably to panthers: “‘The tiger is, as a rule, a gentleman. The panther, on the other hand, is a bounder,’ Glasfurd asserted […] Many authors alluded to the tiger’s ‘nobility’” (Schell, 2007, 242)

[25].↑ At the end of the novel, Sugar escapes with Sophie, William’s daughter, but in the process, all the pages she had written for her novel end up flying in the air, spreading her words in the posh area of London where William is living. Even if this could be interpreted as her message of female empowerment spreading beyond the scope of her potential novel, the fact she does not ultimately become a writer qualifies the extent of her final emancipation.

[26].↑ Sugar’s marked hands are once referred to as “leathery palms” (Faber, 2002, 36).

[27].↑ https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2015/08/28/how-paper-cranes-became-a-symbole-of- healing-in-japan/ Last retrieved on February 28th, 2020.