Référence électronique

Matthews David A. (traduit par Ricordel I., Couturier M.), (2019). « Techniques toxiques. Chapeaux mercuriels », [En ligne] La Peaulogie 3, mis en ligne le 18 décembre 2019, URL : https://lapeaulogie.fr/techniques-toxiques-chapeaux-mercuriels

Techniques toxiques. Chapeaux mercuriels

-

Description

Alison MATTHEWS DAVID

Associate Professor

School of Fashion, Faculty of Communication and Design

Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 2K3traduction Ivan RICORDEL, Myriam COUTURIER

Cet article a été réimprimé avec l’autorisation de Bloomsbury Publishing. Il s’agit d’une version légèrement révisée et traduite d’un chapitre intitulé « Toxic Techniques: Mercurial Hats », in Fashion Victims. The Dangers of Dress Past and Present, Alison MATTHEWS DAVID, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015, pp. 42-71.

Le musée des Moulages de l’Hôpital Saint-Louis à Paris abrite des murs entiers de vitrines renfermant des moulages en cire reproduisant les maladies de peau dont sont affectés les pauvres de la capitale mondiale de la mode. Ils sont d’un réalisme saisissant.

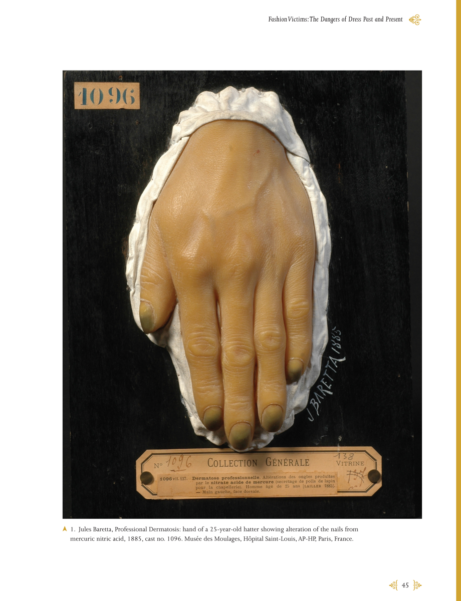

Le musée a été fondé dans les années 1860. Son but est d’aider les médecins à enseigner à une nouvelle génération de dermatologues grâce à des moulages peints à la main et faits directement à partir de corps de cas cliniques vivants. Le moulage fantasmagorique réalisé par Jules Baretta montre un jeune chapelier de 25 ans souffrant d’une maladie dermatologique professionnelle : « La modification des ongles produit par l’acide nitrique mercuriel » (Fig. 1). Moulé en 1885, les ongles de ce jeune homme avait été teints en permanence par les produits chimiques toxiques utilisés pour transformer la fourrure brute en chapeaux pour hommes à la mode. Cette coloration prouve que ce chapelier ne portait pas de gants de protection, ce qui a permis la pénétration systémique du poison directement à travers la peau. Mais cette main révèle également que le chapelier, trop pauvre sans doute pour consulter un médecin privé, s’est probablement rendu à l’hôpital public gratuit parce qu’il était déjà malade. Ses ongles se présentent en forme de massues légèrement bombées caractéristiques de l’hippocratisme digital correspondant à une privation d’oxygène. Cet hippocratisme digital aurait pu provenir d’une maladie pulmonaire courante chez de nombreuses personnes, d’une maladie cardiaque préexistante ou découlant de son travail avec du mercure. L’exposition au mercure en soi peut être à l’origine de cette affection, et il est clair qu’à 25 ans, le métier de ce jeune homme avait déjà laissé des traces indélébiles sur ses mains et sa santé[1].

Fig.1 Jules Baretta, Dermatose professionnelle : main d’un chapelier de 25 ans montrant une modification des ongles produite par l’acide nitrique mercuriel,

1885, moulage no. 1096. Musée des Moulages, Hôpital Saint-Louis, AP-HP, Paris, France.Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

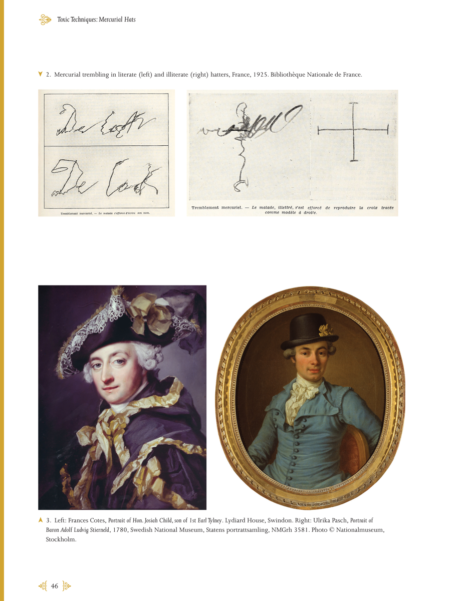

D’autres mains endommagées sont présentées dans une étude réalisée en 1925 par le Bureau International du Travail (Fig. 2). Ce rapport montre comment le mercure altère le système neuromoteur. Des lignes tracées au crayon, griffonnées, soulignent le tremblement incontrôlable des chapeliers de nationalité française qui essaient de signer leur nom. En Amérique du Nord, ces mouvements involontaires étaient appelés les hatters’ shakes ou Danbury shakes[2]. La signature examinée est le fait d’un chapelier empoisonné, à peine capable de signer son nom « De Cock », tandis qu’un autre, illettré, a remplacé son nom par une croix. En France, pays qui a légiféré en 1882 pour un enseignement gratuit, universel et obligatoire, ce gribouillage à peine lisible témoigne du fait que la fabrication de chapeaux était passée du stade de l’artisanat à une production mécanique en usine. Au début du XXème siècle, les hommes plus âgés, moins éduqués ou immigrés pratiquaient ce métier salissant, poussiéreux et meurtrier.

Ce chapitre traite de la mode masculine et de l’empoisonnement chronique au mercure qu’elle a causé, dévoilant la terrible réalité cachée derrière des icônes culturelles très appréciées telles que celle de l’excentrique Mad Hatter (chapelier fou) de Lewis Carroll d’Alice au pays des merveilles.

Fig.2 Tremblements mercuriels chez un chapelier instruit (gauche) et analphabète (droite),

France, 1925. Bibliothèque nationale de France.Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

Fig.3 À gauche: Frances Cotes, Portrait de l’honorable Josiah Child, fils du 1er comte Tylney. Lydiard House, Swindon. À droite: Ulrika Pasch, Portrait de Baron Adolf Ludvig Stierneld,

1780, Swedish National Museum, Statens portrattsamling, NMGrh 3581. Photo © National museum, Stockholm.Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

Styles Protéens

« J’ai vu des chapeaux dans ma jeunesse qui avoient de très grands bords ; et quand ils étoient rabattus, ils ressembloient à des parapluies : tantôt on releva, tantôt on rabaissa les bords par le moyen des gances. On leur a donné depuis la forme d’un bateau. Aujourd’hui, la forme ronde et nue paroît la dominante ; car le chapeau est un Protée qui prend toutes les Figures qu’on veut lui donner. »

Louis Sébastien Mercier, « Chapeaux », Tableau de Paris, vol. IV, 1782, 62.Dans sa description de Paris, Mercier évoquait les styles de coiffures masculines en constante évolution. Il avait expérimenté des formes de chapeau aussi changeantes que le dieu de la mer grecque Protée (ou Prôteús). Dans les années 1750, années de la jeunesse de Mercier, ces chapeaux eurent de larges rebords qui pouvaient être levés ou baissés ; plus tard, ils ont pris une forme de bateau appelée bicorne ; et au début des années 1780, une couronne ronde à bord étroit était à la dernière mode.

Les chapeaux de la fin du 18ème siècle étaient protéiformes. Le mercure était littéralement incrusté dans les touffes de poils utilisées pour fabriquer les chapeaux à la mode. Bien que ses effets nocifs soient connus, il s’agissait du moyen le moins coûteux et le plus efficace pour transformer une fourrure dure et de qualité inférieure provenant de lapins et de lièvres, en feutre malléable. Le feutre est un tissu non tissé qui peut être fabriqué à partir d’une grande diversité de matières premières, y compris les matières synthétiques[3]. Si la laine peut être collectée sans nuire à l’animal, le feutre de fourrure provient de sa peau. Et presque n’importe quelle bête faisait l’affaire : « Pour ce qui est du feutre de fourrure, si elle avait quatre pattes et de la fourrure – et si elle passait devant un magasin de chapeaux – elle était utilisée dans un chapeau[4] ». Afin que les poils forment un tissu résistant, ils devaient être retirés de la peau et « feutrés » ou enchevêtrés par une combinaison de frottement, de pression, d’humidité, de produits chimiques et de chaleur. En appliquant une solution acide et mercurielle sur les peaux, les protéines de la kératine présentes dans les poils sont décomposées et leur couleur devient orange rougeâtre, d’où le terme technique « carroting », comme une carotte en anglais, ou secrétage en français[5].

Comme les chapeaux qu’il a contribué à produire, le mercure, avec ses perles argentées et brillantes, est une substance magnifique, modifiable et qui change de forme[6]. Pourtant, sa surface brillante est trompeuse : avec le plomb, le mercure est l’une des substances les plus dangereuses pour la santé humaine et peut être facilement absorbé par les poumons et, dans une moindre mesure, par la peau ou l’estomac. Cependant, contrairement aux tendances de la mode touchant aux formes des chapeaux, rapidement disparues, le mercure est persistant. Une fois dans le corps d’un chapelier, le tissu d’un chapeau, ou le sol près des usines de fabrication de chapeaux, le mercure y est pour toujours[7].

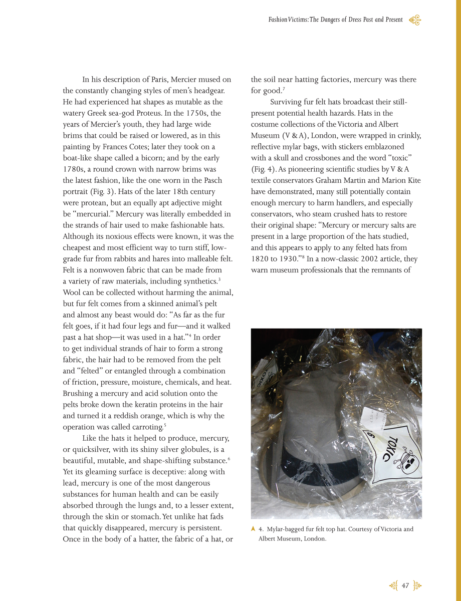

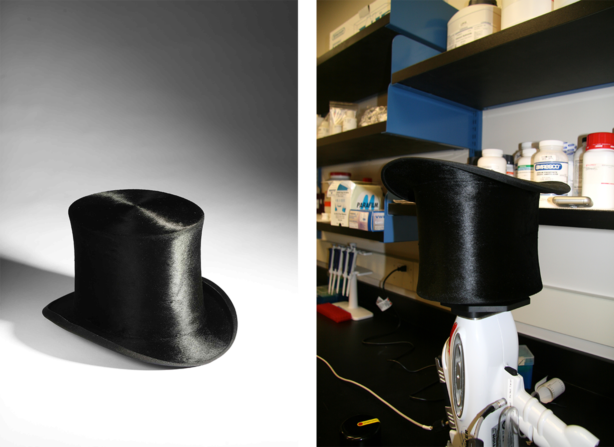

C’est pourquoi aujourd’hui les chapeaux de fourrure conservés diffusent toujours leurs dangers potentiels pour la santé. Ceux des collections de costumes du Victoria and Albert Museum (V & A), à Londres, sont enveloppés dans des sacs en mylar réfléchissants et plissés, avec des autocollants ornés du logo représentant un crâne avec os croisés et du mot « toxique » (Fig. 4) Comme l’ont démontré des études scientifiques pionnières menées par les conservateurs du textile du V & A, Graham Martin et Marion Kite, beaucoup contiennent encore suffisamment de mercure pour nuire aux manipulateurs, et plus particulièrement aux « conservateurs de textiles » qui cuisent à la vapeur des chapeaux écrasés pour leur faire retrouver leur forme d’origine : « Le mercure ou ses sels sont présents dans un grand nombre des chapeaux étudiés, et cela semble s’appliquer à tous les chapeaux feutrés de 1820 à 1930[8] ». Dans un article désormais classique, publié en 2002, les auteurs préviennent les professionnels des musées que les restes de mercure provenant du processus de secrétage demeurent toujours une menace[9]. Parce qu’ils pensent que jusqu’à 50% de leurs chapeaux en feutre de fourrure peuvent contenir du mercure, ces professionnels les ont tous emballés à titre préventif[10].

Fig.4 Chapeau haut-de-forme en feutre de fourrure enveloppé dans un sac mylar. Avec la permission du Victoria and Albert Museum, Londres.

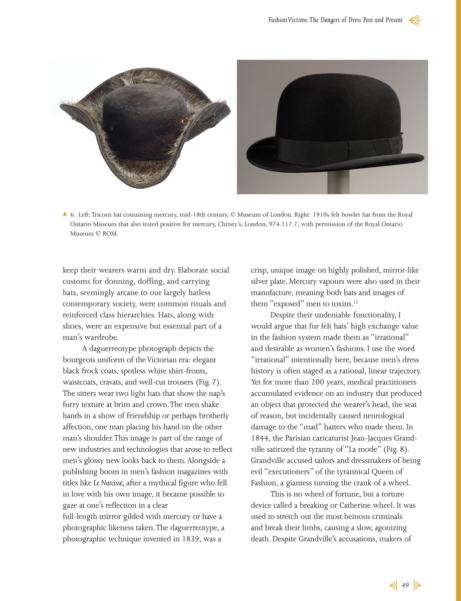

Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par BloomsburyPlusieurs conservateurs de musées ont généreusement analysé pour nous des artefacts de leurs collections en utilisant des techniques similaires. Ils ont utilisé des appareils portables de spectrométrie de fluorescence X (XRF), méthode analytique permettant de déterminer dans un objet, la présence de métaux lourds comme le plomb et le mercure, ainsi que d’autres toxiques, dont l’arsenic (Fig. 5). Des tests effectués au Royal Ontario Museum/Musée Royal de l’Ontario (ROM), au Museum of London et au département de physique de l’Université Ryerson ont révélé la présence de mercure dans un nombre substantiel de chapeaux dont un tricorne de « pirate », datant probablement du milieu du XVIIIème siècle, soit quelques décennies seulement après l’introduction du mercure dans les années 1730, ainsi que des chapeaux du début du XXème siècle au ROM (Fig. 6)[11]. Face à des preuves médicolégales irréfutables montrant que les chapeaux de fourrure dans les collections de musées sont encore toxiques aujourd’hui, notre étude cherche à répondre aux questions importantes suivantes : comment les chapeaux provoquent-ils une intoxication au mercure ? Comment cela affecte-t-il la santé des chapeliers ? Et pourquoi le problème est-il si persistant ?

Fig.5 Chapeau en feutre de fourrure datant de la fin du 19ème siècle (photo gauche) de la collection du Bata Shoe Museum placé dans une machine portative en vue d’une analyse XRF (photo droite)

au laboratoire de physique du professeur Ana Pejović-Milić. L’analyse fut effectuée par Eric Da Silva de l’université Ryerson. Le chapeau contenait des traces de mercure.En haut : E. Baumann et Sohne Hutmacher, Suisse. Droits d’auteur © 2015 Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto (Photo : Ron Wood).

Fig.6 À gauche: Chapeau tricorne contenant du mercure, milieu du 18ème siècle, © Museum de Londres.

À droite: Chapeau melon des années 1910 du Royal Ontario Museum où une analyse a également révélé la présence de mercure.

Christy’s, Londres, 974.117.7, avec la permission du Royal Ontario Museum © ROM.Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

Dans Adorned in Dreams, Elizabeth Wilson souligne les différences entre les classes sociales relatées par Friedrich Engels, en Angleterre, dans son texte The Condition of the Working Class (1844) : « C’est un fait curieux que la production de ces articles, qui servent à la parure personnelle des dames de la bourgeoisie, a les conséquences les plus tristes pour la santé des travailleurs ». Engels avait raison de critiquer les torts causés à la santé des travailleurs lors de la fabrication d’articles de mode pour femmes, mais il restait aveugle aux toxiques contenus dans le couvre-chef qu’il portait lui-même. Aujourd’hui, peu d’hommes portent des chapeaux en feutre de fourrure mais il aurait été socialement inacceptable pour Engels à son époque de quitter la maison sans son couvre-chef. Aujourd’hui, le port du chapeau n’est pas obligatoire, mais le chapeau a toujours été un vêtement essentiel dans de nombreuses cultures. Avant le chauffage central, les chapeaux étaient importants pour des raisons pratiques : ils aidaient à garder la tête de leurs propriétaires au chaud et au sec. Des coutumes sociales élaborées pour mettre, enlever et porter les chapeaux, désuètes pour notre société contemporaine, étaient des rituels courants renforçant les hiérarchies de classes. Les chapeaux, ainsi que les chaussures, constituaient un des éléments onéreux mais essentiels de la garde-robe d’un homme.

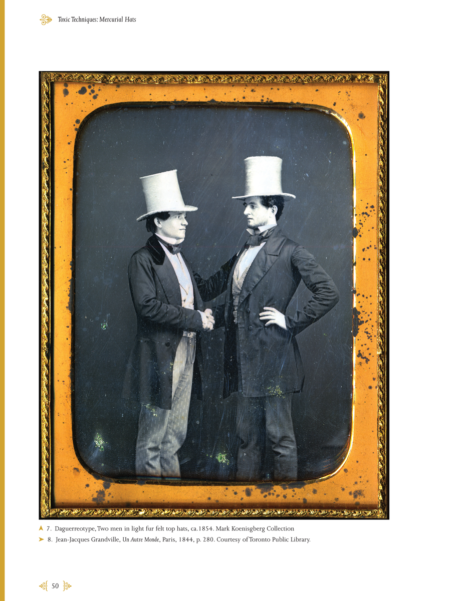

Une photographie au daguerréotype représente ce qu’était le costume bourgeois de l’époque victorienne : élégantes redingotes noires, impeccables plastrons de chemise blancs, gilets, cravates et pantalons bien coupés (Fig. 7). Les modèles y portent deux chapeaux légers qui révèlent une texture velue sur le bord et la couronne. Les hommes se serrent la main pour montrer leur amitié ou peut-être une attitude fraternelle, un homme plaçant sa main sur l’épaule de l’autre homme. Cette image illustre l’importance prises par ces nouvelles industries et technologies conçues pour mettre en lumière le caractère brillant de l’homme moderne. Parallèlement au boom de l’édition des magazines de mode pour hommes avec des titres comme Le Narcisse, figure mythique qui est tombée amoureuse de sa propre image, il est devenu possible de voir nettement son propre reflet de pied en cap dans un miroir psyché ou de voir son portrait photographique. Le daguerréotype, technique photographique inventée en 1839, était une image nette et unique sur une plaque d’argent hautement polie et semblable à un miroir. Les vapeurs de mercure ont également été utilisées au cours de leur fabrication, ce qui signifie qu’à la fois les chapeaux et leurs images « exposaient » les hommes aux toxiques[12].

Fig.7 Daguerréotype : deux hommes portant des chapeaux haut-de-forme clairs en feutre de fourrure,

vers 1854. Collection Mark KoenisgbergPage du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

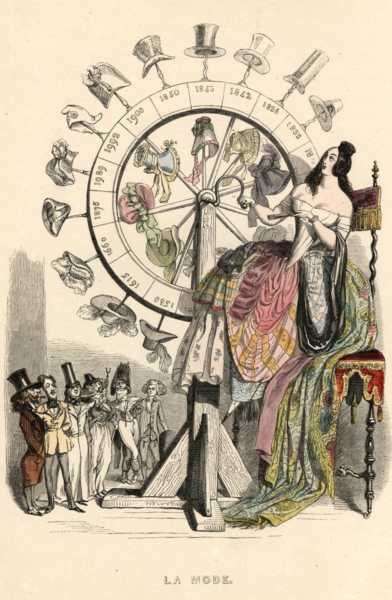

Malgré leur fonctionnalité indéniable, nous arguerons que la forte valeur d’échange des chapeaux en feutre de fourrure dans le commerce de la mode les rendait aussi « irrationnels » et désirables que les vêtements pour femmes. Nous utilisons intentionnellement le mot « irrationnel », car l’histoire de la tenue vestimentaire des hommes est souvent mise en scène comme une trajectoire rationnelle et linéaire. Pourtant, pendant plus de 200 ans, les médecins ont accumulé des preuves sur une industrie chapelière qui fabriquait un objet protégeant la tête, siège de la raison, mais qui causait des dommages neurologiques aux chapeliers « fous », qui les fabriquaient. En 1844, le caricaturiste parisien Jean-Jacques Grandville fit une satire sur la tyrannie de « La mode » (Fig. 8). Grandville accusait les tailleurs et les couturiers d’être des « bourreaux » diaboliques de la tyrannique Queen of Fashion, représentée en géante qui tournait une manivelle.

Ce n’est pas la roue de la fortune, mais un instrument de torture appelé roue de rupture ou roue de Catherine. Il était employé pour écarteler les criminels les plus odieux et leur casser les membres, provoquant une mort lente et douloureuse. Malgré les accusations de Grandville, les fabricants de vêtements n’étaient ni des agents malfaisants ni des bourreaux. La situation était à l’opposé. Leur commerce leur a nui : les tailleurs avaient notoirement le dos courbé à force de se pencher toute la journée sur leur travail, tandis que les couturières mal payées étaient souvent obligées de se tourner vers la prostitution pour subvenir à leurs besoins. Bien qu’Engels ait accusé les consommatrices bourgeoises, les hommes et leurs chapeaux en renouvellement permanent portaient une grande part de responsabilité dans la production de « tristes conséquences » pour le corps des chapeliers, notamment invalidité et mort prématurée.

Fig.8 Jean-Jacques Grandville, Un Autre Monde, Paris, 1844, p. 280. Avec la permission de Toronto Public Library [Bibliothèque publique de Toronto].

Tours de chapeau

Tirer un lapin d’un chapeau est un acte de prestidigitation symbolisant la magie elle-même. Les origines du tour de chapeau suggèrent qu’il a été inventé au début du XIXème siècle, peut-être en 1814 par le magicien parisien Louis Comte[13]. Dans les années 1830, John Anderson fit apparaître une « ménagerie » entière de lapins sous les chapeaux des spectateurs[14]. Ainsi, ce tour de magie fut appelé le « vieux chapeau », sans doute un jeu de mots sur la fourrure de lapin utilisée dans la fabrication du chapeau. Dans une boucle humoristique, le lapin est tué pour devenir un chapeau et le magicien « le réanime » en un lapin vivant. Bien que les lapins aient subi un processus complexe lors de leur transformation d’animal vivant en couvre-chef, les chapeaux conservent souvent leur texture veloutée, douce, quasi animalière (« nap »), dans la texture du poil sur le chapeau ; le produit fini nécessitait de fréquents toilettages et brossages, appelés « pelotage et bichonnage », afin de façonner le bord, le rehausser et maintenir le lustre brillant de la fourrure[15]. Ces termes décrivent également le fait de caresser et choyer un petit animal de compagnie, et dans un cadre domestique, ce que font les épouses attentionnées qui brossent les chapeaux de leurs maris. Dans l’histoire de Sherlock Holmes de 1892, « L’aventure de l’escarboucle bleue », un agent de police donne au détective un indice potentiel : un chapeau « très miteux et peu recommandable ». En se basant sur une observation détaillée, Holmes déduit que son propriétaire « est un homme qui mène une vie sédentaire, sort peu, est totalement hors de condition physique, est d’âge moyen, a les cheveux grisonnants qu’il a coupés ces derniers jours ». Il suppose que sa femme « a cessé de l’aimer », se basant pour cette dernière observation, sur la poussière de maison, brune, se trouvant sur le chapeau qui « n’a pas été brossée depuis des semaines ». Il dit à son célèbre compagnon : « Quand je te vois, mon cher Watson, avec une accumulation de poussière sur ton chapeau pendant une semaine et quand ton épouse te permet de sortir dans un tel état, je crains que tu n’aies eu le malheur de perdre l’affection de ta femme[16] ».

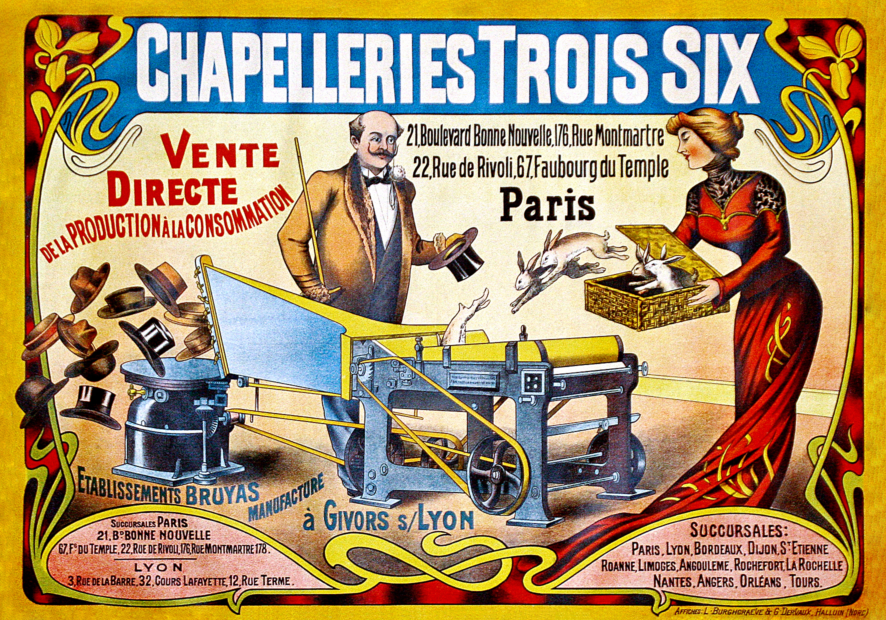

Alors que le brillant travail de détective d’Holmes évoque « par magie » l’histoire d’un propriétaire absent, une publicité Art Nouveau pour les chapeaux Bruyas, joue sur l’acte classique du magicien en inversant le tour du chapeau (Fig.9). Une femme à la mode, qui ressemble étrangement à l’assistante d’un magicien en robe rouge, ouvre un petit panier en osier. Cinq lapins, exactement le nombre nécessaire en moyenne pour fabriquer un chapeau, sautent dans la trémie d’une machine à « basoner » ou « bâstisseuse ».

Cette machine, qui devint en 1855 la première machine industrielle à être utilisée dans la confection de chapeaux, soufflait la fourrure sur un grand cône[17]. Sur cette affiche, le cône a été remplacé par onze chapeaux finis dans une variété de formes et de matériaux, allant du fedora au canotier. Un gentilhomme, qui ressemble à un magicien, se tient entre le lapin et le produit étincelant final, ôtant poliment son chapeau devant l’assistante. Cette image date de 1900 environ, la période exacte où le processus entier de fabrication du chapeau pouvait enfin être « magiquement » accompli par des machines[18].

Cette publicité séduisante élude complètement la transformation mortelle pour les lapins et le travail qui a empoisonné les chapeliers. Un rapport commandé par les syndicats de travailleurs suggère qu’au moment où cette affiche publicitaire a été imprimée, les ouvrières qui utilisaient des bâtisseuses souffraient en fait d’un grave empoisonnement au mercure[19].

Fig.9 Affiche chromolithographique montrant une machine qui transforme les lapins en chapeaux. Établissements Bruyas, vers 1900. Musée du Chapeau, Chazelles-sur-Lyon.

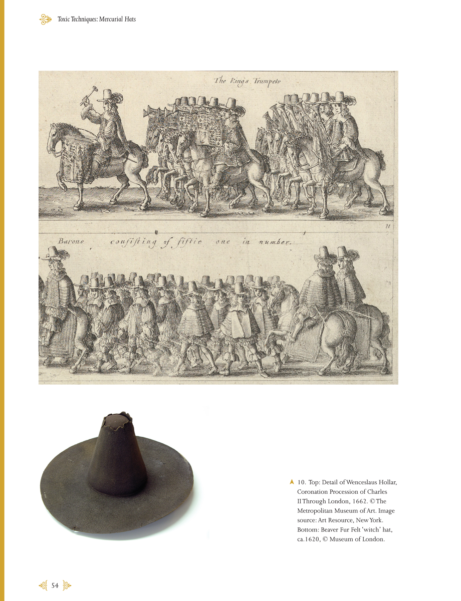

Mais les chapeliers n’ont pas toujours été empoisonnés. Historiquement, les chapeaux en fourrure de castor, ou « Bevers », étaient les chapeaux les plus chers. Contrairement au feutre de laine qui était lourd et qui perdait sa forme lorsqu’il était mouillé, les poils de castor étaient souples, légers, imperméables, résistants et chauds[20]. La fourrure de castor était si prisée que l’espèce animale s’est éteinte en Europe au XVIème siècle. Les entrepreneurs se sont tournés vers de nouvelles sources de fourrure en Amérique du Nord. Atteignant son apogée au XVIIème siècle, les modèles de formes raides et à larges bords étaient les favoris des cavaliers fringants et des puritains plus sobres. Les victoires militaires suédoises pendant la guerre de Trente ans (1618-1648) ont donné naissance à de nouveaux styles de couvre-chefs comme le « clocher à larges bords » ou le chapeau « en pain de sucre » à la mode pour les hommes et les femmes[21]. Daté des années 1620, un exemple rare de ce que nous pourrions appeler un chapeau de « sorcière » a perdu son sommet, car le matériau s’est craquelé lorsqu’il a séché (Fig.10). La fourrure est épaisse par rapport aux exemples modernes, mais lorsqu’on soulève le chapeau, elle paraît étonnamment légère pour sa taille.

Fig.10 En haut : Détail de Wenceslaus Hollar, Coronation Procession of Charles II Through London [Procession pour le couronnement de Charles II à Londres],

1662. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source de l’image : Art Resource, New York.En bas : chapeau de ‘sorcière’ en fourrure de castor, vers 1620, © Museum de Londres.Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

La fourrure de castor pur n’a pas besoin de mercure. Les poils de castor ont une structure en barbelée, et la meilleure qualité de fourrure était obtenue en vieillissant préalablement la peau et en modifiant son caractère chimique par contact direct avec le corps humain. Comme l’a écrit un premier colon néerlandais : « à moins que la fourrure de castor soit sale et grasse, elle ne feutrera pas ».

On obtient la meilleure qualité de cette fourrure en la portant directement sur la peau car elle vieillit et se modifie chimiquement à ce contact. Ainsi, une peau de castor déjà « usée » ou « enduite » ayant servi de doublure pour des manteaux en Russie ou ayant été portée par des autochtones en Amérique, « sur le corps nu pendant un bon moment », et salie par la sueur et la graisse, se travaille bien et donne de « bons chapeaux ».. Une partie de « castor gras » pouvait être mélangée à cinq parties de « castor sec » pour créer des chapeaux haut de gamme.

La gravure de Wenceslaus Hollar représentant la procession du couronnement du roi britannique Charles II, montre l’élite sociale et politique vêtue de chapeaux de castor à haute couronne décorés de plumes. Le célèbre journaliste anglais Samuel Pepys a acheté un coûteux chapeau de castor en 1661, et ne le portait que pour des événements sociaux majeurs comme la fête du maire[22]. Quand il partait simplement à cheval, il portait un autre chapeau pour « sauver son bever[23] ».

Les écrits de Pepys montrent à quel point il appréciait son chapeau de castor. Cependant, au XVIIIème siècle, les approvisionnements en castor se sont taris d’une part à cause d’une chasse excessive et d’autre part du fait de la guerre qui a interrompu la chaîne d’approvisionnement. C’est alors que l’on commença à remplacer la fourrure de castor par celle du lapin et de lièvre bon marché et disponible localement. Cependant restait un problème : ces fourrures n’étaient pas facilement transformées en feutre. Pour affaiblir chimiquement la kératine autour des poils, les chapeliers devaient utiliser une solution, appelée « secret », et dont la composition chimique exacte était un secret commercial. On l’appelait aussi eau-forte ou liqueur du chapelier. Le secret reproduisait les effets chimiques de la transpiration humaine sur le processus de feutrage et remplaçait le processus biologique naturel lent consistant à porter la fourrure sur la peau par une technologie plus rapide, plus efficace mais biotoxique.

« Luxe homicide »

John F. Crean, historien de l’économie, issu d’une famille canadienne de fabricants de chapeaux du XXème siècle, ne mentionne que brièvement les effets, sur la santé, de l’intoxication au mercure dans son article fascinant sur l’économie du commerce de la fourrure. Il souligne l’avènement de la solution au mercure comme une innovation technologique analogue à l’invention du procédé Bessemer de raffinage de l’acier, breveté en 1855[24], qui a rendu la technologie de l’acier abordable et a remplacé le fer forgé par un acier résistant à la rouille, pour l’architecture et l’industrie.

La fabrication du chapeau au XVIIIème siècle était encore artisanale et non une industrie lourde comme la production d’acier ou de textiles. Cependant, à l’instar des autres métiers du luxe, elle faisait partie de ce que l’historien économiste Jan de Vries appelait la « révolution industrieuse », qui a précédé la révolution industrielle[25]. Dans le cadre de cette révolution, de nouvelles techniques utilisant le mercure ont été introduites pour feutrer des fourrures pour des sommes modiques et pour accélérer le processus de fabrication de chapeaux, mais dans un certain nombre d’usines, les nouvelles procédures de production « provoquèrent l’apparition de nouvelles conditions sanitaires[26] ». Dès 1778, l’un des premiers démographes français notait que ces nouveaux luxes étaient en train de tuer les classes ouvrières. Jean-Baptiste Moheau réclamait une taxe sur le « luxe homicide » et écrivait :« il n’est presque point de monument qui ne soit pas cimenté par du sang, presque point de vêtement qui n’en soit teint ; et le résultat des efforts qu’on a fait pour perfectionner les Arts mécaniques, a été, relativement à la population, de créer une multitude de poisons inconnus aux siècles précédents[27] ». La fabrication de chapeaux était l’archétype des empoisonnements occasionnés. Malgré la perspective positive de Crean sur le processus de secrétage (carroting process : traitement chimique de feutrage), ses effets néfastes ont fait de ce commerce un champ de bataille entre travailleurs et propriétaires d’ateliers au cours du XVIIIème siècle, une bataille que les ouvriers chapeliers ont finalement perdue face aux intérêts économiques des fabricants[28].

Deux légendes différentes expliquent comment les chapeliers ont découvert les propriétés de feutrage du mercure. Les deux reposent sur l’utilisation médicale courante du mercure. Les ouvriers utilisaient l’urine pour compléter le liquide acide dans les cuves utilisées pour faire bouillir et feutrer la fourrure. Dans un atelier, un chapelier aurait produit un feutre de meilleure qualité que ses collègues. Sa syphilis était traitée avec un composé du mercure inséré dans son pénis. Cette urine contenant du mercure aidait miraculeusement à feutrer ses chapeaux[29]. Dans une seconde histoire britannique, un médecin utilisait le mercure imprégné sur une peau de lapin pour cicatriser le cancer du sein d’une femme. Cette peau de lapin avait été utilisée par un chapelier, et fut tracée jusqu’à ses origines[30]. La date exacte de son introduction est inconnue, mais les artisans avaient probablement compris les propriétés de feutrage du mercure au XVIIème siècle. Toutefois il a été interdit en 1716 par les statuts professionnels des artisans sur la qualité du produit fini, et peut‑être pour protéger la santé des travailleurs[31]. Cette interdiction ne devait pas durer longtemps. Les huguenots, dont beaucoup étaient chapeliers, avaient apporté leur « secret » en Angleterre quand ils se sont enfuis. Divers récits racontent qu’un chapelier français l’a réimporté à Paris un peu plus d’une décennie plus tard[32].

Dans les années 1730, le secrétage est au cœur d’une bataille juridique opposant la corporation des chapeliers marseillais à François Carbonnel, propriétaire d’un atelier qui avait commencé à utiliser du mercure en 1732. Au tribunal, Carbonnel utilise des arguments économiques à l’appui de sa demande. Le mercure lui permettait d’utiliser des matériaux moins coûteux, rendant ses produits compétitifs sur le marché par rapport aux chapeaux britanniques plus légers qui étaient alors recherchés par les consommateurs dans des climats plus chauds comme l’Espagne et l’Italie[33]. La corporation des chapeliers soutenait que les chapeaux fabriqués avec du mercure étaient de mauvaise qualité et tombaient en morceaux, et que Carbonnel introduisait une concurrence déloyale au sein de la corporation. Elle se plaignait également des effets nocifs du mercure sur la santé, une accusation niée par Carbonnel[34].

Le tribunal a statué contre lui et le mercure a de nouveau été interdit à Marseille, puis Lyon et Paris, et dans d’autres grands centres de fabrication de chapeaux en France. En dehors des zones urbaines, cependant, les chapeliers fabricants ont commencé à utiliser du mercure. La politique et l’économie ont finalement conduit à son adoption générale. Dès la première moitié du XVIIIème siècle, les peaux et les fourrures de castor étaient devenues de dix à cinquante fois plus chères que celles de lapins et de lièvres[35]. Le castor exigeait également des compétences considérables. Il fallait six à sept heures pour transformer la fourrure de castor brute en un chapeau de feutre tandis que trois heures suffisaient pour le lièvre ou le lapin. En 1782, un chapeau d’homme, « ordinaire », pouvait se vendre entre 3 et 6 livres, tandis que le chapeau de castor coûtait quatre fois plus cher[36]. Pour cette raison, l’emploi du mercure, interdit en 1735, fut à nouveau légalisé à Marseille en 1751[37].

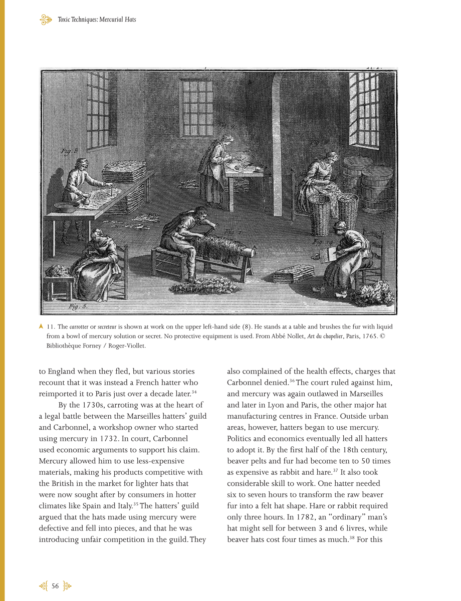

Fig.11 Le secréteur ou carrotter au travail apparaît en haut à gauche (8). Il est debout à une table et brosse la fourrure avec un liquide provenant d’un bol de solution mercurielle, ou secret.

Il n’utilise aucun équipement protecteur. In : Abbé Nollet, Art du chapelier, Paris, 1765. © Bibliothèque Forney / Roger-Viollet.Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

Lorsqu’en 1763 la France perdit au profit des Britanniques le Canada et ses peaux de castor, l’utilisation du mercure se répandit encore davantage, « les chapelleries privées de castor sont devenues plus meurtrières. Le gouvernement anglais, bien que ce soit une chose pénible à dire, ne continue pas moins de tuer nos ouvriers, en temps de paix ou de conflit ». Lorsqu’en 1763 la France perdit au profit des Britanniques le Canada et ses peaux de castor, l’utilisation du mercure se répandit encore davantage. Le secrétage n’était que l’une des nombreuses opérations mettant en péril les chapeliers. Un manuel de fabrication des chapeaux publié par l’abbé Nollet en 1765, expliquait la technique de brossage utilisée par les travailleurs[39] (Fig. 11). Après avoir été coiffés, les poils du pelage étaient retirés de la peau par « arçonnage » avec un long arc ou un arçon, et le mercure présent sur la fourrure diffusait dans l’espace clos et sans air. Les fenêtres des ateliers étaient fermées même par temps chaud pour empêcher que les courants d’air ne dispersent les poils fins. Différents problèmes de santé apparaissaient à l’étape suivante, lorsque les fouleurs façonnaient le feutre à l’aide d’un rouleau en bois ou de leurs mains. Par la combinaison de la chaleur, de l’humidité, des produits chimiques et des frictions, ils réduisaient la taille de la « cloche » de feutre de moitié en la plongeant pendant plusieurs heures dans de l’eau bouillante et acide. Une peinture de Jean-Antoine Berger datant de 1904 illustre ce processus brûlant, épuisant, mais requérant beaucoup d’habileté (Fig. 12). On y voit cinq chapeliers qui travaillent autour d’une table à fouler traditionnelle en bois, ses côtés étant inclinés vers une cuve en métal située au milieu. Le feutre est travaillé par quatre « fouleurs » grisonnants, dont deux sont nus jusqu’à la taille pour se rafraîchir le corps. Le cinquième homme, torse nu, chargé de maintenir un feu de bois sous la bouilloire et de faire l’appoint en vitriol et en eau chaude, boit du vin directement à la bouteille. Un journal professionnel de 1862 suggère que, même si le travail de foulage est épuisant, fait transpirer et que le travailleur doive boire fréquemment pour étancher sa soif, « malheureusement, ce sont presque toujours les boissons alcoolisées qu’il préfère[40] ». Il suggère aussi de faire bouillir un litre de café sucré avec de l’extrait de réglisse comme alternative bon marché et plus saine.

Fig.12 Jean-Antoine Berger, La planche ou Chapeliers fouleurs, 1904. Musée du Chapeau, Chazelles-sur-Lyon.

Comme les « feutriers », les « fouleurs » portent des tabliers, mais pas de gants de protection ni de masques. Le foulage corrode les mains du fouleur et les rend calleuses. Elles absorbent alors des quantités encore plus grandes de mercure par les fissures de la peau. À chaque respiration, les ouvriers inhalent la vapeur mortelle émanant de la cuve. Les effets du poison sont renforcés par l’alcool, qui peut empêcher le foie de l’éliminer efficacement[41]. Le mercure est également libéré dans l’environnement local.

Dès l’introduction du mercure dans les pratiques, les médecins ont constaté ses effets néfastes. Jacques-René Tenon a été le premier à signaler un empoisonnement chronique au mercure chez les professionnels du chapeau. En 1757, ce médecin français de 33 ans, qui vient d’être nommé à la chaire de pathologie du Collège français de chirurgie, a personnellement visité les six principaux ateliers de chapellerie de Paris. Bien que certains d’entre eux lui aient semblé avoir des ouvriers légèrement plus sains que d’autres, ses observations sont accablantes : dans l’atelier de M. Carpentier, il fait remarquer qu’aucun ouvrier n’atteint la cinquantaine, que les mains de la plupart d’entre eux tremblent dès le matin, et qu’ils « étoient sujets à des sueurs abondantes et à une expectoration de matière visqueuse ». Ils sont tous squelettiques « maigres, faibles et réduits à boire des spiritueux pour se soutenir et satisfaire au travail de la journée ». Il remarque que tous « faisaient beaucoup d’enfants, en élevaient peu ; la plupart périssaient avant la quatrième année[42] ». Dans un autre atelier, le propriétaire de l’usine, lui-même, est mort à 54 ans. Les chapeliers de l’atelier Letellier, qui, jusqu’à récemment, utilisaient des fourrures de haute qualité prélevées sur des castors chassés en hiver, alors qu’elles étaient plus épaisses, se sentaient mieux, ils les avaient fait bouillir dans de l’eau non traitée et ils présentaient beaucoup moins de symptômes que les autres[43]. La solution de mercure qui avait été introduite chez Letellier seulement quelques années auparavant était beaucoup plus diluée que celle utilisée dans les autres ateliers. Tenon en a conclu que l’opération de « secrétage » était en cause dans les problèmes sévères de santé et les décès prématurés. Il s’est également entretenu avec Beaumé, un chimiste et pharmacien qui vendait la plupart des articles de feutrage pour chapeaux. Celui-ci l’a informé que les commandes allaient de 1 à 3 livres de mercure pour 16 livres d’acide nitrique. Tenon en a déduit que les chapeliers ne savaient pas encore quelles proportions de mercure étaient suffisantes pour être efficaces et préserver en même temps la santé des travailleurs. Il appelle alors les propriétaires d’usines à réduire l’usage du secrétage ou, mieux encore, à substituer l’utilisation du mercure par « un procédé utile à l’art sans qu’il soit aussi préjudiciable aux artisans[44] ».

Les écrits de Tenon furent inédits et ses avertissements sont restés lettre morte. Les médecins ont continué à rapporter les signes cliniques de la maladie des chapeliers, qui souffraient de convulsions, de tremblements des membres et de paralysie. Achard, qui a mené une enquête de trois ans sur la question, a décrit la mort d’un bébé de cinq mois qui avait inhalé de la vapeur de mercure dans l’atelier et la maison de ses parents[45]. En 1776, la Gazette de santé qualifiait l’utilisation du mercure d’ « inutile, bizarre et abusive[46] ». Dans « Les arts et les sciences en France et en Grande-Bretagne » des concours ont été lancés pour la recherche d’un procédé chimique alternatif. Ces mesures ont eu peu d’impact réel[47]. En fait, après la Révolution française et sous l’empire napoléonien, la situation s’est aggravée, la guerre ayant pris le pas sur les préoccupations sanitaires. Les travailleurs n’avaient pas le droit à la parole[48]. Quelques mesures ont été prises pour améliorer les équipements de protection. Un chapelier a même conçu des masques et des éponges pour ses collègues, mais dans l’ensemble, la situation a empiré au début du XIXème siècle, atteignant un sommet dans les années 1820[49]. Il est habituel de concevoir Paris comme la capitale de l’art, de la culture et de la mode, mais des historiens français spécialistes de la pollution de l’environnement, tels qu’André Guillerme et Thomas Le Roux, soutiennent qu’entre 1780 et 1830, Paris était devenue une capitale « industrielle », fabriquant à la fois des produits de luxe et une large gamme de produits chimiques utilisés dans ses manufactures[50]. Ils ont réévalué le rôle joué par le mercure dans les industries parisiennes, et accordé une attention particulière à la contamination par les métaux lourds et à la pollution généralisée qu’ils provoquent.

Comme le fait valoir Paul Blanc, les dommages ne se limitent pas à l’organisme des travailleurs, car « il n’y a pas de frontière absolue entre les risques professionnels et environnementaux[51] ». Des études géochimiques récentes prouvent qu’à partir des années 1820, les niveaux de mercure dans le sol de Danbury et Norwalk, centres historiques de commerce de chapeaux dans le Connecticut en Amérique, étaient de trois à sept fois plus élevés que les niveaux antérieurs à la période industrielle[52]. Le mercure s’y concentre toujours près des anciennes fabriques de chapeaux. Des inondations et des phénomènes météorologiques extrêmes continuent de le déverser dans le détroit de Long Island plus de 150 ans après son dépôt[53]. À Paris, les cuves des « fouloirs » bouillonnaient et volatilisaient les sels de mercure sous la forme la plus biotoxique du métal[54]. Ces sels s’oxydaient et atterrissaient dans les rues et sur les toits où ils contaminaient les réserves de nourriture et la nappe phréatique[55]. À l’apogée de la popularité du chapeau de feutre à Paris dans les années 1820, il y avait deux à trois mille chapelleries concentrées dans une zone densément peuplée du centre de Paris, sur la Rive Droite de la Seine.

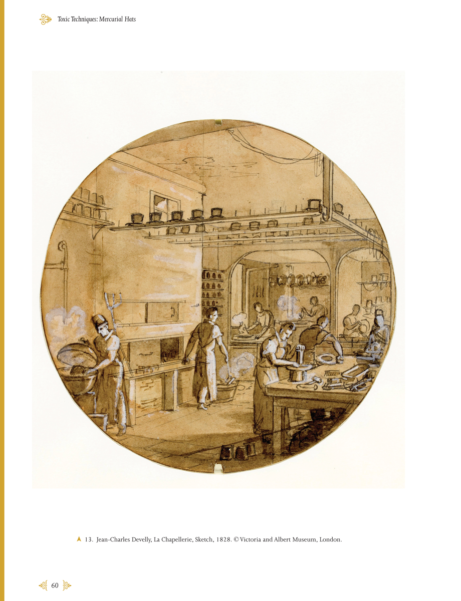

Bien que le mercure ait été reconnu comme une substance dangereuse, la Préfecture de police ne l’a pas jugé suffisamment préjudiciable pour maintenir les ateliers éloignés des zones résidentielles. En 1825, les chapeliers parisiens fabriquaient près de deux millions de chapeaux par an. La quantité annuelle de mercure utilisée s’élevait à dix kilogrammes de mercure par « secréteur » par an. Si on regroupe toutes les industries employant le mercure dont les doreurs, les fabricants de miroirs et les chapeliers, on constate qu’elles libèrent près de six cents tonnes de mercure sur la Rive Droite de Paris entre 1770 et 1830[56]. Les nuages noirs de vapeur de mercure qui flottaient constamment dans les ateliers des chapeliers et dans les rues devaient être un spectacle horrifiant. Selon des récits de témoins oculaires, cela dérangeait les gens et effrayait les chevaux[57]. Pendant l’hiver 1828 et en mai 1829, à l’apogée de la consommation de mercure à Paris, il y eut une épidémie massive d’acrodynie ou maladie de Pink, nommée ainsi à cause des éruptions cutanées roses, qui ont touché plus de 40 000 habitants. Alors que certains ont attribué cette épidémie à l’arsenic ou au plomb, l’historien André Guillerme affirme que c’est le mercure provenant des industries locales qui a empoisonné des dizaines de milliers de Parisiens. Ironiquement, l’été précédant cet empoisonnement massif, le peintre Jean-Charles Develly, en visite dans des ateliers de chapeliers parisiens conçoit un dessin d’assiette pour la manufacture de porcelaine de Sèvres (Fig. 13)[58]. Le service de vaisselle de 180 pièces uniques, peintes à la main, célèbre les arts industriels. Les pièces comprennent au centre, des cartouches représentant des ateliers de fabrication de cent cinquante-six produits différents, allant de la, si utile, boîte en carton aux objets de luxe comme les tapisseries des Gobelins et les bijoux en or. Ce service a été probablement commandé par Alexandre Brogniart, chimiste qui dirigeait l’usine de Sèvres et membre du jury de l’Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie Française. Il s’agissait d’une série d’expositions présentant les dernières innovations technologiques et esthétiques des années 1820 en France. Il ne fait pas apparaître les opérations les plus salissantes et les moins recommandables et met en vedette les gestes finaux de transformation des chapeaux en objets de désir du consommateur. Ces gestes incluent la teinture, le blocage et le ponçage ou le picotage du chapeau. On y voit, au premier plan à droite, un ouvrier devant une table qui termine le bord d’un chapeau renversé avec un fer à repasser spécial, de sorte que sous le pinceau de l’artiste, il a l’apparence distinguée et avenante de celui qui repasse les vêtements avec un fer chaud[59]. La dernière assiette sur la chapellerie, en porcelaine dorée, ne subsiste pas, mais le roi Louis‑Philippe avait offert l’intégralité du service au chancelier d’Autriche, le prince Metternich, en 1836[60]. Vraisemblablement, les membres de la cour du prince ont dégusté un délicieux dîner dans l’image d’une des industries françaises les plus toxiques de cette période.

Fig.13 Jean-Charles Develly, La Chapellerie, Croquis, 1828. © Victoria and Albert Museum, Londres.

Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

De la même façon que la création de ces assiettes en porcelaine à la décoration luxueuse a littéralement « doré » les problèmes de l’industrie, des données scientifiques vont être utilisées pour semer le doute sur l’existence des maladies professionnelles. Ce sera le fait, un an après la production de la porcelaine de Develly, soit en 1829, d’une nouvelle génération de professionnels de Santé publique, « les hygiénistes ». Il s’agissait sans doute de chimistes liés à l’industrie voire des industriels reconnus. Ils favorisaient les intérêts économiques de l’industrie au détriment de la santé des travailleurs qu’ils étaient censés protéger [61]. En conséquence, les dommages causés à l’organisme du travailleur furent délibérément occultés et des études de cas personnalisés observés de façon poignante, comme celle de Tenon, ont été revues sous l’angle de la nouvelle « science » abstraite des statistiques. Enfin, les chapeliers eux-mêmes n’étaient pas suffisamment informés des risques de leur travail. En 1829, un manuel britannique visant à aider les jeunes chapeliers à apprendre le métier ne mentionne même pas le mercure en tant qu’ingrédient dans le liquide de secrétage qu’ils utilisaient[62].

Pourtant, les rapports sur ce sujet suggèrent que les chapeliers recherchaient des alternatives au feutre. Beaucoup de collections de musée présentent des chapeaux de forme semblable en versions fourrure et soie. Le haut-de-forme en soie, qui semble avoir été commercialisé dans les années 1790 et vendu par la firme londonienne George Dunnage comme une « imitation de castor[63] » aurait pu s’affirmer comme substitut moins toxique au chapeau en feutre de fourrure. Dans les années 1850, la soie remplace la fourrure et les vrais chapeaux de fourrure de castor deviennent désuets. En 1885, le Cornhill Magazine observe qu’il pourrait y avoir « quelques difficultés à mettre en lumière le castor de nos jours, sauf dans un musée[64] ». Pourtant, le feutre de fourrure toxique continue à être utilisé pour des styles de chapeaux arrondis, modernes, plus informels comme les chapeaux melons, les homburgs et les fedoras et l’empoisonnement se poursuit sans relâche.

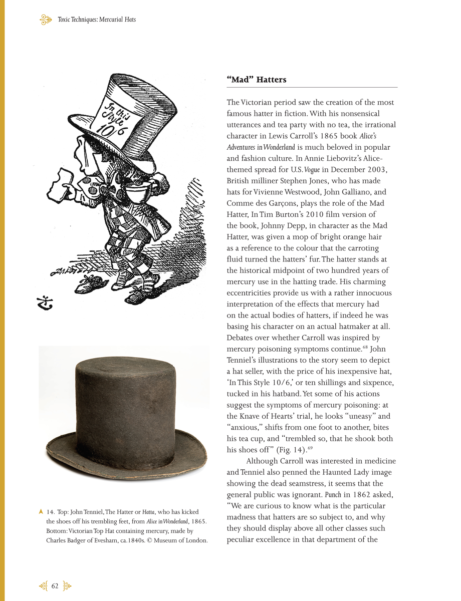

« Mad » Hatters « Les Chapeliers fous »

La période victorienne voit la création du plus célèbre chapelier de la fiction. Avec ses propos absurdes et son thé sans thé, le caractère irrationnel des aventures d’Alice au pays des merveilles (1865) de Lewis Carroll est très apprécié dans la culture populaire et la mode. Dans la série de photos de mode sur le thème d’Alice par Annie Liebovitz pour « US Vogue » en décembre 2003, le modiste britannique Stephen Jones, qui a confectionné des chapeaux pour les maisons Vivienne Westwood, John Galliano et Rei Kawakubo pour « Comme des garçons » joue le rôle du Chapelier fou. Dans la version cinématographique de 2010 du cinéaste Tim Burton, Johnny Depp, incarnant le Chapelier Fou, est affublé d’une tignasse de cheveux orange vif, référence à la couleur dans laquelle le liquide « secret » a teint la fourrure. Le personnage fictif du chapelier se situe au centre historique de deux cents ans d’utilisation du mercure dans le commerce de la chapellerie. Ses charmantes excentricités nous offrent une interprétation plutôt anodine des effets produits par le mercure sur les corps bien réels des chapeliers, même si l’auteur a été inspiré par le personnage d’un véritable fabricant de chapeaux. Les débats se poursuivent encore sur le fait de savoir si Carroll a été inspiré par les symptômes d’empoisonnement au mercure[65]. Les illustrations du livre par John Tenniel semblent représenter un vendeur de chapeaux, où l’indication du prix de son chapeau bon marché, « In This Style 10/6 », soit dix shillings et six pence, dissimule certains signes suggérant les symptômes d’un empoisonnement au mercure : lors du procès du « valet des cœurs », le chapelier a l’air « inquiet » et « anxieux », passe d’un pied à l’autre, mord sa tasse de thé et « tremblait tant, qu’il a perdu ses deux chaussures » (Fig. 14)[66].

Fig.14 En haut : John Tenniel, Le Chapelier ou Hatta, qui a enlevé les chaussures de ses pieds tremblants, dans Alice au pays des merveilles, 1865.

En bas : Chapeau haut-de-forme victorien contenant du mercure, fabriqué par Charles Badger of Evesham, vers les années 1840. © Museum de Londres.Page du livre Fashion Victims, publié par Bloomsbury

Bien que Carroll ait été intéressé par la médecine et que Tenniel ait également décrit l’image de la femme hantée montrant sa couturière morte d’épuisement à cause de son travail, il semble que le grand public méconnaissait certains dangers liés au commerce. En 1862, Punch, s’interroge : « Nous sommes curieux de savoir quelle est la folie particulière à laquelle les chapeliers sont tant sujets et pourquoi ils s’affichent tellement au-dessus de toutes les autres classes du domaine des beaux-arts qui trouvent refuge et protection à Bedlam[67] ». Il termine par un jeu de mots (felt/feeling) soit en français (feutre/émotions ou sentiments) qui ne peut être fidèlement rendu : « nous pensons pouvoir nous risquer à observer que la folie d’un chapelier doit être, par la nature de son métier, particulièrement ce qui est dit pour être plus facilement senti (felt/feutre) que décrit. » « Fou comme un chapelier » ou « mad as a hatter » était un terme argotique qui au sens historique voulait dire «fâché» ou « en colère », et non pas « fou » comme « insensé », qui peut être interprété comme corruption de l’expression «fou comme une vipère » (« adder » en anglais : serpent venimeux[68]). Les chapeliers se sont effectivement engagés dans la contestation politique en France et au Royaume‑Uni. Généralement leur propension à commettre des crimes violents, à mourir plus jeunes et à se suicider était supérieure à celle de leurs pairs[69].

Le débat sur le sujet de l’inspiration de Carroll ne sera jamais réglé ; cependant, de nombreux médecins étaient bien conscients de l’intoxication au mercure. Les symptômes étaient déjà décrits depuis un siècle et réapparaissent dans les textes médicaux français, britanniques et américains avec de légères variantes au cours du siècle et demi suivant. Ils n’ont pas enregistré les noms de chapeliers de la classe ouvrière dans leurs articles de journaux, mais de véritables chapeliers ont été empoisonnés, comme John Butler, un chapelier de 40 ans qui est mort du « Delirium Tremens » à Londres en 1840[70].

À la même époque, Charles Badger, qui était le seul chapelier de la petite ville d’Evesham à Worcester, fabriqua un chapeau haute forme légèrement cabossé contenant du mercure. Cela prouve que les produits toxiques étaient utilisés même dans des ateliers ruraux hors des circuits des grands centres de la mode. En 1857, un ouvrier chapelier strasbourgeois de 61 ans, au « caractère sombre et morose » e suicide en buvant sa solution de secrétage. Il meurt après une agonie de 12 heures 30[71]. Son suicide a sans doute été provoqué par des troubles de l’humeur typiques d’un empoisonnement au mercure, dont la tendance suicidaire. Un texte de 1860 rapporte que les chapeliers malades semblaient fatigués, leurs visages étaient pâles et cadavéreux, et beaucoup présentaient une ligne bleue le long de leurs gencives[72]. Une étude de 1875 mentionne que le mercure provoquait des avortements, des naissances prématurées et des enfants mort-nés chez un petit nombre de femmes qui travaillent avec des peaux toxiques comme « coupeuses de poils[73] ». La fourrure recelait d’autres dangers : de nombreux chapeliers mourraient de maladies respiratoires et quelques-uns ont même contracté l’anthrax, une bactérie présente dans les poils et la fourrure des animaux[74]. Avant l’antibiothérapie, le bacille du charbon/l’anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) également appelé « maladie de la laine[75] », avait un taux de mortalité de 50% chez les personnes affectées. Au cours de la Première Guerre mondiale, des soldats anglais et américains, ainsi que des civils, l’ont contractée en employant, pour se raser, des blaireaux infectés. En effet, certains de ces blaireaux étaient fabriqués à partir de crins de cheval asiatique importés et teints pour imiter la fourrure de blaireau plus coûteuse[76]. Une petite coupure lors du rasage avec la lame d’un rasoir droit ou même un rasoir de sécurité pouvait être mortelle. Aujourd’hui, le bacille de l’anthrax est toujours une biotoxine faisant partie de l’arsenal des armes biologiques et redoutée en tant que « menace terroriste ».

De 1850 à 1900, l’industrie se mécanise de plus en plus et le processus de préparation de la fourrure puis de la confection de chapeaux se fait dans deux usines distinctes, le raclage et le foulage[77]. Les travailleurs sont désormais divisés en « coupeurs » et « coupeuses de poils » ou en chapeliers, mais les deux catégories ont continué à souffrir d’empoisonnement au mercure à des degrés divers. Cette période est marquée de la part des instances gouvernementales, par une surveillance plus organisée des questions de santé au travail, mesure n’entraînant pas nécessairement de réforme ou d’amélioration de la santé. Au Royaume-Uni, un acte de 1895 relatif aux usines et aux ateliers a pris en compte parmi les métiers dangereux quatre maladies professionnelles : les intoxications par le plomb, l’arsenic et le phosphore, ainsi que la maladie du charbon. En 1898, Adelaïde Anderson, inspecteur principal des fabriques, remarque que les coupeurs de fourrures de Londres, en majorité des femmes, souffrent d’hydrargyrisme et l’inspecteur en chef, T.M. Legge appelle à une enquête sur cet événement étrange « parce qu’il est généralement admis que l’intoxication par le mercure est une chose du passé[78] ». En conséquence de l’enquête, dès l’année suivante, Legge a ajouté le mercure à la liste des substances dangereuses, bien que seulement quelques travailleurs si malades qu’ils avaient dû arrêter de travailler, aient été inclus dans les statistiques[79].

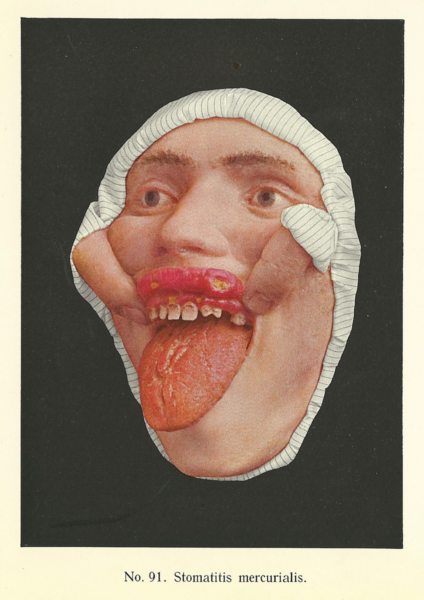

Dans les années 1880, la popularité des modèles de chapeaux plus rigides, comme les chapeaux melon, nécessitant moins de vapeur et de pressage aux fers chauds, auraient apparemment réduit l’ampleur du problème dans le Connecticut[80]. Mais au Royaume-Uni, un rapport de 1902 rédigé par un médecin nommé Charles Porter montre que les taux de mortalité sont toujours élevés. Avec un détachement scientifique qui pouvait sembler froid pour un lecteur ordinaire, Porter note des détails horribles : les dents des travailleurs exposés aux vapeurs de mercure « noircissent et se détachent des gencives en tombant dans un certain ordre, en premier lieu les molaires supérieures et inférieures, puis les canines supérieures et les incisives, et ainsi de suite[81] ». Tandis que Porter utilise ces statistiques effrayantes pour décrire la chute des dents qui affecte les deux tiers des chapeliers, un moulage en cire d’une « Stomatite mercurielle » de la même période dessine une image plus repoussante (Fig. 15). Les vapeurs de mercure endommagent les muqueuses, les gencives, les joues et la langue, qui peuvent tellement gonfler que les patients sont incapables de fermer la bouche[82]. Un praticien de Manchester, Frank Edward Tylecote, l’un des premiers médecins à associer le tabagisme au cancer du poumon dans les années 1920, prend la situation critique des travailleurs au sérieux. Il déclare qu’il peut sentir « l’odeur métallique » des hommes empoisonnés au mercure. Son rapport de 1912, sur « l’empoisonnement industriel » des fabricants de chapeaux note, pour chaque étape de la fabrication, les risques occasionnés à la santé. Il observe que les tremblements mercuriels « empêchent [l’ouvrier] d’effectuer un mouvement plus fin pour lui-même, tels que ceux nécessaires dans le boutonnage de vêtement, le laçage et le délaçage des bottes[83] ». Les souffleurs qui trient mécaniquement la fourrure toxique et les finisseurs, qui polissent les chapeaux avec du papier de verre et inhalent « des quantités considérables de poussières », décèdent souvent des suites d’une maladie respiratoire[84]. Il n’est pas surprenant que les souffleurs aient des problèmes respiratoires. La fourrure devait être soufflée à plusieurs reprises à travers une machine et un inspecteur de santé publique décrit une salle de soufflage dans laquelle il avait « vu voler une fourrure aussi épaisse que la neige lors d’une grosse tempête, et dans une usine, la vapeur et la fourrure avaient formé un feutre solide recouvrant la fenêtre[85] ». Il semble surprenant qu’en 1913, plus de 150 ans après l’étude de Tenon de 1757, les chapeliers utilisent encore 20 kg de mercure pour 100 kg de liquide de secrétage[86].

Fig.15 Moulage en cire montrant les effets de l’empoisonnement mercuriel sur les dents, les lèvres et la langue,

vers 1910, dans Jerome Kingsbury, Portfolio of Dermochromes, vol. II (New

Avec la permission du Gerstein Science Information Centre universitaire de Toronto.Une fin à la folie ?

Avec l’influence croissante de la psychanalyse freudienne, les médecins ont commencé à enregistrer les « perturbations psychiques » causées par un empoisonnement au mercure. Les symptômes en étaient ce que nous appelons maintenant des névroses et des phobies sociales. Cette maladie a été baptisée « éréthisme mercuriel » ; terme dérivé du grec eruthos, ou rouge, à cause de « la rougeur du malade » ou du grec erethidzein, qui met l’accent sur l’irritation. En 1946, les médecins du département de recherche en médecine industrielle du Royaume-Uni notent des symptômes physiques tels que des tremblements mercuriels, puis décrivent avec éloquence l’impact émotionnel de cet « éréthisme » : « L’homme affecté est facilement contrarié et embarrassé, perd toute joie de vivre et craint constamment d’être renvoyé de son travail. Il est intimidable et risque de perdre le contrôle de lui-même devant les visiteurs. Ainsi, à l’usine, si l’on ne s’arrête pas de le regarder, un tel homme jettera parfois ses outils en se mettant en colère contre l’intrus et en disant qu’il ne peut pas travailler s’il est observé[87] ». Même si aucun travailleur d’usine n’apprécie la présence intrusive de médecins sur le lieu de travail, celui qui souffre d’empoisonnement mercuriel peut devenir contrarié et violent

Au début du XXème siècle, es organismes des chapeliers ont été soumis à un examen scientifique de plus en plus sophistiqué, tout comme les chapeaux qu’ils fabriquaient. En 1912, Tylecote demanda à un expert d’effectuer une analyse chimique d’un chapeau. Il contenait une quantité impressionnante de toxique : Une partie pour 800, soit l’équivalent de une once de mercure pour 400 chapeaux pesant deux onces chacun. Dans les années 1920 et 1930, les responsables de santé publique étudient la quantité de mercure évaporée au cours du processus de fabrication de chapeaux ; ces quantités de mercure dans la fourrure et la poussière posaient problème[88]. La situation était compliquée car certains ateliers étaient plus sûrs que d’autres. Une lettre de 1937 du Docteur André Viniezki aux usines Fléchet, situées au centre des chapeliers de Chazelles-sur-Lyon, indique qu’il a traité deux fois Mme Durbize, jeune femme de 29 ans, pour « intoxication au mercure avec tremblement ». Elle avait d’abord été obligée de suspendre son travail pendant deux mois, puis était revenue à l’atelier, était à nouveau tombée malade et avait eu besoin une seconde fois d’un arrêt de quatre mois pour récupérer. La lettre du Dr. Viniezki implorait les propriétaires de l’usine Fléchet d’embaucher cette femme pour qu’elle puisse quitter son premier employeur, car leurs « installations bien étudiées » protégeaient leurs travailleurs[89]. Vers le milieu des années 1940, un article de vulgarisation scientifique proclame de manière optimiste qu’il n’y aura plus de « chapeliers fous ». Cette annonce fait suite à une déclaration selon laquelle des représentants du gouvernement avaient « exhorté » tous les États à interdire l’utilisation du mercure[90]. Un rapport de santé publique américain de 1940 a révélé que 11% des fabricants de chapeaux en feutre de cinq usines du Connecticut souffraient d’un empoisonnement chronique au mercure[91]. Ces recommandations n’ont pas eu force de loi, n’ont pas été écoutées, et le mercure n’a jamais été officiellement interdit en Angleterre où des sources relèvent son utilisation dans l’industrie du chapeau jusqu’en 1966[92]. La fin effective de son emploi a davantage à voir avec le fait que dans le « Youthquake » des années 1960, la mode du « costumes-cravate » respectable et du « chapeaux feutre » était passée.

Le lecteur attentif de cette étude a sans doute noté que les risques potentiels pour les porteurs de chapeaux n’y sont pas mentionnés. Effectivement après que l’on a évoqué les problèmes nés de la fabrication des chapeaux, il faut soulever la question des risques qu’encourraient ceux qui les portaient. Les niveaux élevés de mercure trouvés dans la poussière de fourrure et dans les chapeaux finis rendaient les médecins suspicieux, mais ils hésitaient à les signaler comme un risque direct pour la santé. Ainsi, l’inspecteur en chef des usines écrit une lettre conditionnelle et provisoire avertissant dans son rapport de 1912 : « La possibilité que l’hydrargyrisme affecte le porteur de chapeaux de feutre ne semble pas être tout à fait écartée[93] ». Nous n’avons aucune preuve que les utilisateurs aient été intoxiqués par le mercure de leur couvre-chef. La façon de réaliser des chapeaux atténuait ce problème car les surfaces extérieures étaient souvent traitées avec de la laque pour les imperméabiliser, ce qui les renforçait. Malgré tout, de petites quantités de poussières de mercure pouvaient être libérées lors du brossage, du bichonnage ou du lustrage des chapeaux destinés à maintenir leur éclat. L’intérieur des chapeaux fut également doublé de satin, de soie, lustré et garni d’un bandeau en cuir (Fig. 16). Le bandeau lui-même pouvait provoquer des réactions allergiques. En 1875, le British Medical Journal publie un article sur « L’empoisonnement par un chapeau », d’un jeune cordonnier polonais qui avait porté cette coiffe, ce qui provoqua chez lui une réaction cutanée si grave qu’il souffrit d’une éruption purulente sur le front, que son visage gonfla et ses yeux se fermaient malgré lui. Le chapeau a été remis à un analyste du secteur public qui a identifié un « colorant contenant du poison » dans la doublure[94]. Des hommes ont témoigné de l’irritation que leur causait le port de leurs chapeaux, mais leurs plaintes se limitaient aux sensations de chaleur et de constriction qu’ils ressentaient. En 1829, une thèse de médecine rédigée par Alexandre Précy affirmait que les chapeaux protégeaient le porteur des chocs à la tête et des objets qui tombaient de haut, mais il craignait qu’ils ne causent également des chutes de cheveux, des infections du cuir chevelu et une « surchauffe ». En bloquant la circulation du sang, le chapeau était censé affaiblir la constitution, provoquer des maux de tête et s’avérait même être « un obstacle à l’exercice de nos facultés intellectuelles[95] ». Toujours soucieux d’utiliser les innovations technologiques pour commercialiser de nouveaux produits destinés aux hommes, les fabricants de chapeaux ont réagi à ces plaintes. Plusieurs chapeaux de la collection du Palais Galliera montrent des bouches d’aération habilement dissimulées au-dessus et sur les côtés, et le design incluait une « bande éponge/sueur », en papier ondulé, sur le front qui pouvait être remplacée si nécessaire.

Le mercure a persisté pendant plus de 200 ans dans le commerce des chapeaux, car il n’était pas perçu comme une menace pour les consommateurs de mode masculine. Bien que le mercure ait lentement tué en majorité les travailleurs masculins dans la production même de ce métier, la dynamique de genre et de classe a joué un rôle dans la longévité de son emploi: la mode n’était pas censée victimiser les hommes des classes moyennes ou supérieures, présumés être immunisés contre ses attraits et ses dangers. En conséquence, les débats sur la prise en compte des dangers du mercure se sont déroulés dans une sphère médicale limitée. Avec des exceptions ambiguës comme celle du chapelier fou de Lewis Carroll, l’inquiétude suscitée par les substances toxiques dans le commerce de la chapellerie n’atteignait pas un large public. Les mouvements populaires de réforme de la santé ne se préoccupaient pas du mercure, qui faisait partie seulement de la législation du gouvernement inspectant les « métiers dangereux ». La littérature sur le commerce, destinée aux chapeliers eux-mêmes, ne diffusait pas d’informations sur les risques du mercure pour les travailleurs, risques qui étaient en grande partie laissés dans l’ombre. Les chapeliers dont le métier pouvait les transformer en corps sans dents, abîmés, timides, bégayants, irritables et tremblants, ont été ignorés et rejetés par la société qui s’en moquait comme de ridicules mais inoffensifs excentriques comme le célèbre personnage littéraire de Lewis Carroll.

Nous avons besoin d’équipements scientifiques pour détecter le métal toxique qui causait les traumatismes, l’invalidité et la mort prématurée des chapeliers, ainsi que les dommages causés à l’environnement par la production même des chapeaux et par le lustre attirant de leur surface. La mode nous séduit si souvent avec sa forme versatile et le feutre de fourrure était le matériau transformable et malléable parfait pour les coiffures à la mode. Néanmoins, les emballages en cellophane, frustrants pour la curiosité du chercheur, les gants que celui-ci doit porter pour les observer de plus près, par ainsi que le logo répulsif « tête de mort/os croisés du V & A rappellent que le poison séculaire utilisé par les créateurs d’origine persiste jusque dans leurs propres fibres. La courte durée de vie de ces objets de mode que sont les chapeaux contraste radicalement avec la longévité des toxiques chimiques sciemment utilisés dans leur fabrication.

Fig.15 Doublure de chapeau haut-de-forme, vers 1910. Chapeau fabriqué par Henry Heath Ltd., 105,107,109,

Oxford St. W. Londres. Fabriqué spécialement pour W&D Dineen Co. Ltd., Temperance and Yonge Streets, Toronto.

Don de Kathy Cleaver. Université Ryerson, FRC2014.07.091A (Photo: Ingrid Mida).

[1].↑ McPhee S.J., (1990), Chapitre 44 “Clubbing,” Clinical Methods : The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations, 3ème éd. (Boston : Butterworths), Houston M.C., (2011), “Role of Mercury Toxicity in Hypertension, Cardiovascular Disease, and Stroke”, Journal of Clinical Hypertension 13, no. 8, 621-627.

[2].↑ “Mercure”, Hygiène du Travail Tome 1 (Genève : Bureau International du Travail, 1925), 4.

[3].↑ Mullins W., (2009), Felt (Oxford : Berg,).

[4].↑ Henderson D., (2001 ),The Handmade Felt Hat (Yellow Springs : Wild Goose Press), 15.

[5].↑ Crean J.F., (1962), “Hats and the Fur Trade”, The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 28, n° 3, 380.

[6].↑ C’est le seul métal qui prend une forme liquide à température ambiante, et s’appelait aussi “vif-argent” car il était liquide, argenté et “vif”, ce qui peut vouloir dire rapide mais aussi animé ou vivant. Il réanimait certainement les peaux d’animaux morts et leur donnait une seconde vie sur les têtes masculines (traduction de l’auteure). It is the only metal that is liquid at room temperature and was called quicksilver because it was liquid, silver-colored, and “quick,” which can mean fast but also quick in the sense of animate, alive, or living. It certainly “enlivened” the fur of dead animals and gave it a second life on men’s heads.

[7].↑ Merler E., Boffetta P., and Masala G., (1994) ,“A Cohort Study of Workers Compensated for Mercury Intoxication Following Employment in the Fur Hat Industry”, Journal of Occupational Medicine, 36, 1260-1264.

[8].↑ artin G. et Kite M., (2007), “Potential for Human Exposure to Mercury and Mercury Compounds from Hat Collections”, Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Materials Bulletin, 30, 14.

[9].↑ Martin G., Kite M., (2003), “Conservator Safety: Mercury in Felt Hats” reproduit dans Changing Views of Textile Conservation, eds. Mary Brooks et Dinah Eastop (Los Angeles : Getty Conservation Centre, 2011), 254.

[10].↑ Ibid., 257..

[11].↑ La majorité des chapeaux analysés au Museum of London qui furent fabriqués entre 1800 et 1850 contenaient du mercure, mais ceux fabriqués dans la deuxième moitié du siècle n’en contenaient pas. Le Royal Ontario Museum a trouvé du mercure dans des chapeaux datant des deux premières décennies du XXème siècle. J’exprime toute ma reconnaissance à Marie-Laure Gutton pour m’avoir donné accès à la vaste collection de chapeaux du Palais Galliera à Paris.

[12].↑ Guillerme A., (2007), La naissance de l’industrie à Paris : entre sueurs et vapeurs. 1780-1830 (Seyssel, Champ Vallon), 377. L’image photographique dans les daguerréotypes est développée au moyen d’amalgame de particules d’argent et de mercure, procédé appelé “mercurialisation” à l’époque victorienne. La plaque exposée était tenue au-dessus d’un bain de mercure chauffé à 70‑80 degrés Celsius. L’air dans l’atelier était tellement rempli de mercure que celui-ci recouvrait les chaînes de montre en or. Newhall B., (1976), The Daguerreotype in America (New York : Dover), 125-126.

[13].↑ McDowell C., (1992), Hats : Status, Style, and Glamour (New York : Rizzoli), 74.

[14].↑ Milbourne C., (1973), An Illustrated History of Magic (New York : Thomas Crowell), 113. Un autre spectacle de vaudeville populaire datant de la Renaissance française était appelé chapeau ou chapographie. L’artiste enroulait et façonnait un anneau de feutre pour produire un nombre étonnant de différentes formes, imitant les maniérismes de chaque type et classe de porteurs de chapeaux, masculins et féminins.

[15].↑ Bolomier E., (1996), Le chapeau: grand art et savoir-faire (Paris, Somogy et Musée du Chapeau), 50.

[16].↑ Conan Doyle A., (2009), “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle”, in : The Penguin Complete Sherlock Holmes (London : Penguin), 247.

[17].↑ Bolomier E., (1996), Le chapeau, 17.

[18].↑ Ibid., 18.

[19].↑ Bonneff L., Bonneff M., (1990), Les métiers qui tuent (Paris, Bibliographie Sociale), 46.

[20].↑ Crean J.F., (1962)“Hats and the Fur Trade”, 375.

[21].↑ Henderson D., (2000), The Top Hat: An Illustrated History of Its Manufacture and Styling (Yellow Springs, Mont : Wild Goose Press), 16.

[22].↑ Il paya 4 livres et cinq shillings pour son chapeau de castor. Son chapeau habituel avait coûté seulement 35 shillings. Note de bas de page: vol. 1:197 (27 juin 1661), vol. 1:230 (29 octobre 1661), vol. 1:274 (26 avril 1662). Pepys S., (1910), Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys, ed. Rev. J. Smith, 4 vol. (Boston : C.T. Brainard).

[23].↑Ibid., vol. 1 : 274 (26 avril 1662).

[24].↑ Crean J.F., (1962), “Hats and the Fur Trade,” 380.

[25].↑ De Vries J., (1994), “The Industrial Revolution and the Industrious Revolution” Journal of Economic History, 54, n° 2, 249-270.

[26].↑ Le Roux T., (2010), “Santés ouvrières et développement des arts et manufactures au XVIIIème siècle en France”, dans Economic and Biological Interactions in the Pre-industrial Europe from the 13th to the 18th Centuries, ed. Simonetta Cavaciocchi (Firenze : Firenze University Press), 573‑574.

[27].↑ Moheau J-B., (1998), Recherches et considérations sur la population de la France 1778, Gallica e-source, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 219.

[28].↑Ibid., 221.

[29].↑ Heal C., (2013). “Alcohol, Madness and a Glimmer of Anthrax : Disease among the Felt Hatters in the Nineteenth Century”, Textile History, 44, n°1, 105.

[30].↑Crean J.F., (1962), “Hats and the Fur Trade”, 380.

[31].↑Le Roux T., (2010), “Santés ouvrières”, 574.

[32].↑Ce chapelier était nommé soit Dubois en 1727, ou Mathieu en 1735. Ibid.

[33].↑En Angleterre il était légal d’utiliser le mercure. L’utilisation du mercure n’a, en fait, JAMAIS fait l’objet d’une interdiction légale en Grande-Bretagne.

[34].↑Le Roux T., (2010), “Santés ouvrières”, 574-575.

[35].↑Sonenscher M., (1987). The Hatters of Eighteenth-Century France (Berkeley : University of California Press), 58.

[36].↑ Ibid., 33

[37].↑ Le Roux T., (2010), “Santés ouvrières”, 575.

[38].↑ Tenon, dans Michel Valentin, “Jacques Tenon (1724-1815) précurseur de la Médecine Sociale”, Communication présentée à la séance du 25 janvier 1975 de la Société Française d’Histoire de la Médecine, 70.

[39].↑ Le grand bol de fluide toxique est manipulé sans protection par le travailleur !

[40].↑ “Conseil hygiénique”, (1862). Le moniteur de la chapellerie, 15 (15 mai), 143.

[41].↑ Chris Heal examine le stéréotype du chapelier alcoolique qui était en partie basé sur des faits.

[42].↑ Tenon J-R., (1806). “Mémoire sur les causes de quelques maladies qui affectent les chapeliers”, Mémoires de l’Institut de France-Sciences physiques et mathématiques, Paris : Baudouin, 100-103, 107.

[43].↑ Valentin, “Jacques Tenon”, 70.

[44].↑ Ibid.

[45].↑ Le Roux T., (2010), “Santés ouvrières”, 577.

[46].↑ Gazette de santé 10 (7 mars 1776).

[47].↑ En 1778, la Society of Arts en Grande-Bretagne offrit un prix, et en 1784, l’Académie des sciences en France lança un concours pour aider les chapeliers, un prix ne fut attribué qu’en 1787 à un chapelier nommé Gosse. Heal, p. 96 et Le Roux, (2010), “Santés ouvrières”, 584.

[48].↑ Le Roux T., (2011). “L’effacement du corps de l’ouvrier. La santé au travail lors de la première industrialisation de Paris (1770‑1840)”, Le Mouvement Social, 234, 110.

[49].↑ Le chapelier qui a mis au point un équipement de protection était le fils de Gosse. Le Roux T., (2011), “L’effacement”, 112.

[50].↑ Le Roux T., (2011). Le laboratoire des pollutions industrielles, Paris 1770‑1830, (Paris : Albin Michel), 11.

[51].↑ Blanc, “How Everyday Things Make People Sick”, 3.

[52].↑ Varenkamp J.C. et al., (2003). “Mercury Contamination Chronologies from Connecticut Wetlands and Long Island Sound Sediments”, Environmental Geology, 43, 280.

[53].↑ Varenkamp J.C., (2006). “Mercury Contamination in Long Island Sound”, Chinese Journal of Geochemistry, 25 (suppl.) 236-237.

[54].↑ Guillerme A., (2007) La naissance de l’industrie à Paris.

[55].↑ Guillerme A., (2007). “Le mercure dans Paris. Usages et nuisances (1780-1830)”, Histoire Urbaine 18, n°1, 79.

[56].↑ Ibid., 94.

[57].↑ Ibid., 93.

[58].↑ Dyon S., (2013). “La Chapellerie :’a Preparatory Sketch for Service des Arts Industriels”, V&A Online Journal 5, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/research-journal/issue-no.-5-2013/la-chapellerie-a-preparatory-sketch-for-the-service-des-arts-industriels, consulté le 24 mai 2014.

[59].↑ Thomson J., (1995). Treatise on Hat-Making and Felting (Philadelphia : Henry Carey Baird, 1868), in: Suzanne Pufpaff, “Nineteenth Century Hat Maker’s and Felter’s Manuals”, Hastings, MI : Stony Lonesome Press, 111.

[60].↑ Préaud T., (1997). The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory: Alexandre Brongniart and the Triumph of Art and Industry, 1800-1847 (New York : Yale University Press), 257.

[61].↑ Le Roux T., (2011) “L’effacement”, 112, 116.

[62].↑ The Hat Makers Manual ; Containing a Full Description of Hat Making in all its Branches (London : Cowie and Strange, 1829), dans Pufpaff, “Nineteenth Century Hat Maker’s and Felter’s Manuals”, 27.

[63].↑ “Ascot Top Hats”. Communiqué de presse, 16 juin 2009.

[64].↑ Ewing E., (1981). Fur in Dress (London : B.T. Batsford), 88.

[65].↑ Carroll s’intéressait à la médecine et lut plusieurs livres sur le sujet. Plusieurs médecins n’ont pas une bonne compréhension historique de l’étendue du problème. Wedeen soutient erronément que la reconnaissance médicale de l’empoisonnement par le mercure date de 1860. Wedeen R.P., (1989), “Were the Hatters of New Jersey ‘Mad’?”, American Journal of Industrial Medicine 16, 225‑33. Dans le BMJ, H. A. Waldron soutient que le personnage du chapelier était basé sur un négociant en meubles excentrique nommé Theophilus Carter qui portait un chapeau haut-de-forme. ‘Did the Mad Hatter Have Mercury Poisoning?’, BMJ 287, n° 6409 (1983), 1961.

[66].↑ Goodacre S., (1984). Éditeur du Journal of the Lewis Carroll Society, réponse à H.A. Waldron, dans BMJ 288, n° 6413, 325.

[67].↑ “As Mad as a Hatter” Punch (4 janvier 1862), 8. L’hôpital de Bedlam ou de Bethléem était l’un des « asiles d’alliénés » les plus connus de cette période.

[68].↑ En 1863, Frank Marshall écrit une parodie interprétée à Londres intitulée “Mad as a Hatter” (“Fou comme un chapelier”), mais qui prenait place au XVIIème siècle. Partridge E., (1973), Routledge Dictionary of Historical Slang (London : Routledge).

[69].↑ Heal, “Alcohol, Madness”, 111.

[70].↑ London Metropolitan Archives, London Guildhall Corporation Coroner’s Records, 1840.

[71].↑ Chambe C., (1857). De l’empoisonnement par le nitrate acide de mercure (Strasbourg), 11.

[72].↑ Chevallier A., (1860), De L’intoxication par l’emploi du nitrate acide de mercure chez les chapeliers (Paris, Rignoux), 12. Précisément au collet des dents.

[73].↑ Dr Layet A., (1875), Hygiène des professions et des industries (Paris, Ballière), 197.

[74].↑ Heal C., (2013), “Alcohol, Madness”, 108.

[75].↑ Soit la maladie des personnes qui triaient la laine crue littéralement.

[76].↑ “An Investigation of the Shaving-Brush Industry, with Special Reference to Anthrax,” Public Health Reports 34, n°19 (1919), 994-95 ; S. Dana Hubbard, “Anthrax in Animal (Horse) Hair : The Modern Industrial and Public Health Menace”, Journal of the AMA 75, n°25 (1920), 1687-90 ; “Anthrax from Shaving Brushes,” American Journal of Public Health 15, n°5 (1925), 77.

[77].↑ Thomson J., (1868), Treatise on Hat-Making and Felting, 96, 119.

[78].↑ Lee W.R. , (1968). “ The History of the Statutory Control of Mercury Poisoning in Great Britain ”, British Journal of Industrial Medicine, vol. 25, n°1 (janvier), 52-53.

[79].↑ Ils n’ont pas été en mesure de réclamer une indemnisation en vertu du Workman’s Compensation Act jusqu’en 1906. Ibid., 57.

[80].↑ Williston S.W., (1900), “On Manufacturing Processes and Refuse,” Tenth Report Board of Health, Connecticut, 1888-9, in: George W. Rafter, Sewage Disposal in the United States (New York : D. Van Nostrand Company). L’auteur était professeur à l’université Yale.

[81].↑ Porter C., (1902). “Remarks on Felt Hat Making: Its Processes and Hygiene”, BMJ (15 février), 378.

[82].↑ Kingsbury J., (1913). Portfolio of Dermochromes, vol. II (New York : Rebman), 110.

[83].↑ Tylecote F.E., (26 octobre 1912) “Remarks on Industrial Mercurial Poisoning in Felt-Hat Makers”, The Lancet vol. 180 no. 4652, 1138-1139.

[84].↑ Porter C., (1902)“Remarks on Felt Hat Making”, 380 ; Tylecote, “Remarks on Industrial Mercurial Poisoning,” 1138.

[85].↑ Hamilton A., (1925), Industrial Poisons in the United States (New York : Macmillan), 113.

[86].↑ Rambousek J., (1913). Industrial Poisoning from Fumes, Gases and Poisons of Manufacturing Processes, trad. Thomas Legge (London : Edward Arnold), 142.

[87].↑ Buckell M. et. al., (1946). “ Chronic Mercury Poisoning”, British Journal of Industrial Medicine 3, n°2, 55.

[88].↑ Hamilton, (1937). Industrial Poisoning, 254 ; F.H. Goldman, “The Determination of Mercury in Carroted Fur”, Public Health Reports 52, n°8, 221-223.

[89].↑ Archives Atelier-Musée, sous-série 5 N : Personnel Fléchet, enveloppe n°24, en date du 30 avril 1937.

[90].↑ Science News Letter (September 7, 1946), 157.

[91].↑ “Mercurialism and Its Control in the Felt-Hat Industry”, Public Health Reports 56, n°13 (28 mars 1941), 663.

[92].↑ Lee W.R., (1968) “The History of the Statutory Control”, 59.

[93].↑ “Annual Report for 1912 of H.M. Chief Inspector of Factories”, The Lancet (19 juillet 1913), 166.

[94].↑ C’était un colorant à l’aniline. Voir BMJ (19 juin 1875), 817.

[95].↑ Précy A., (1829). Essai sur les coiffures, considérées sous le point de vue de leurs influences (Paris, Didot Jeune), 20.